| Citation: | Ranxing Cao, Waner Liang, Jia Guo, Hongyan Yang, Lili Sun, Qing Chen, Tao Yu, Sicheng Ren, Cai Lu, Guangchun Lei, Yifei Jia. 2023: Global population estimate and conservation gap analysis for the Nordmann's Greenshank (Tringa guttifer). Avian Research, 14(1): 100099. DOI: 10.1016/j.avrs.2023.100099 |

Nordmann's Greenshank (Tringa guttifer) is a globally endangered species that has received little research attention. It is threatened by rapid habitat loss, an incomplete network of protected sites, and lack of long-term data on population dynamics. Citizen science data can be combined with survey data to support population estimation and conservation gap analysis. From 2020 to 2021, Nordmann's Greenshank was surveyed in Tiaozini, Xiaoyangkou, and Dongling on the southern coast of Jiangsu Province, China, and the global population of the species was re-evaluated using the data obtained. We integrated citizen science data from eBird and the China Bird Report from 2000 to 2020 with the survey results to identify important habitats harboring over 1% of its total population, and compared this data with existing protected areas to identify gaps in its global conservation. Our survey found that Tiaozini supported at least 1194 individuals. Consequently, its global population was re-estimated to be 1500-2000. Moreover, 45 important habitats were identified based on citizen data and survey results. Although 44.4% and 50.0% of the priority sites in the world and China, respectively, are located outside protected areas, the Conservation Effectiveness Index (C) is 68.4% and 71.1%, respectively, showing that the current coverage of protected areas for this part of its range is reasonable. This study presents the most complete and recent population data to date. Tiaozini is the most important migration stopover site for Nordmann's Greenshanks. The species is under threat in terms of breeding, wintering, and stopover sites. Therefore, we suggest improving monitoring, establishing new protected sites to complete the habitat protection network, and improving the effectiveness of existing habitat protection strategies, including further developing high tide roosting sites.

The global population of waterbirds is declining rapidly, with approximately 23% of the population declining as a result of increasing threats of habitat loss and degradation due to urbanization, aquaculture expansion, and land reclamation (Kirby et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2018; Zhang and Ouyang, 2019). According to the cases of well-studied waterbird species (e.g., spoonbills, cranes, and Black-tailed Godwits Limosa limosa) (Luo et al., 2012; Jung et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2022), the establishment of protected areas has positive effects on the conservation of waterbirds (Chape et al., 2005). However, most of the threatened waterbirds in the East Asian–Australasian Flyway (EAAF) have not been well studied nor protected, with a notable lack of long-term data on population size (Wang et al., 2018) and gaps in protection networks (Xia et al., 2017). Effective waterbirds conservation depends on reliable scientific estimation of their population size. To better protect endangered waterbirds, it is essential to understand their population dynamics (Cui et al., 2014) and geographical distributions. Based on this, identifying conservation priority areas is beneficial to efficiently protect waterbirds and minimize their habitat loss (Freudenberger et al., 2013). Gap analysis is considered an effective tool for identifying protection priority areas and guiding the establishment for a complete global protection network (Rodrigues et al., 2004).

Citizen science has been collecting data on birds for 200 years (Ma et al., 2012). Further, citizen-collected data on birds are of larger spatial scales than those of other faunal groups (Chandler et al., 2017). A survey of key habitats with citizen science data will promote the accuracy of global population assessments. Citizen science data can complement institutional waterbirds monitoring data and promote multilateral cooperation between research institutions and citizen scientists (Greenwood, 2007).

The EAAF supports the highest proportions of threatened migratory waterbirds globally (Kirby, 2010; Conklin et al., 2014), but due to habitat loss and hunting (Turrin and Watts, 2016; Bellio et al., 2017; Si et al., 2018) bird populations dependent on the EAAF have declined rapidly in recent years. Nordmann's Greenshank (Tringa guttifer) is an endemic species that is representative of coastal wetland species in the EAAF, and its population is also on the decline (Birdlife International, 2016; Handono et al., 2021); moreover, it is listed as an endangered (EN) species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The breeding sites of Nordmann's Greenshank are located on Sakhalin Island and the southwest and north coasts of the Sea of Okhotsk, Russia (Zöckler et al., 2018). The Yellow Sea area of China is their key stopover site (Tong et al., 2012), and they tend to remain on the southern coast of Jiangsu for about three months during the southbound migration period (Yang et al., 2020). Due to the lack of survey data, most wintering sites of this species are not well known, except Thailand and Malaysia in Southeast Asia, which are known as the main wintering sites (Zöckler et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2020).

