| Citation: | Tong ZHANG, Ming MA, Peng DING, Feng XU, Paul J. BUZZARD. 2012: Status and behavior of the Black-necked Crane (Grus nigricollis) in the Altun Mountain Reserve, Xinjiang. Avian Research, 3(3): 199-205. DOI: 10.5122/cbirds.2012.0021 |

The Black-necked Crane (Grus nigricollis) is an endemic species of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, with its population in Xinjiang largely found in the Kunlun and Altun mountain regions. A survey of the distribution, population dynamics, flock size and behavior was conducted in Altun Mountain National Natural Reserve from September to November 2011. We investigated the size and distribution of its population in this area with a sample spot survey and by direct counting. We found Black-necked Cranes on the wetlands of Wuzunxiaoer, Yusup Aleksei, Yaziquan, Qimantag, Tula Ranch and elsewhere, where we recorded 126 individual birds of the species in Yixiekepati (37° 15'-37°23'N, 90°11'-90°20'E, elevation 3903 m), the largest population we have observed in this area. In the reserve, the population consists of about 180-200 birds. Combined with previous records, we conclude that more than 260 Black-necked Cranes live in Xinjiang. Cranes gathered conspicuously in the middle of October where the highest number of birds appeared on 29 October. All of the cranes had migrated out of this area by 6 November. Time budgets and diurnal behavior rhythms of Blacknecked Cranes were observed in the Yixiekepati wetland at daylight (from 06:00 to 18:00). Foraging was the most prevalent type of behavior during the autumn period, accounting for 58.9% of the diurnal time budget, followed by preening (13.2%), vigilance (9.5%), walking (8.2%), flying (3.5%), resting (3.4%), chirping (2.7%) and other types of behavior (0.6%).

The Black-necked Crane (Grus nigricollis) is one of the most important protected animals in China as well as in the world and the only crane species living entirely on high plateaux. The Black-necked Crane is found at elevations of 2950–4900 m in the breeding season and between 1900 and 3950 m in the winter (Bishop, 1996). In China it is mainly distributed on the Qinghai-Tibetan and Yunnan-Guizhou plateaux (Li, 1997; Ma et al., 2000; Ma, 2011). A small part of their breeding range also extends into India, Bhutan and Nepal (Li et al., 2005; Li and Li, 2005).

The Black-necked Crane is evaluated as vulnerable (VU) according to the endangered categories of the IUCN, because it has a single small population that is declining due to the loss and degradation of wetlands, as well as changing agricultural practices in both its breeding and wintering grounds (BirdLife International, 2009). According to research of its migration patterns, Black-necked cranes are divided into a western, a central and an eastern population (Li and Bishop, 1999). Those that breed in Xinjiang at the northern edge of the Tibetan Plateau belong to the western population, the least studied of the three populations.

Since the 1970s, the Black-necked Crane has been studied primarily in Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan, Qinghai, Gansu and Tibet (Ran et al., 1999; Li and Yang, 2003; Kong et al., 2008; Tsamchue et al., 2008). Black-necked cranes have rarely been studied in Xinjiang and the few earlier studies are incomplete and likely inaccurate (Gao, 1987; Zhang and Zhang, 1991; Tian, 1999).

The Altun Mountain Nature Reserve is the most important breeding ground for Black-necked Cranes in Xinjiang (Ma et al., 2011). This remote reserve is one of the best-preserved plateau ecosystems in the world and one of the breeding areas for the Black-necked Crane in Xinjiang. In this study, we review the status of the cranes. We used direct observations to study their behavior, assessed the threats to the cranes and attempted to obtain more information essential for conservation of the species.

