| Citation: | Xin LU. 2012: Summer-autumn habitat use by Galliformes in a primary forest, southeastern Tibet. Avian Research, 3(2): 113-117. DOI: 10.5122/cbirds.2012.0014 |

Habitat use by Galliformes in an ornithologically unexplored region, a forest area in south-eastern Tibet, was investigated during the summer and autumn periods of 1995. A total of seven species were recorded, most of which preferred habitats on south-facing slopes and avoided those on north-facing slopes where conditions were relatively humid. A hybrid population of White (Crossoptilon crossoptilon) versus Tibetan Eared-pheasants (C. harmani) was predominant among the Galliforme community, followed by Blood Pheasants (Ithaginis cruentus) and Chinese Grouse (Bonasa sewerzowi). A further investigation in 2001 showed that on account of little human activity in the distant primary forests, the birds suffered less of a threat from hunting and habitat disturbance.

With complex geographical and climatic conditions, the forest areas in southeastern Tibet are home to many species of Galliformes. Previous fauna surveys in the region, either by foreigners during earlier times (Bailey, 1914; Battye, 1935; Ludlow and Kinnear, 1944) or by Chinese ornithologists since the 1960s (Cheng et al., 1983), only provided general information about the occurrence of Galliforme species. To understand the conservation status of these species in primary forests, we should have more quantitative data on habitat use and population abundance. Moreover, Galliforme species are susceptible to habitat change and are often treated as indicators of ecosystem health (Fuller et al., 2000; Fuller and Garson 2000; Storch, 2000). Data from areas with original ecosystems may provide a baseline for assessing the degree of habitat degradation in contrast to these highly human-disturbed areas.

From May to October 1995, I investigated the habitat use of Galliformes in the upper Yigong Zangbu River, an area never explored by biologists. A further survey aimed at assessing the conservation status of the taxa in the area was made in May 2001.