Unfortunately, key wintering sites of Nordmann's Greenshank in Thailand are under threat of gradual degradation due to anthropogenic activities (Tantipisanuh et al., 2016). The important stopover sites in the Yellow Sea have decreased by two-thirds in the last 50 years (Murray and Fuller, 2015; Melville et al., 2016), mainly due to reclamation projects and the expansion of the invasive species, Smooth Cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), resulting in a significant loss of coastal wetlands in southern Jiangsu (Jackson et al., 2021).

Not only is the current knowledge of the distribution of Nordmann's Greenshank incomplete, but there is also a lack of research on its migratory dynamics and feeding habits (Urfi, 2015). According to the First Conservation Status Review of migratory waterbirds for the East Asian–Australasian Flyway Partnership (EAAFP CSR1) (Wetlands International, 2020), the global population of Nordmann's Greenshank was estimated to be approximately 900–1200. However, in 2013, approximately 1200 Nordmann's Greenshanks were recorded in Jiangsu Province (Anon, 2013), indicating that its population has been previously underestimated.

To improve the understanding of the population size and geographical distribution of threatened waterbirds, and better protect Nordmann's Greenshank and similar species, this study employed a combination of field investigation, citizen science data, and applied Geographic Information System (GIS) techniques to (1) reassess the global population size, (2) identify globally important stopover and wintering sites, and (3) identify gaps in the conservation network of Nordmann's Greenshank.