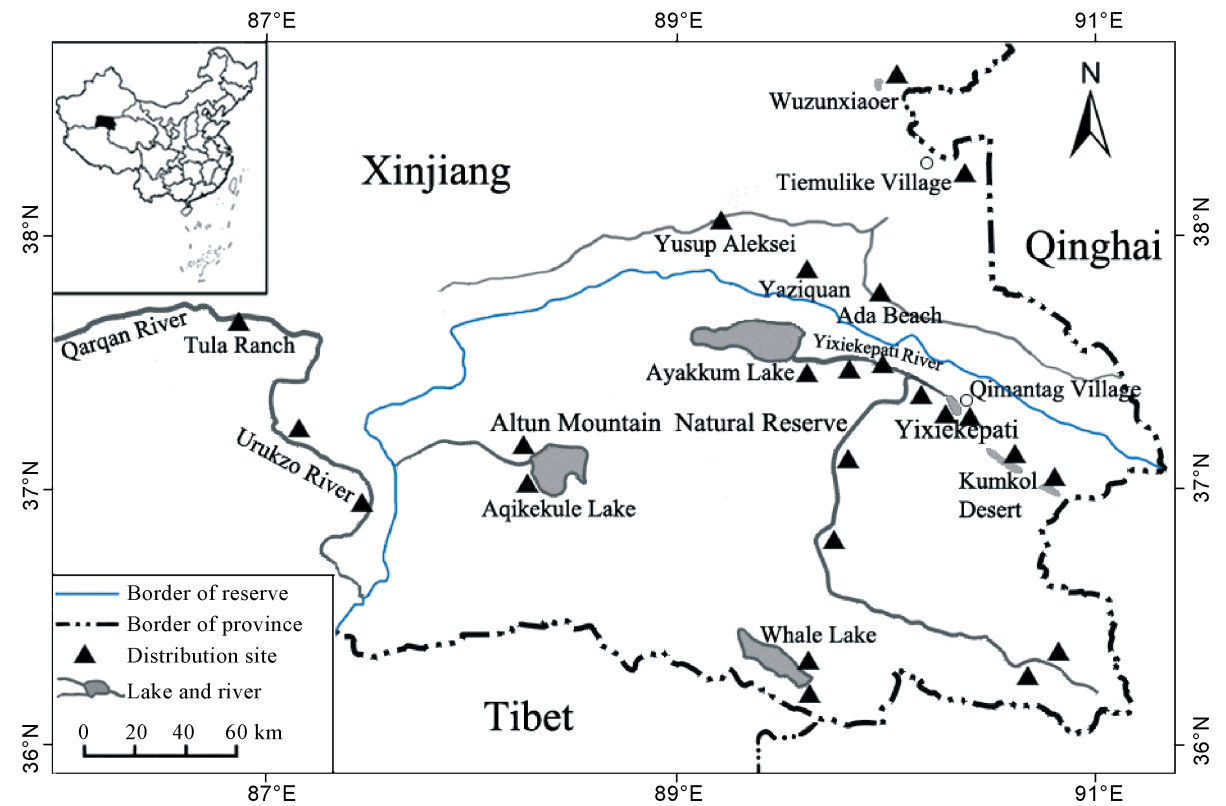

The Altun Mountain National Nature Reserve at 45000 km2 is one of the largest plateau reserves. It is located in Ruoqiang County, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China (36°00′–37°49′N, 87°10′–91°18′E) and extends to the northwestern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, north of Tibet and west of Qinghai (Fig. 1). This reserve is characterized by its high location with an average elevation of 4500 m; the highest point is Muztagh Mountain (6973 m) and the lowest area is Ayakkum Lake (3876 m). The climate of the area is dry and cold. Precipitation is rare and sparse and frequently falls as snow or sleet, even in the summer (Achuff and Petocz, 1988). However, the landscape is mostly flat and plants are abundant around lakes and rivers. There are three large lakes in the reserve, together accounting for approximately 1220 km2 of surface area, i.e., Ayakkum Lake, Aqikekule Lake and Whale Lake. There are also many other small lakes and rivers. Plants are short and small, many of them belonging to alpine cushion vegetations, such as Ceratoides compacta, Poa arjinsansis, Puccinellia arjinshanensis, Carex kunlunshansis, C. atrofusca, C. orbicularis, C. microglochin, Myriophyllum spicatum and others. It is a good breeding area for the Black-necked Crane.