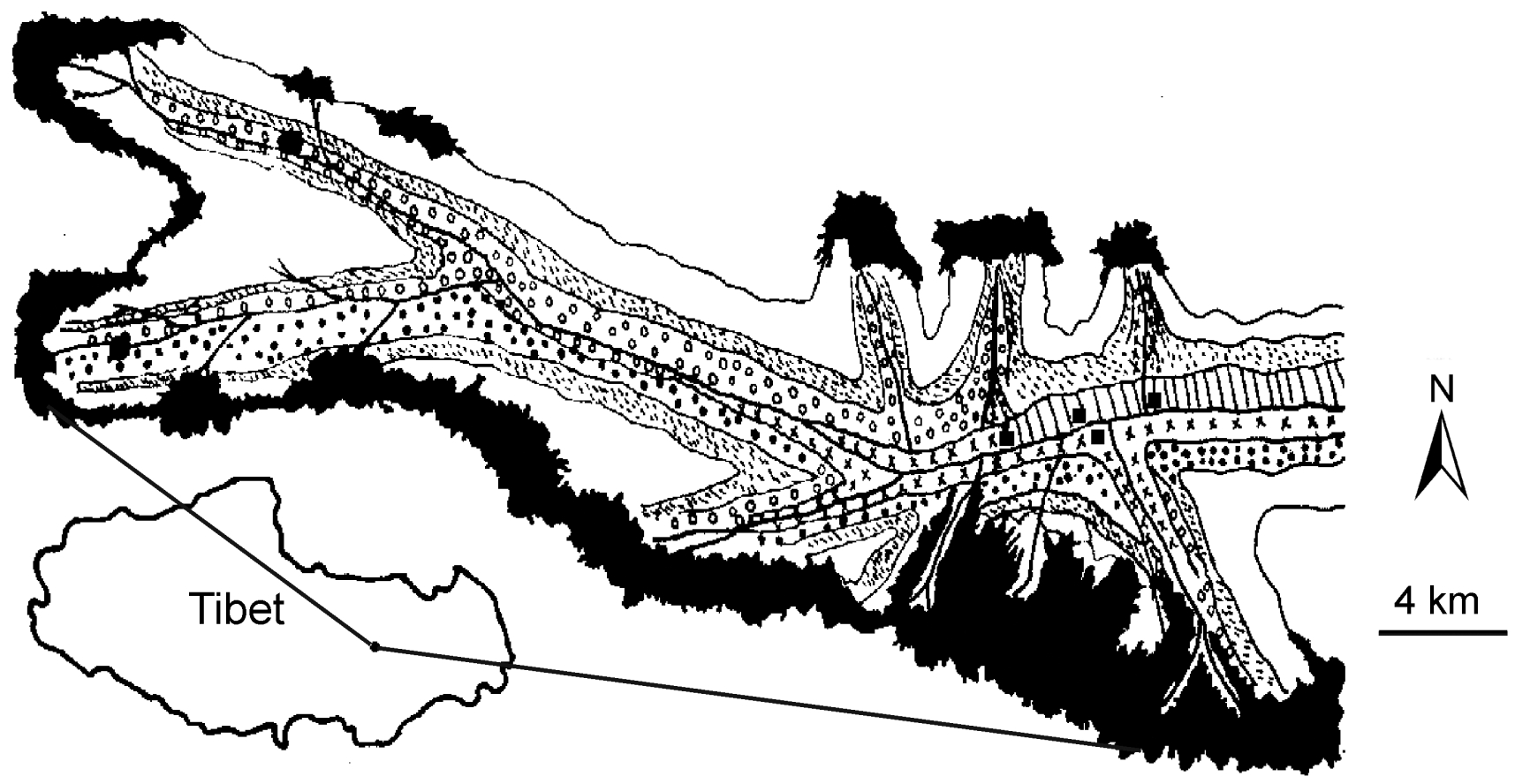

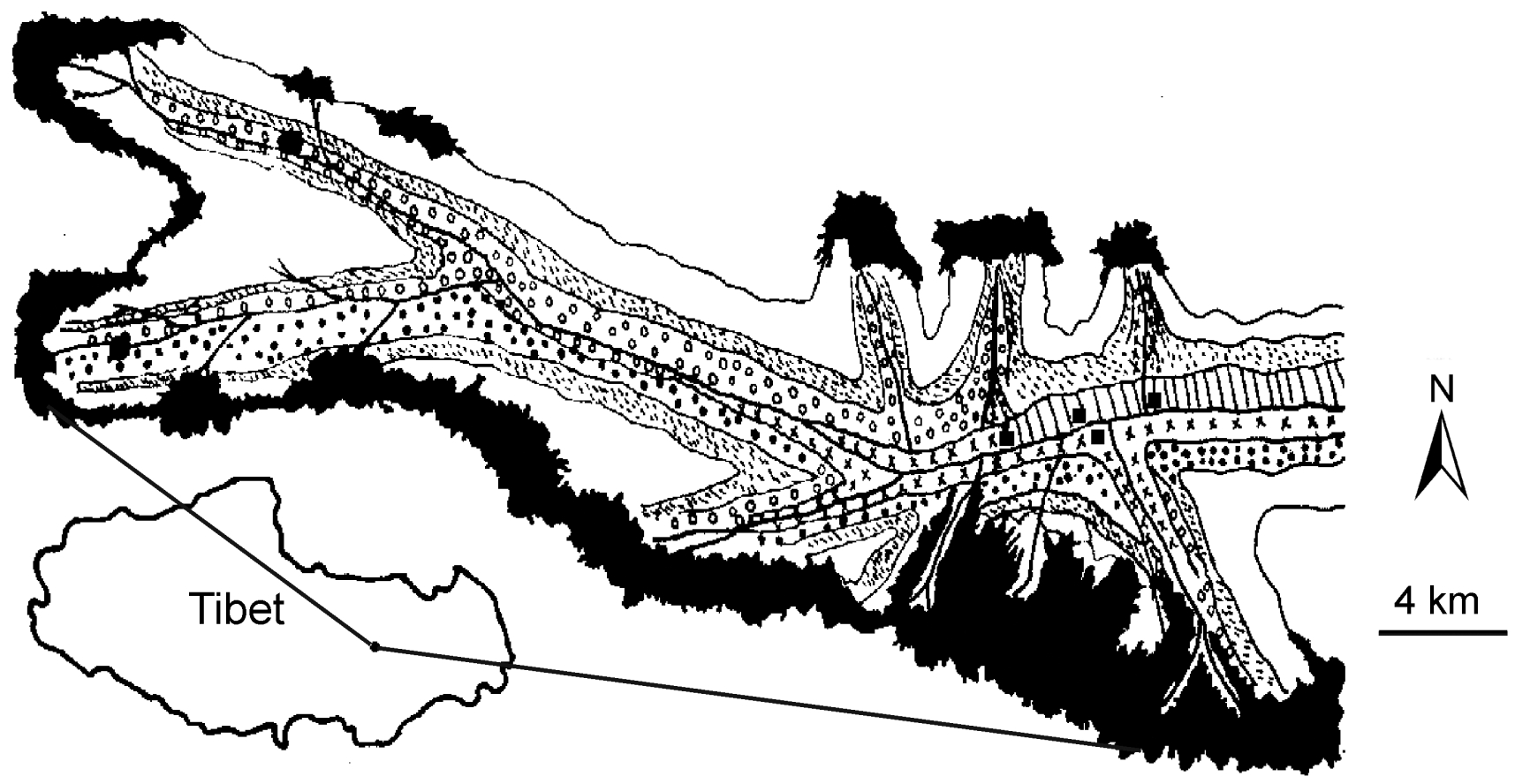

Fieldwork was carried out in the Sawang area (93°39′E, 32°24′N; Fig. 1), in Jiali county, southeastern Tibet, from May to October in 1995. Topographically, the study area is characterized by high mountains and deep canyons, with elevations ranging from 3700 to 6870 m, where most valley bottoms are less than 100 m wide. My survey area covered 32 km of the main valley and 14 km of three branches of the valley (Fig. 1). The vegetation is still original and varies vertically. On north-facing slopes < 4300 m in elevation, plant communities in the forest are dominated by Halfour spruce (Picea likiangensis) and between 4300–4800 m, by forests and scrubs of Rhododendron spp.; on south-facing slopes, between 3700–4300 m, the forest is dominated by Hollyleaf-like oak (Quercus aquifolioldes) between 4200–4700 m, by Tibetan juniper (Sabina tibetica) and at elevations > 4700 m, by alpine scrubs and meadows.

Along the entire valley of 50 km, there are only five Tibetan villages, with a very low population density (one person per 100 km2). Farmland is restricted to the bottom of the mountains. The villagers cut the oaks near the foot of the mountains for firewood, resulting in secondary scrub oak forests.

Because the birds are shy in dense cover, I had few opportunities to catch sight of them. However, I found that feathers, fallen from their plumage, could survive for at least one month and were easy to identify in the field and distinguishable among species. The detection rate of feathers of each species in a defined habitat should be positively related