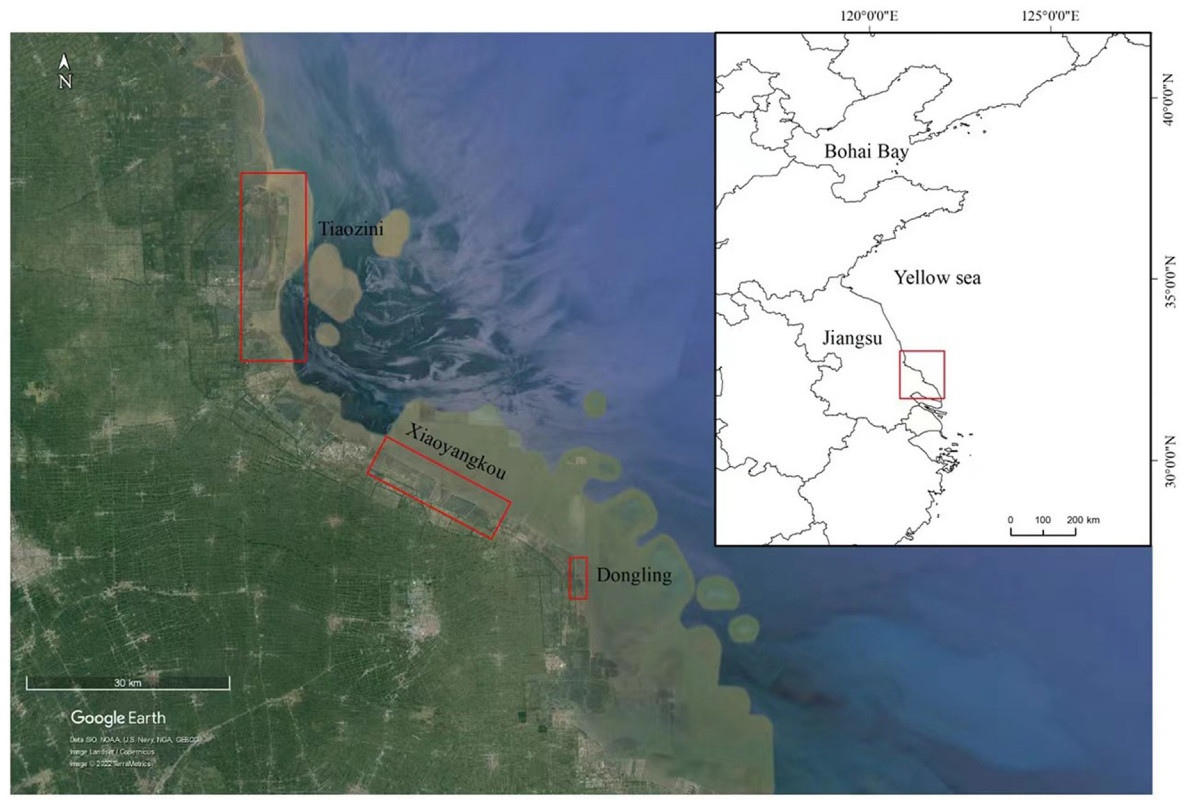

Jiangsu Province is located in the coastal area of the Yellow Sea of China, which is located in the EAAF. Its coastal tidal flats are important parts of the wetland system in the Yellow Sea and Bohai Sea areas of China. Previous studies have shown that Jiangsu is an important stopover site for Nordmann's Greenshank. Most of the individuals of the species regularly appear in the southern coastal areas of Jiangsu (Yang et al., 2020), among which Tiaozini (32.79° N, 120.97° E), Xiaoyangkou (32.56° N, 121.06° E), and Dongling (32.39° N, 121.43° E) are the important areas, and they were therefore selected as the survey areas (Fig. 1). The annual average temperature of the Tiaozini wetland in Dongtai County is 15 ℃. The coastline is approximately 18 km in length and approximately 3 km in width (East–West). The region mainly comprises coastal natural tidal flats and artificial inland fish ponds (Gao et al., 2021). The survey area in Tiaozini consists of two high tide roosting sites. One of the sites named ‘720 mu’ was transformed from fish ponds in 2020 by artificially controlling the water level, and the other is named ‘10,000 mu’ which is the uncultivated land with water area after coastal reclamation. Rudong County, under the effect of both a subtropical and maritime monsoon climate, with an annual average temperature of 15 ℃, comprises a coastline approximately 106 km in length, and a tidal flat with an area of 6.93 × 104 ha (Xu and Pu, 2014). Xiaoyangkou and Dongling are components of the Rudong tidal flats. Xiaoyangkou carried out a wetland restoration project to remove Spartina alterniflora from the tidal flats in 2019, and some of the cleaned tidal flats can be used by Nordmann's Greenshank as a high tide roosting site. But after that, there is no artificial management of tidal flat. Dongling has no high tide roosting site, and the tidal flat is completely submerged by the tide during the spring tide.

A simultaneous survey of waterbirds was conducted in the three areas during the autumn migration (August–October) in 2020 and 2021 and the spring migration (April–May) in 2021. Due to a lack of workforce and resources, no surveys were conducted in Dongling during the spring migration in 2021. The surveys were conducted at spring tide twice a month. Overall, 24 surveys were conducted in Tiaozini, 8 in Xiaoyangkou and 4 in Dongling.

Surveys were adopted according to the conditions of different census areas. Bird surveys were conducted at high tide roosting sites at the highest tide level (i.e., all mudflats were submerged) at Xiaoyangkou and Tiaozini, where high tide roosting sites were available. No high tide roosting sites were identified in the Dongling area; therefore, the investigators arrived at the dike of the sea 2–3 h before the highest tide. Depending on the visibility conditions during the surveys, counting was initiated when the tide was 300–500 m from the bank. In the bird surveys, three or four experienced researchers were assigned to lead each survey area, and 8 × binoculars (Swarovski ATS 80 HD) and 20–60 × spotting scopes (Swarovski EL 42) were used to identify and record the number of Nordmann's Greenshanks.

Based on the results of the surveys, using the CSR evaluation methods, the population of Nordmann's Greenshank was reasonably re-estimated (Wetlands International, 2020).

The records of birdwatchers in eBird (www.ebird.org) and the China Bird Report (http://www.birdreport.cn) from 2000 to 2020 were collected and analyzed. A single record with Nordmann's Greenshank population larger than 10 (1% of the species population) recorded at a site was used for analysis, and other records at the same site were discarded. We define the site as an area (1) with a consistent natural geography, without physical barriers, and (2) within 20 km from the coast, which is the maximum activity diameter for foraging and roosting for shorebirds (Jackson et al., 2020).

By integrating field survey data and citizen data, the coordinates of the presence of Nordmann's Greenshank were compiled. The coordinates were put into Google Earth Pro for analysis. According to the local terrain and habitat conditions, records were filtered according to our definition of sites by visual verification. The sites harboring 1% or more of the previously estimated global population of Nordmann's Greenshank (according to EAAFP CSR1) were selected and considered as key habitats.