From September to November of 2011, we used a sample spot survey and direct counts in the Altun Reserve as well as around the reserve to determine the distribution and number of cranes. Cranes live mainly in wetlands near lakes and rivers, hence wetlands near the water were our main observation spots.

From 20 September to 6 November, we used continuous recording and scan sampling at 10 min intervals (Altmann, 1974) to document Black-necked Crane behavior at the Yixiekepati wetland (37°18′N, 90°20′E). We observed cranes from 06:00 to 18:00 for a total of 216 hours and documented 21120 behavioral events with telescopes (Carl Zeiss, Diascope 85, 20–60; Minox BV 10 × 42 BR). The types of behavior of the Black-necked Crane was divided into eight categories: foraging (searching and handling food, drinking), preening (preening with beak or claw, shaking and washing), vigilance (stretching the head upwards, looking around while standing or working), walking, flying, resting (sleeping while lying or standing), chirping and other types of behavior (excretion, antagonism, dancing). We also counted some other water birds.

We interviewed local herders, miners and reserve staff to confirm crane habitats and assessed potential habitats within the reserve. The interviews also touched on information about the current status of cranes, including the impact of domestic livestock, illegal poaching and predators. Such information is critical for devising suitable methods for crane protection.

Through observation and analysis, a total of 220–260 Black-necked Cranes were found in Altun Nature Reserve and surrounding areas (Fig. 1, Table 1). Of these, 180–200 individual birds live in the reserve, primarily around Ayakkum, Aqikekule and Whale lakes. Dozens of crane families, totaling more than 130 cranes, were found beside the Yixiekepati River. About ten cranes lived in small lakes within the Kumkol Desert, the highest desert of the world (Fig. 1). Although we most often found Black-necked cranes in wetlands around rivers and lakes, we repeatedly found that the cranes were active far away from the water in alpine meadows and even at edges of the desert. About 42–60 cranes were scattered around the reserve in a variety of places such as Tiemulike Village, Wuzunxiaoer, Yusup Aleksei and Qarqan river basins, Yaziquan, Ada Beach and Tula Ranch (Fig. 1, Table 1).

| Location | Number of birds |

| Qimantag Village | 180–200 |

| Tiemulike Village | 8–10 |

| Wuzunxiaoer | 4–6 |

| Kazakbeyti | 4–6 |

| Yusup Aleksei | 4–6 |

| Qarqan River Basin | 4–6 |

| Yaziquan | 4–6 |

| Tula Ranch | 6–10 |

| Urukzo River Basin | 4–6 |

| Ada Beach | 2–4 |

| Total | 220–260 |

A total of 158 cranes belonging to 68 families were observed at the Yixiekepati wetland in the autumn. Family group sizes were from one to four birds (Fig. 2). Cranes were rarely alone; our records show only four occasions where we found a single bird, accounting for 5.9% of the families (n = 68). Forty-one families consisted of pairs of cranes, accounting for 60.3% of the 68 families, i.e., the largest proportion. The second largest configuration is families with three members, of which we observed 20 families, accounting for 29.4% of the total number of families. The remaing three families belonged to four member households and accounted for 4.4% of all families. During our study period, 26 juveniles were observed in the Black-necked Crane population, representing 16.5% of all 158 cranes.

We observed changes in flock size of the Black-necked Crane at the Yixiekepati wetland from September to November 2011 (Fig. 3). Before October families moved around; in rare cases, some families walked together and gathered for a short time. The cranes started to gather into one large flock in October. At the start, only about 10 cranes came together, but by mid-October 40–60 cranes had gathered together. The number of the cranes in the flock continued to rise in the following days, but on 19 October, most cranes in this flock left because of grazing sheep. The cranes did not return until the sheep left two days later. The flock size increased to more than 60 birds by late October, with the highest number of 126 individual birds on 29 October 2011.

