| Citation: | Fenliang Kuang, Wei Wu, David Li, Chris J. Hassell, Grace Maglio, Kar-Sin K. Leung, Jonathan T. Coleman, Chuyu Cheng, Pavel S. Tomkovich, Zhijun Ma. 2022: Detecting the non-breeding region and migration route of Whimbrels (Numenius phaeopus rogachevae) in the East Asian–Australasian Flyway. Avian Research, 13(1): 100011. DOI: 10.1016/j.avrs.2022.100011 |

Determining the migration routes and connections of migratory birds at the population level helps clarify intraspecific differences in migration. Five subspecies have been recognized in the Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus) in Eurasia. Ssp. rogachevae is the most recently described subspecies. It breeds in Central Siberia, while its non-breeding region and migration routes are still unclear. We tracked the migration of Eurasian Whimbrels captured at three non-breeding sites (Moreton Bay in east coast of Australia, Roebuck Bay in Northwest Australia and Sungei Buloh Wetland in Singapore) and two migration stopover sites (Chongming Dongtan and Mai Po Wetland in China). We determined the breeding sites and inferred the subspecies of the tagged birds in the East Asian – Australasian Flyway (EAAF) based on the known breeding distribution of each subspecies. Of the 30 tagged birds, 6 and 21 birds bred in the breeding range of ssp. rogachevae and variegatus, respectively; one bred in the presumed transition area between the breeding range of ssp. phaeopus and rogachevae, and two bred in the region between the breeding range of ssp. rogachevae and variegatus. The birds that bred in the ssp. rogachevae breeding range spent their non-breeding season in the northern Sumatra, Singapore, East Java and Northwest Australia and mainly stopped over along China's coasts during migration. None of our birds bred in the exclusive breeding range of the phaeopus subspecies. Previous studies have predicted that rogachevae whimbrels migrate along the Central Asian Flyway and spend the non-breeding season in West India and East Africa. We found that at least some rogachevae whimbrels migrate along the EAAF and spend the non-breeding season in Southeast Asia and Australia. The ssp. phaeopus is at best sparsely distributed in the EAAF in the west region, or possibly does not occur at all.

Anthropogenic activities have modified almost every environment in the world. Land-use change, exotic species, and climate change are the main causes of biodiversity loss worldwide (Sala et al., 2000). Biodiversity loss is not only manifested at the species level but also at the level of interactions (Valiente-Banuet et al., 2015). While the loss of ecological interactions, which often get less noticed than species loss, in many cases precedes the local extinction of interacting species (Valiente-Banuet et al., 2015). Consequently, interaction loss has very relevant functional consequences at the community level as interactions — and particularly mutualistic ones — play a major role in maintaining and generating biodiversity. Among the ample spectrum of ecological relationships, plant-pollinator interactions play a key role in plant reproduction, influencing plant regeneration processes and population persistence (Jordano, 2000; Ollerton et al., 2011). In this regard, hummingbirds, one of the most efficient pollinators as compared with other pollinator groups (e.g., Betts et al., 2015; Medel et al., 2018) can be severely impacted. Currently ca. 10% of 366 species are considered globally threatened and 60% are in current decline (Leimberger et al., 2022).