To determine the relative priority of sites we used the Importance Index (I) (Xia et al., 2017) (Eq. (1)). It can indicate the importance and conservation value of a site, with higher values indicating a higher conservation priority.

| I=∑si=1ni/N | (1) |

In this equation, ni denotes the population of the Nordmann's Greenshank at the ith survey site, s means the number of sites in a region, and N denotes the flyway population of Nordmann's Greenshank, according to EAAFP CSR1 (Wetlands International, 2020).

The distribution of key habitats for Nordmann's Greenshank was compared with the global distribution of protected areas provided by the World Database of Protected Areas (WDPA) to identify unprotected key habitats. Manual visual checks were carried out to correct data bias in the WDPA. Unprotected key habitats were identified as conservation gaps.

The Conservation Effectiveness Index (C) (Xia et al., 2020) was used to quantify the relative degree of protected area coverage (Eq. (2)). The higher the C value, the better the protection of the main protected areas.

|

C=Cp/Ct |

(2) |

where Cp denotes the sum of the importance index of the sites under effective protection in certain range with many sites, and Ct denotes the sum of the importance index of all the sites in the flyway.

We selected the data of Nordmann's Greenshank in the overwintering period from November 2018 to March 2019 and November 2019 to March 2020 in eBird, and the records with the largest number of Nordmann's Greenshanks at each site were selected. The selected records were compiled together to calculate the population of Nordmann's Greenshank in the wintering sites.

At the high tide roosting sites at Tiaozini in September and October 2020 and 2021, more than 1000 Nordmann's Greenshanks were recorded continuously. The Tiaozini site supported the highest number of Nordmann's Greenshanks among the three study areas, followed by Dongling and Xiaoyangkou (Table 1). The number of individuals observed at each site exceeded 1% of the global population; thus, they can be considered as important migratory stopover sites. Survey results from 2020 to 2021 showed no significant inter-annual changes in population size at both Tiaozini and Xiaoyangkou, while Dongling showed a significant increase in population size.

| Survey time | Survey site | ||

| Tiaozini | Xiaoyangkou | Dongling | |

| 2020.08 | 11 | 3 | – |

| 2020.09 | 1150a | – | 33 |

| 2020.10 | 838a | 3 | 5 |

| 2021.04 | 16 | 1 | – |

| 2021.05 | 51 | 1 | – |

| 2021.08 | 515a | 10 | – |

| 2021.09 | 1194a | 19 | 100a |

| 2021.10 | 1077a | 36 | 127a |

| a Indicates more than 10% of the population size. | |||

Over the survey period, Tiaozini and Dongling were each found to support approximately 10% of the total Nordmann's Greenshank population. Tiaozini is particularly important, with the maximum value for each year of more than 1100 in 2020 and 2021. Based on the survey results, we reassessed the global population of Nordmann's Greenshank as ranging from 1500 to 2000.

Analyzing data from eBird and the China Bird Report from 2000 to 2020 (Fig. 2), a total of 28 sites in China were identified with more than 1% of the global population of Nordmann's Greenshank. These sites were coastal mudflats, with five sites hosting more than 10% of the global population, mainly in Shandong, Hebei, Jiangsu. The top three sites with the most individuals reported were all located in Jiangsu Province, namely in Tiaozini, Xiaoyangkou, and Dongling. The Importance Index (I) value of Tiaozini is greater than 1, which indicates that the site plays an important role for Nordmann's Greenshank. Besides China, 15 countries had records of Nordmann's Greenshank, and 17 sites in 7 countries reported Nordmann's Greenshank exceeding 1% of the global population size. Among these sites, two hosted more than 10% of the global population and were located in Thailand. However, no data were recorded for Nordmann's Greenshank breeding sites at Sakhalin Island in eastern Russia and the southwestern and northern coasts of the Sea of Okhotsk.

A total of 20 conservation gaps were identified out of 45 key habitats for Nordmann's Greenshank (Fig. 2). These conservation gaps accounted for 44.4% of the global key habitats and 50.0% of China's key habitats. Due to the lack of data on breeding sites, their conservation status could not be determined. The conservation gap of the Nordmann's Greenshank population exceeding 10% was 42.9% for sites around the world and 40.0% areas for sites in China.

We found C index for sites globally had an average value of 68.4%. China has a slightly higher C index value of 71.1%. The Importance Index (I) of Thailand (0.398) is second only to China (2.751). Thailand's C index is 67.6%, and its protection level is slightly lower than the global average (68.4%).