with the number of birds and the time they spent in their habitat. Thus, encounter rates of molted feather samples were used as indicators of the relative abundance of Galliformes. The methodology of feather-counting was described by Lu and Zheng (2001). When collecting feather samples along the transects, I also noted individual birds, their flock size and membership. The data on individual sightings were provided in contrast to the results of feather-counting. I compared the flock size of each Galliforme species during the nesting period (late May to early July) to that in the chick-rearing period (mid-July to mid-October).

All of seven species of Galliformes in the study area were found on south-facing slopes and only two species, the Chinese Grouse (Bonasa sewerzowi) and the Blood Pheasant (Ithaginis cruentus) also appeared on north-facing slopes (Table 1). A hybrid of the White Eared-pheasant (Crossoptilon crossoptilon) × the Tibetan Eared-pheasant (C. harmani) was the most predominant component of the Galliforme community, followed by Blood Pheasants and Chinese Grouse. These three species were relatively well adapted to the various types of vegetation in the area. Two other forest-dependent species, the Snow Partridge (Lerwa lerwa) and the Pheasant Grouse (Tetraophasis obscurus), were limited to the upper part of the forests with relatively low population densities, while a third species, the Crimson-bellied Tragopan (Tragopan temminckii) was only rarely sighted. Two meadow-dependent species, the Tibetan Snow Cock (Tetraogallus tibetanus) and the Tibetan Partridge (Perdix hodgsoniae), were relatively uncommon.