One of the major peculiarities of hummingbirds is their high dependence on flower nectar, which allows them to maintain high metabolic rates associated with stationary flight and dynamic foraging patterns. This dependence has resulted in a remarkable trait-matching between bill length and corolla length in most biogeographical regions, with exception of Caribbean Islands (Dalsgaard et al., 2021). Despite some criticisms on the idea of pollination syndrome (e.g., Waser et al., 1996; Petanidou et al., 2008), recent quantitative reviews provide support to the syndrome idea (e.g., Rosas-Guerrero et al., 2014; Dellinger, 2020). Notoriously, most hummingbird-visited plants have a well-defined suit of floral traits such as red flowers, diurnal anthesis, absence of floral fragrance, abundant nectar, long and rigid floral tubes, and zygomorphic symmetry (Faegri and van der Pijl, 1979; see review in Fenster et al., 2004). This dependence makes hummingbirds and the plants on which they feed upon particularly susceptible to climate change (Fontúrbel et al., 2021). For instance, Sonne et al. (2022) analyzed the way future climate change may cause direct extinctions (i.e., climate-driven extinctions), and coextinctions, understood as extinctions attributable to the extinction of mutualistic partners. Their study concluded that climate-driven extinctions are expected to have the lowest impact in Andean plant-hummingbird communities, being North America and lowland South America the most sensitive communities to climate change. Regarding coextinctions, their study indicates that the impact of climate change will depend on the structure of plant-hummingbird interaction networks. Unfortunately, data on South America excluded information from Chile, as few studies on plant-pollinator networks have been performed in this country, and plant-hummingbird communities are relatively depauperate in comparison to those from tropical and subtropical environments. Therefore, a review of the hummingbirds inhabiting Chile and the plant resources on which they feed upon seems necessary and timely. The motivation to perform this review is to systematize the available information regarding the flowering plants visited by each hummingbird species, emphasizing the characteristics of the available information, that is, noting whether it consists of casual observations (OBSC), presence-absence data of interactions in a community context (Qualitative or Binary Matrix, MATB), rate data, or presented as frequencies of visitation in a community context (MATC). This information is shown in Appendix Table S1 (available online as Appendix A. Supplementary data).

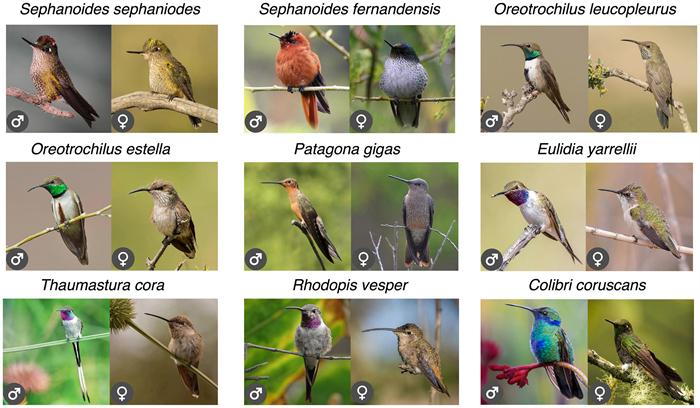

Only nine hummingbird species have been recorded in Chilean ecosystems (about 2.5% of the number of hummingbird species in the world). This is an extremely low figure in comparison to other South American countries such as Colombia (165 species, 48.7%), Ecuador (163 species, 48.1%) and Peru (118 species, 34.8%). The hummingbird species present in Chile are Oreotrochilus leucopleurus, Oreotrochilus estella, Sephanoides sephaniodes, Sephanoides fernandensis, Patagona gigas, Rhodopis vesper, Thaumastura cora, Eulidia yarrellii, and Colibri coruscans (Jaramillo et al., 2014, Fig. 1). The species Chlorostilbon lucidus (Red-billed Hummingbird) is recorded by Barros et al. (2014) as a wanderer in Chile, that is, as a species that is not part of the core avifauna in the country. Two out of nine Chilean species are endemic, the Arica hummingbird (E. yarrellii), and the Juan Fernández hummingbird (S. fernandensis). With the exception of P. gigas and S. sephaniodes, most Chilean hummingbirds have restricted distributions (Fig. 2). Regarding elevation, only two species of the genus Oreotrochilus, inhabit almost exclusively the Andes Mountains, the White-sided Hillstar (O. leucopleurus), which inhabits lower elevation zones (1500–3300 m) in Central Chile, and the Andean Hillstar (O. estella), which inhabits between 3500 and 5000 m in the northern margin of Chile. The species O. estella, P. gigas, and C. coruscans inhabit at elevations of 4000 m in Queñoa forests (Polylepis spp.) in northern Chile.