In the winter of 2018–2019, 370 Nordmann's Greenshank individuals were recorded, of which 270 were recorded in Thailand, accounting for 73.0% of the wintering population. In the winter of 2019–2020, 387 Nordmann's Greenshank individuals were recorded, of which 330 were recorded in Thailand, accounting for 85.3% of the wintering population.

The CSR estimated the number of Nordmann's Greenshank at 900–1200, based on expert opinion. It has updated the data for EAAFP CSR 1 (http://wpe.wetlands.org/explore/3009/568). The IUCN assessed the global population of Nordmann's Greenshanks to comprise of 600–1300 individuals, based on the observation of 1200 Nordmann's Greenshanks in Jiangsu by the Spoon-billed Sandpiper Task Force (Tong et al., 2014). In this study, 1194 Nordmann's Greenshanks were observed during a single survey in the Tiaozini, Jiangsu Province. We surveyed two high tide roosting sites during spring tide during one day, on September 22, 2021, then combined the data. According to this data and the CSR, we estimated the global population of Nordmann's Greenshank to be between 1500 and 2000 individuals. To the best of our knowledge, this study reports the latest and most reasonable global population assessment for the species.

Our result differs from previous population size assessments, possibly because in this study we obtained the latest reliable data from continuous surveys during the migration season at southern Jiangsu over two consecutive years. The artificial high tide roosting sites in Tiaozini were established in 2020. At high tide, Nordmann's Greenshanks flock together at the high tide roosting sites, thus creating favorable conditions for surveys with better data accuracy. Reference to multi-sourced citizen science data will be more beneficial for a reasonable and accurate assessment of the Nordmann's Greenshank population.

This study covered three important tidal flats along the southern coast of Jiangsu Province, but not the Lianyungang area of Jiangsu Province, which also supports more than 1% of the Nordmann's Greenshank population (Choi et al., 2020). Citizen science data show that in coastal areas of China, except Jiangsu, there are multiple other sites supporting over 1% of the Nordmann's Greenshank population. Future research should be conducted in coordination with the China Coastal Waterbird Census and the Yellow Sea–Bohai Region Coordinated Waterbird Survey in these areas to further explore the population and migration dynamics of Nordmann's Greenshank.

In July 2019, Tiaozini became a part of World Heritage coastal wetland site called Migratory Bird Sanctuaries along the Coast of Yellow Sea–Bohai Gulf of China (Phase I) (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1606). Studies have shown that as shorebirds frequently return to their favored stopover sites (Hua et al., 2015), any habitat destruction at wintering, stopover, and breeding sites would have a serious impact on shorebird population dynamics and species survival (Moores et al., 2016; Ma, 2017). Since then, protection efforts in the region have gradually increased, which aid in protecting Nordmann's Greenshank, such as the establishment of artificial high tide roosting sites. As the stopover site of almost the entire population of Nordmann's Greenshank, it is crucial to maintain and further strengthen the conservation actions at Tiaozoni.

Coastal wetlands in southern Jiangsu not only support almost all of the Nordmann's Greenshank populations, but also the threatened Spoon-billed Sandpiper (Calidris pygmaea), Great Knot (Calidris tenuirostris), and Far Eastern Curlew (Numenius madagascariensis), according to the IUCN (Tong et al., 2012). These regions support more than 20 species of shorebirds by hosting over 1% of their respective populations (Bai et al., 2015). The area of the coastal tidal flats in Tiaozini has decreased due to the invasion of S. alterniflora (Liu, 2018), causing fluctuating changes in landscape diversity and reducing the dominance of the original landscape types (Wang et al., 2019). In addition to the reduction of tidal flat area, habitat quality has also been affected (Wan et al., 2009). The invasion of S. alterniflora affected the species composition of benthic biodiversity (Qiu et al., 2010), influencing the food quality of the mudflats, which in turn impacted shorebird community composition by affecting the food webs (Li et al., 2009). The invasion of S. alterniflora is more widespread within the reserve than outside it (Ren et al., 2021). Therefore, S. alterniflora control in protected areas is critical for protecting shorebirds such as Nordmann's Greenshank.

Outside China, in addition to the threat of habitat loss in the Yellow Sea, reclamation activities in South Korea have also aggravated the loss of stopover sites of Nordmann's Greenshank (Moores, 2007). Moreover, breeding sites in eastern Russia were negatively impacted by Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) grazing (BirdLife International, 2012), which aggravated the breeding pressure on Nordmann's Greenshank. Also, the lack of citizen participation in breedings sites calls for more attention. Meanwhile, in the wintering areas of Southeast Asia, such as Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, and other countries, poaching and economic development pose a threat to the Nordmann's Greenshank population (Urfi, 2015).