| Habitat | Elevation (m) | Survey time (h) | Chinese Grouse | Snow Partridge | Tibetan Snow Cock | Pheasant Grouse | Tibetan Partridge | Blood Pheasant | Crimson-bellied Tragopan | Hybrid Eared-pheasant |

| Farmland | 3700−3800 | 46.0 | (0.04) | |||||||

| South-facing slopes | ||||||||||

| Secondary oak shrubs | 3700−3900 | 39.6 | 0.05 (0.03) | 0.81 (0.15) | ||||||

| Oak forest | 3800−4300 | 82.2 | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.02 (0.01) | 3.21 (0.34) | ||||

| Shrub-meadow above tree line | 4300−4500 | 19.5 | 0.92 | |||||||

| Juniper forests | 4200−4700 | 62.0 | 0.70 (0.13) | 0.03 (0.03) | 1.00 (1.00) | 0.03 (0.02) | 1.69 (0.27) | |||

| Shrub-meadows above tree line | 4600−4900 | 25.5 | (0.04) | (0.04) | 0.75 (0.24) | |||||

| North-facing slopes | ||||||||||

| Spruce forests | 3700−4300 | 16.6 | 0.12 (0.12) | 0.18 (0.18) | ||||||

| Rhododendron | 4300−4800 | 8.5 | 0.12 | |||||||

| Shrub-meadows above tree line | 4600−4900 | 7.0 | ||||||||

The following provides further information about each species.

The Chinese Grouse: This survey discovered a new distribution of the species, which extends its range from 98°40′ to 93°39′E. In the survey area, often 2–5 birds (3.4 ± 0.3, n = 11) were encountered in their preferred habitat with streams and dense scrub, sometimes in small open plots in the forest, feeding or dusting. If suddenly disturbed, the birds fly up to nearby trees.

The Snow Partridge: In late June, three groups with five, five and six birds respectively were flushed from a juniper woodland close to the tree line, where their dusting sites were located. In late July, two birds were found in a scrub-grassland above the tree line.

The Tibetan Snow Cock: Because of limited time of investigation in its preferred habitat, i.e., high-elevation meadows with rocks, I only saw one group of seven birds. One young bird, caught, weighted 0.53 kg, suggesting that the date of egg-laying of this bird was early April.

The Pheasant Grouse: This bird limited its activities to the upper part of the forest dominated by oak but never moved out of the forest into the scrub-grassland above the tree line. If disturbed by dogs, this bird flew up to the top of trees. Its microhabitats consisted often of rocks and streams. Dusting sites beside a path visited by the birds were found at least three times.

The Tibetan Partridge: Despite considerable efforts in investigating this species in the alpine scrub-meadows, believed suitable for this bird, I did not manage to find a single bird there. Only one pair was continuously seen at the foot of the mountains from June through July.

The Blood Pheasant: The birds occurred in various habitats but their densities on south-facing slopes were higher than on north-facing slopes. They preferred microhabitats close to streams. Usually two birds (46.5%) (2.0 ± 0.3, ranging from 1–4, n = 11) remained together during the breeding season. I found in late September that these birds and Hybrid Eared-pheasants used the same dusting hollows. In winter, according to the villagers, flocks are formed of more than 10 individual birds, appearing at lower elevations.

The Crimson-bellied Tragopan: Only two single birds were found in an oak woodland and a dusting site in the juniper forest.

The Hybrid Eared-pheasant: This bird has the largest population among the Galliformes in the area and appeared in various habitats on south-facing slopes, with oak forests as its most preferred habitat. During the nesting period (May to July), flock size varied between 1 to 7 birds (2.9 ± 0.3, n = 43) and then increased (7.0 ± 1.0, 2–15, n = 14) during the brood-rearing period (August to October).

My results showed that the Galliforme species in the study area tended to avoid coniferous forests dominated by Balfour spruce, an environment widely encountered on the eastern Qinghai-Tibet plateau and preferred by many species of Galliformes (Cheng et al., 1978; Johnsgard, 1999). The reason is thought to be that the climate in the woodland is so humid that ground-dwellers have difficulties in breeding and foraging (Lu and Zheng, 2001).