Black-necked cranes started migration on 29 October 2011 and nearly 79% of the birds flew away the following three days. There were less than 30 cranes left by November 2011. We found only three individual birds (one family) on 4–5 November and no cranes remained on 6 November 2011.

Time budgets and diurnal behavior rhythms

During the migration season, the predominant type of behavior of Black-necked cranes was foraging, accounting for 58.9% of their time budgets. The second most prevalent type of behavior was preening, about 13.2% of the time budgets. Meanwhile, vigilance (9.5%) and walking (8.2%) also made up important parts of their daylight activities. The other four types of behavior, flying, resting, chirping and others were rare at 3.5%, 3.4%, 2.7% and 0.6% of time budgets respectively.

Some behavior types of cranes showed rhythms during the daytime (Fig. 4). Foraging increased during the day with cranes foraging least often (24.5%) in the early morning (06:00–07:00) and most often (75.1%–81.5%) in the evening (16:00–18:00). Conversely, vigilance showed a decreasing trend peaking early in the morning and gradually decreasing during the day. Neither preening nor walking behavior showed a clear daily rhythm, but both showed a slight decline at nightfall. The peak time of flying occurred during the hours from 06:00–07:00 and 14:00–16:00 when cranes flew between foraging and resting places. The same situation also occurred in their resting behavior. The peak time of resting appeared before flying into foraging places in the morning and after flying into resting places in the evening. The peak time of chirping occurred from 06:00–07:00 after the cranes had flown to their feeding places. Other special types of behavior, such as fluttering wings, leg stretching, jumping and antagonism were rare and did not have daily rhythms.

The Black-necked Crane is one of the most important, rare and protected birds both in China and abroad. They are monotypic species and are without subspecies differentiation (Wang et al., 2006). According to migration research, the population of this crane in China is divided into three populations, i.e., a western, a central and an eastern population (Li and Bishop, 1999). The cranes living in Xinjiang belong to the western and least-studied of the three populations. A few earlier studies are incomplete and contain some mistakes (Gao, 1987; Zhang and Zhang, 1991; Tian, 1999). For example, according to the data collected by the State Forestry Administration, there are about 1200 Black-necked cranes in Xinjiang, based on a total distribution area of 367998 km2 with a density of 0.1884 individual birds per 100 km2 (National Forestry Bureau, 2009). The distribution area estimated is too large, however, accounting for 23% of the total Xinjiang area and the data source is unknown (Ma et al., 2011). Based on our surveys and analysis, we estimated the population size of the Black-necked Crane to be about 180–200 in the Altun Mountain Nature Reserve and more than 260 birds in Xinjiang. Most are found in the Kunlun and Karakorum mountains.

The amount of time a bird allocates to different activities may approximately reflect its energy budget (Weathers et al., 1984; Ricklefs, 1996). The time budget is adaptive and information about it is useful for evaluating the relationships of species to their environments (Lu and Zheng, 2009). In autumn, the cranes need to store extra energy in preparation for migration. As a result, they spent most of their daily activity time in foraging (> 58%). Affected by physiological activities and environmental factors for cranes, the rhythm of various types of behavior varied during the day and the time spent feeding increased during the day. When flying into a feeding spot each morning, the cranes spent relatively much more time being vigilant. As time went on, they became familiar with the surrounding environment and their level of vigilance decreased; consequently, foraging could increase. In addition, crane group size may have been a factor because time used for foraging may increase due to reduced scanning for predators when animals live in groups (Beauchamp, 1998). Flying behavior had peaks in the morning and evening when cranes flew between foraging and resting places, but the cranes also flew during the daytime to practice for migration.