Human disturbance is one of the main threats to shorebirds (Zang et al., 2019), which decreases the habitat quality and affects their foraging efficiency (Rogers et al., 2006b). Some shorebirds rely on non-protected areas, which requires proper management to reduce human disturbance (Szabo et al., 2016; Studds et al., 2017). The important stopovers in the Yellow Sea and wintering sites of Nordmann's Greenshank have been disturbed by human activities to varying degrees (Hua et al., 2015; Putra et al., 2015; Urfi, 2015). The important conservation approach should be to implement proper management of human disturbance to these sites.

Overall, the protection rate of key habitats within the migratory range of Nordmann's Greenshank is low. The protection rate in sites with more than 10% of the population globally increased by 1.59% compared to those with more than 1%. Excluding China, wintering grounds in Thailand host more than 10% of the population, but similar to the pattern in China, the country has a relatively high proportion of conservation gaps. The gaps in the conservation network of Nordmann's Greenshank reached 44.4% globally and 50% in China, which is similar to the average conservation gaps (58.46%) of other coastal waterbirds in Chinese mainland (Duan et al., 2021).

The introduction of a Conservation Effectiveness Index (C) (Xia et al., 2020) is useful to reflect the role of habitat importance ranking in conservation gaps. This method is more effective in assessing the conservation status of a species. The higher the C value, the more the population of Nordmann's Greenshank in a particular protected area is conserved. The global C value of Nordmann's Greenshank is 68.4%, and that of China is 71.1%. The rate of gaps in China is slightly higher than the world level, but the C value is higher than the global average, which shows that there are more Nordmann's Greenshank populations in China and that they are protected.

Among them, the Importance Index (I) of Tiaozini area in China is the highest. The high C value in China indicates that existing conservation areas protect the important habitat of Nordmann's Greenshank, i.e., Tiaozini. Protecting priority areas with a high I value can effectively improve conservation effectiveness. Establishing new protected areas or expanding existing ones in Thailand, and giving priority to covering priority conservation areas with high I values, could further increase conservation effectiveness.

The ecological importance of Tiaozini, Xiaoyangkou, and Dongling along the southern Jiangsu coast is increasing (Duan et al., 2019), but Dongling has not been established as a protected site, thus constituting a significant gap in the conservation network. Thailand and Malaysia (Singh et al., 2021; Yong et al., 2022) also have significant conservation gaps and low C value, where the wintering population of Nordmann's Greenshank is not effectively protected and its population maintenance is still under significant pressure. The conservation level of the species at its overwintering areas is lower than the average conservation level of waterbirds in the EAAF. Therefore, the conservation efforts in overwintering areas need to be considerably improved. Establishing protected areas at the conservation gaps to protect mudflats can reduce the rate of mudflat loss. However, some mudflats within protected areas are still being lost (Murray and Fuller, 2015). Therefore, reasonable protected area planning should be carried out for important habitats of Nordmann's Greenshank population, and protection and management within protected areas should be strengthened.

Due to land use changes and invasive alien species in coastal areas, the number of high tide roosting sites that can be used by shorebirds is gradually decreasing (Hua et al., 2015). Some artificial wetlands can also be used by shorebirds as high tide roosting sites (Masero, 2003), but these wetlands are often highly disturbed by human interference, and require appropriate artificial management before they can be effectively utilized by shorebirds (Golet et al., 2018). The lack of high tide roosting sites affects waterbirds' choice of foraging sites, increases energy consumption to foraging sites, forces them to spend more time searching for high tide roosting sites at high tide, and increases foraging risk during migration (Dias et al., 2006; Rogers et al., 2006a). The simultaneous survey in Tiaozini during two consecutive years found that most Nordmann's Greenshanks rested at the Tiaozini '720 mu' high tide roosting site during the high tide.