Before the 1980s, rifles were available to local people. It is generally known that game animals, including Galliformes, were frequently killed during that period. In the mid 1990's, the Firearm Law of the People's Republic of China was issued, forbidding anybody to own and keep any kind of gun privately. As a result, pressure from hunting of wildlife has declined considerably. However, trapping, especially by people from outside Tibet, has not been entirely prohibited, causing a certain loss of Galliformes. Oak-cutting in nearby villages has led to the emergence of second scrub oak forests, not suitable to Galliformes. To encourage local people to use firewood in more effective ways (for example by promoting more efficient stoves), is one means of reducing the loss of oak forests.

However, overall, because of low population densities, poor communication and less developed economies, as well as protection by local religious and government policies, Galliformes in the region have been facing relatively fewer threats. But it should be kept in mind that developing local economies and improved communication will inevitably pose a threat to wildlife. Therefore, development plans for unexplored areas should be carefully made, because once loss of biodiversity, derived from a long-term evolutionary trend, reestablishment is almost impossible.

I suggest for government agencies to establish a nature reserve in the region. This will prevent large-scale landscape use in the future and also provide a foundation for enhancing public conservation awareness. To aid conservation, further studies on the biology and ecology of the Galliformes are needed.

I would like to thank Duojicipei and his family for accommodation in the area. I am grateful to Bingyuan Gu, Soulong Ciren and Cangjue Zhuoma for their assistance in the survey. The field survey was supported by the Tibetan Bureau of Science and Technology, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 39800016) and the Tibet Important Bird Area Survey Programme organized by BirdLife International.

|

Battye RKM. 1935. Notes on some birds observed between Yatung and Gyantse, Tibet. J Bombay Nat Hist Soc, 38: 406–408.

|

|

Cheng TH, Tan YK, Lu TC, Tang CZ, Bao GJ, Li FL. 1978. Fauna of China, Aves, Vol. IV: Galliformes. Science Press, Beijing.

|

|

Cheng ZX, Li DH, Wang ZX, Wang ZY, Jiang ZH, Lu TC. 1983. The Avifauna of Tibet. Science Press, Beijing.

|

|

Fuller R, Carroll JP, McGowan PJK. 2000. Partridges, Quails, Francolins, Snowcocks, Guineafowl, and Turkeys: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan 2000–2004. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK and the World Pheasant Association, Reading, UK.

|

|

Fuller R, Garson PJ. 2000. Pheasants: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan 2000–2004. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK and the World Pheasant Association, Reading, UK.

|

|

Johnsgard PA. 1999. The Pheasants of the World. 2nd ed. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

|

|

Ludlow F, Kinnear NB. 1944. The birds of southeastern Tibet. Ibis, 86: 348–389.

|

|

Storch I. 2000. Grouse: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan 2000–2004. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK and the World Pheasant Association, Reading, UK.

|

| Habitat | Elevation (m) | Survey time (h) | Chinese Grouse | Snow Partridge | Tibetan Snow Cock | Pheasant Grouse | Tibetan Partridge | Blood Pheasant | Crimson-bellied Tragopan | Hybrid Eared-pheasant |

| Farmland | 3700−3800 | 46.0 | (0.04) | |||||||

| South-facing slopes | ||||||||||

| Secondary oak shrubs | 3700−3900 | 39.6 | 0.05 (0.03) | 0.81 (0.15) | ||||||

| Oak forest | 3800−4300 | 82.2 | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.02 (0.01) | 3.21 (0.34) | ||||

| Shrub-meadow above tree line | 4300−4500 | 19.5 | 0.92 | |||||||

| Juniper forests | 4200−4700 | 62.0 | 0.70 (0.13) | 0.03 (0.03) | 1.00 (1.00) | 0.03 (0.02) | 1.69 (0.27) | |||

| Shrub-meadows above tree line | 4600−4900 | 25.5 | (0.04) | (0.04) | 0.75 (0.24) | |||||

| North-facing slopes | ||||||||||

| Spruce forests | 3700−4300 | 16.6 | 0.12 (0.12) | 0.18 (0.18) | ||||||

| Rhododendron | 4300−4800 | 8.5 | 0.12 | |||||||

| Shrub-meadows above tree line | 4600−4900 | 7.0 | ||||||||