Natural selection favors those animals that can organize their activities to a proper schedule in response to local environments (Cuthill and Houston, 1997). By the end of October, snowy weather had increased and lakes were becoming frozen at Altun. Also by the end of October the cranes were in larger and larger groups and the aggregation of cranes began to migrate to the south. Some reports say that the western populations of the Black-necked Cranes may migrate to Tibet or Bhutan (Wu et al., 1993; Yan, 2006), but this has not been confirmed for the Xinjiang cranes. We observed that the cranes flew in a southeast direction, but future satellite tracking of cranes is necessary to clarify routes and stopovers to enhance Black-necked Crane conservation.

From October to March, wintering populations of Black-necked Cranes live in the south of Tibet (Cang et al., 1994). However, from November to March some flocks overwinter in Yunnan (Gao et al., 2007). Cranes reaching Xinjiang in early April and living there to November are adapted to the migration time of the Yunnan population. Maybe Black-necked Cranes at Altun Mountain belong to one of the populations of Yunnan, migrating every year between Yunnan and Xinjiang.

According to our field work and preliminary interviews, we found that because of environmental changes, livestock husbandry, mining and increasing eco-tourism activities, the population of Black-necked cranes has been faced with some threats recently. Increasing livestock husbandry, mining and eco-tourism activities potentially threaten the Black-necked Crane with poaching and egg collection. In response to these threats, the protection and management work of the reserve administration needs to be strengthened and herders, miners, tourists and reserve staff all need to be educated about the protected status of cranes. At the same time, a long-term monitoring program should be established to strengthen the conservation and management of Black-necked Cranes in the reserve. The number of juveniles that we observed (16.5%), out of a total of 158, can be used as a baseline to monitor future fecundity and population trends.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31272291, 30970340), the Hong Kong Bird Watching Society China Conservation Fund and the Management Bureau of Altun Mountain Natural Reserve. We sincerely thank Weidong Li, Xiang Zhang, Huibin Zhang, Donghua Xu, Ming Liu, Huan Li, Ying Chen, Mardan Turghan, Tuson Sawut, Zhaosong Liu, Aishanjiang and Feng Gao and others.

|

Achuff P, Petocz R. 1988. Preliminary Resource Inventory of the Arjin Mountains Nature Reserve, Xinjiang, People's Republic of China. World Wide Fund for Nature, Gland, Switzerland.

|

|

Bishop MA. 1996. Black-necked Crane (Grus nigricollis). In: Meine C, Archibald G (eds) The Cranes: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, pp 184-193.

|

|

Cang QZM, Gu BY, Bishop MA. 1994. The number of wintering Black-necked Crane in Tibet. Tibet Sci Technol, 3: 12-13. (in Chinese)

|

|

Cuthill IC, Houston AI, 1997. Managing time and energy. In: Krebs JR, Davies NB (eds) Behavioural Ecology: An Evolutionary Approach (4th edn). Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, pp 97-120.

|

|

Gao LB, Qian FW, Yang XJ, Wu HQ, Li FS. 2007. Satellite tracking on the migratory routes of wintering Black-necked Cranes at Dashanbao in Yunnan. Zool Res, 28(4): 353-361. (in Chinese)

|

|

Gao XY. 1987. The birds in East Kunlun-Altun mountains regions. Arid Zone Res, 4: 1-10. (in Chinese)

|

|

Kong DJ, Yang XJ, Zhong XY, Dao MB, Zhu Y. 2008. Diurnal time budget and behavior rhythm of wintering Black-necked Crane (Grus nigricollis) at Dashanbao in Yunnan. Zool Res, 2: 195-202. (in Chinese)

|

|

Li F S, Bishop M A. 1999. Ecology and conservation of Black-necked cranes Grus nigricollis. In: Adams NJ, Slotow RH (eds) Proc 22 Int Ornithol Congr, Durban. BirdLife South Africa, Johannesburg, pp 2533-2543.