The '720 mu' high tide roosting site was built in 2020 to protect waterbirds in Tiaozini, which is an important stopover site for Nordmann's Greenshank (Yang et al., 2020). Stopover site plays an important role in the long-distance migration of birds (Bamford et al., 2008). The observation of the largest population of Nordmann's Greenshank in the world at this site is probably due to the availability of suitable high tide roosting sites, which reduce energy expenditure thus ensure energy replenishment at the stopover sites. High tide roosts also allow a more accurate survey of both population number and general waterbird community composition because Nordmann's Greenshank was more concentrated at high tide roosts during spring tide. The high tide roosting sites provide habitat and feeding areas during high tide for most plovers that are not adapted to foraging in deep water (Choi et al., 2014; Green et al., 2015), in addition to providing nesting sites for other shorebirds (Rocha et al., 2016). The artificial construction of high tide roosting sites can provide suitable environments for Nordmann's Greenshank and other shorebirds, as well as improve conservation efficacy in protected areas.

In this study, we re-estimated the global population of Nordmann's Greenshank to be more than 1500. However, according to eBird data, a total of 387 individuals were recorded in wintering areas such as Thailand and Malaysia in 2019–2020, and 370 were recorded in wintering areas in 2018–2019. The population number recorded in wintering areas is smaller than that re-estimated in this paper. This indicates there are still undiscovered wintering grounds. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen the population monitoring in wintering areas. Timely and effective monitoring is essential to effective species conservation (Hertzog et al., 2021).

Citizen science has a greater chance of discovering new wintering sites (Amano et al., 2016) and filling the research gap on the distribution of the wintering sites of Nordmann's Greenshank. A comprehensive understanding of the species is important to estimate the population and identify key distribution areas, and then implement effective conservation measures, for example, managing high tide roosting sites (Bai et al., 2018), strengthening socio-ecological management practices (Campos-Silva et al., 2021), restoring habitats (Yong et al., 2022), and identifying conservation gaps (Xia et al., 2020).

Because of the significance of the stopover sites, the mudflats need to be protected dynamically during specific periods when Nordmann's Greenshank migrates south and north. Human activities on the mudflats should be strictly controlled during the period in which Nordmann's Greenshank and other threaten or endangered species use the mudflats, and the mudflats can be appropriately opened during non-occupancy periods. Nature reserves should be designated at existing conservation gaps, and the establishment of reserves in areas that host 10% of Nordmann's Greenshank population and that have high I values should be prioritized to promote the security of the species' resting, foraging, and overwintering sites.

The quality and size of mudflats at important stopover sites should be monitored, and invasive alien plants must be regularly removed to improve habitat quality and maintain the suitability of mudflat habitats for foraging. We suggest strengthening management of those areas with more than 10% population and existing high tide roosting sites. Regular water level management measures should be undertaken to improve the availability of artificial high tide roosting sites. Almost all shorebird species in EAAF rely on Tiaozini in Jiangsu when migrating, so it is very important to protect this stopover.

The results of this paper can provide significant support for the government to develop conservation planning and management strategies, and implement species conservation actions. It promotes the protection of the gap areas mentioned in this paper in future conservation efforts. Our findings can provide a basis of population estimation for the East Asian–Australasian Flyway Partnership (EAAFP), as well as relevant conservation advice.

Ranxing Cao: data analysis and article writing. Waner Liang: article review and edit, bird data collection. Jia Guo: article review and edit, drawing the map of study sites, bird data collection. Hongyan Yang: article review and edit, bird data collection. Lili Sun: bird data collection. Qing Chen: bird data collection. Tao Yu: bird data collection. Sicheng Ren: article review and edit. Yifei Jia: article writing-review and edit, project administration. Cai Lu: article review and edit. Guangchun Lei: conceptualization. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Jiangsu Dongtai coastal economic zone approved the bird survey. This research was performed by experienced researchers and abided by the laws and regulations of the place where the work was conducted.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We acknowledge the support for our field research from Jiangsu Dongtai coastal economic zone, Jiangsu Province, China. The manuscript was improved with help from Yan Zhou. We thank Dongming Li for help during the waterbird survey. We wish to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing. We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and editor for their constructive inputs that helped improve the manuscript.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avrs.2023.100099.

|

Anon, A., 2013. New hope for two of the world's most endangered shorebirds. Bird. Watch. 98, 278-290.

|

|

Bamford, M., Watkins, D., Bancroft, W., Tischler, G., Wahl, J., 2008. Migratory Shorebirds of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway: Population Estimates and Internationally Important sites. Wetlands International Oceania, Canberra.

|

|

Choi, C.Y., Li, J., Xue, W.J., 2020. China Coastal Waterbird Census Report (Jan. 2012-Dec. 2019). Hong Kong Bird Watching Society, Hong Kong.