|

|

Li FS, Yang F. 2003. Population numbers and distribution of Black-necked Cranes (Grus nigricollis) in the Yungui Gaoyuan Plateau. Chin J Zool, 3: 43-46. (in Chinese)

|

|

Li FS, Yang XJ, Yang F. 2005. Status and Conservation of Black-necked Cranes on the Yunnan and Guizhou Plateau, People's Republic of China. Yunnan National Publishing House, Kunming, pp 44-56. (in Chinese)

|

|

Li LX. 1997. Population ecology and endangered categories evaluation of the Black-necked crane (Grus nigricollus). Chin Biodivers, 2: 84-89. (in Chinese)

|

|

Li ZM, Li FS. 2005. Black-necked Crane Study. Shanghai Technological and Educational Press, Shanghai. (in Chinese)

|

|

Lu X, Zheng GM. 2009. Time budgets of Tibetan eared pheasants during the non-breeding season in an alpine scrub habitat. Curr Zool, 3: 193-199.

|

|

Ma M. 2011. A checklist on the Distribution of the Birds in Xinjiang. Science Press, Beijing, pp 39-40. (in Chinese)

|

|

Ma M, Li WD, Zhang HB, Zhang X, Yuan GY, Chen Y, Yuan L, Ding P, Zhang Y, Cheng Y, Sagen GL. 2011. Distribution and population state of Black-necked crane Grus nigricollus in Lop Nur and Kunlun Mts., Southern Xinjiang. Chin J Zool, 3: 64-68. (in Chinese)

|

|

Ma ZJ, Zhang ZW, Chen JK. 2000. Effects of climate change on the distribution of cranes in China. Glob Environ Res, 4: 231-237. (in Chinese)

|

|

National Forestry Bureau. 2009. Resource Survey on the Key Animals in China. China Forestry Publishing House, Beijing, pp197-206.

|

|

Ran JH, Liu SY, Zeng ZY, Shao KQ, Lin Q, Zhang M. 1999. The population and distribution of Black-necked Cranes (Grus nigricollis) in Xiaman Nature Reserve in Sichuan. Chin J Appl Environ Biol, 1: 40-44. (in Chinese)

|

|

Ricklefs RE. 1996. Avian energetics, ecology, and evolution. In: Carey C (ed) Avian Energetics. Chapman and Hall, New York, pp 1-30.

|

|

Tian FL. 1999. Plateau bird-black-necked crane. Environ Protect Xinjiang, 4: 63. (in Chinese)

|

|

Tsamchue D, Yang L, Li JC, Yangjaen D. 2008. Current status of conservation and research on Black-necked Cranes. Sichuan J Zool, 3: 449-453.

|

|

Wang QS, Ma M, Gao YR. 2006. Fauna Sinica Aves. Vol. 5. Gruiformes, Charadriiformes and Lariformes. Science Press, Beijing, pp 48-52. (in Chinese)

|

|

Weathers WW, Buttemer AM, Hayworth AM, Nagy K. 1984. An evaluation of time budget estimates of daily energy expenditure in birds. Auk, 101: 459-472.

|

|

Wu ZK, Li ZM, Wang YH, Jiang YM, Li RX, Li DH, Zhou ZJ, Li LX. 1993. Migration of Black-necked Crane in China. Acta Zool Sin, 1: 105-106. (in Chinese)

|

|

Yan S. 2006. Migration of Black-necked Crane. Forest Humankind, 11: 56-59. (in Chinese)

|

|

Zhang F, Zhang HB. 1991. Preliminary report of Black-necked Crane in Yixiekepati lakeside, Altun Mountains. Yunnan Geogr Environ Res, 2: 92-93. (in Chinese)

|

| Location | Number of birds |

| Qimantag Village | 180–200 |

| Tiemulike Village | 8–10 |

| Wuzunxiaoer | 4–6 |

| Kazakbeyti | 4–6 |

| Yusup Aleksei | 4–6 |

| Qarqan River Basin | 4–6 |

| Yaziquan | 4–6 |

| Tula Ranch | 6–10 |

| Urukzo River Basin | 4–6 |

| Ada Beach | 2–4 |

| Total | 220–260 |