|

|

Conklin, J., Verkuil, Y.I., Smith, B.R., 2014. Prioritizing Migratory Shorebirds for Conservation Action on the East Asian-Australasian Flyway. World Wildlife Fund, Hong Kong.

|

|

Duan, H.L., Yu, X.B., Shi, J.B., Lei, J.Y., Xia, S.X., 2021. Identifying conservation priority sites and gaps for the waterbirds habitat along coastal wetlands in mainland China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 41, 9574-9580. (in Chinese).

|

|

Gao, S., Liu, W., Zhang, S., Yi, J.F., Wang, Z., 2021. Diversity of wintering waterbirds in Tiaozini wetland of Dongtai and Rudong wetland, Jiangsu Province. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 37, 1176-1182. (in Chinese).

|

|

Kirby, J., 2010. Review 2: Review of current knowledge of bird flyways, principal knowledge gaps and conservation priorities. Flyway Working Group Reviews, CMS Scientific Council.

|

|

Liu, M.Y., 2018. Remote sensing analysis of Spartina alterniflora in the coastal areas of China during 1990 to 2015. Doctoral Thesis. Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. (in Chinese).

|

|

Ma, Z.J., 2017. The importance of habitat protection to bird protection. Bull. Biol. 52, 6-8. (in Chinese).

|

|

Masero, J.A., 2003. Assessing alternative anthropogenic habitats for conserving waterbirds: Salinas as buffer areas against the impact of natural habitat loss for shorebirds. Biodivers. Conserv. 6, 1157.

|

|

Moores, N., 2007. South Korea's shorebirds: a review of abundance, distribution, threats and conservation status. Stilt 50, 62-72.

|

|

Putra, C.A., Hikmatullah, D., Prawiradilaga, D.M., Harris, J.B., 2015. Surveys at Bagan Percut, Sumatra, reveal its international importance to, migratory shorebirds and breeding herons. KUKILA 2, 46-59.

|

|

Qiu, L., Liu, J.E., Chen, J.Q., Wang, G.X., Chang, Q., 2010. Impacts of Spartina alterniflora invasion on the macrobenthos communities of Jiangsu's coastal wetlands. Mar. Sci. 34, 50-55 (in Chinese).

|

|

Rogers, D.I., Battley, P.F., Piersma, T., Van, G.J.A., Rogers, K.G., 2006a. High-tide habitat choice: insights from modelling roost selection by shorebirds around a tropical bay. Anim. Behav. 3, 563-575.

|

|

Tong, M., Zhang, L., Jing, L., Zckler, C., Clark, N.A., 2012. The critical importance of the Rudong mudflats, Jiangsu Province, China in the annual cycle of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper Calidris pygmeus. Wader Study Group Bull. 119, 74-77.

|

|

Turrin, C., Watts, B.D., 2016. Sustainable mortality limits for migratory shorebird populations within the East Asian-Australian Flyway. Stilt 68, 2-17.

|

|

Urfi, A.J., 2015. Foraging ecology and conservation of waders along coast of India: need for detailed studies. Wader Study 122, 153-159.

|

|

Xia, S., Yu, X., Millington, S., Liu, Y., Jia, Y., Wang, L., et al., 2017. Identifying priority sites and gaps for the conservation of migratory waterbirds in China’s coastal wetlands. Biol. Conserv. 210, 72-82.

|

|

Xu, Y., Pu, L.J., 2014. The variation of land use pattern in tidal flat reclamation zones in Jiangsu coastal area: a case study of Rudong County of Jiangsu Province. J. Nat. Resour. 29, 643-652. (in Chinese).

|

|

Zöckler, C., Li, D., Chowdhury, S.U., Iqbal, M., Chen, X., 2018. Winter distribution, habitat and feeding behaviour of Nordmann's Greenshank Tringa guttifer. Wader Study 125, 7-14.

|

| Survey time | Survey site | ||

| Tiaozini | Xiaoyangkou | Dongling | |

| 2020.08 | 11 | 3 | – |

| 2020.09 | 1150a | – | 33 |

| 2020.10 | 838a | 3 | 5 |

| 2021.04 | 16 | 1 | – |

| 2021.05 | 51 | 1 | – |

| 2021.08 | 515a | 10 | – |

| 2021.09 | 1194a | 19 | 100a |

| 2021.10 | 1077a | 36 | 127a |

| a Indicates more than 10% of the population size. | |||