One of the distinctive characteristics of the Chilean hummingbird avifauna is its wide body size range (Vilina and Cofré, 2006), which ranges from 8 to 24 cm, including in the extremes the Arica Hummingbird (E. yarrellii), one of the smallest hummingbirds in the world, with only 8 cm in length and 4 g in mass, and the Giant Hummingbird (P. gigas), the second largest in the world, with 24 cm in length and 20 g in mass. In principle, this wide variation may result from morphological adjustments associated with flower resource partitioning. However, even though no phylogenetic analysis for Chilean species exists at present, it is likely that phylogenetic dispersion accounts better for body size difference as the nine Chilean species belong to four out of nine clades identified by McGuire et al. (2014). Standardized information on morphological characteristics of the Chilean hummingbird species as well as data on latitudinal and altitudinal distribution range, habitat type, estimated population size, population trends across time, conservation status and actions, and management plans can be found in Goodall et al. (1946, 1951), Araya and Millie (1992), Jaramillo et al. (2014), and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list at https://www.iucnredlist.org/.

Information on hummingbird-plant relationships in Chile is scarce and mainly limited to the species O. leucopleurus, P. gigas, S. sephaniodes, and S. fernandensis. Muschett and Fontúrbel (2022) compiled a list of plant-pollinator relationships with interaction recordings for the nine species in the country. Although there is a general floral syndrome associated with hummingbird pollination, Walter (2008) mentions that Chilean hummingbirds inhabiting arid environments tend to feed opportunistically on the nectar of plants with tubular flowers especially in the winter season when nectar availability is scanty. Even though some populations of S. sephaniodes may stay in some localities throughout the year, seemingly due to winter nectar sources such as mistletoes, all the hummingbirds present in Chile move latitudinally and altitudinally between seasons, following nectar resource availability (Jaramillo et al., 2014).

Information on this species is almost nonexistent in Chile. This is a high-altitude tropical species that distributes in the margins of the Andes Mountains from Venezuela to northern Chile and Argentina. This species seems to be in the process of geographical expansion associated with Eucalyptus spp. trees in high-elevation human populations (Martínez-Piña and González-Cifuentes, 2004; Estades, 2014). Feeding recordings for this species are limited to the northern margin of Chile, where it has been observed visiting flowers of Dunalia spinosa (Solanaceae), Malva sylvestris (Malvaceae), and Eucalyptus sp. (Myrtaceae) (Kuzmicic, 2015).

Information on the floral resources for this species is adequate but needs to be improved as E. yarrellii is an endemic endangered species (Estades et al., 2007). Chañar (Geoffroea decorticans, Fabaceae), constitutes its main food source in some localities (van Dongen et al., 2013; González-Gómez et al., 2015). This species has been observed visiting some native species, ornamentals, and crops. Cozano (2014) noted that E. yarrellii preferentially visits plants with small flowers, commensurate with its bill size (~1.5 cm). Among these, Pitraea cuneato-ovata (Verbenaceae) has characteristics that potentially could be used to supplement the nectar base for restoration purposes, such as rapid flowering and ease of emergence. It is interesting to note that E. yarrellii visits flowers with entomophilous rather than ornithophilous syndrome (Estades et al., 2007). Estades et al. (2007) also noted that Tecoma fulva (Bignoniaceae), one of the species with ornithophilic syndrome flowers, is highly visited by E. yarrellii once nectar robbers have damaged the flowers. The extent to which E. yarrellii is a secondary nectar robber for this species seems to be an interesting line of inquiry in this system. Regarding interspecific competition, E. yarrellii males have been reported to be dominant over T. cora and R. vesper males (van Dongen et al., 2013). This dominance seems to be ameliorated during the spring season, when resource use overlap tends to decrease (van Dongen et al., 2013). Additional evidence for the low importance of competition comes from the observation that the abundance of E. yarrelli and T. cora did not appear to be negatively correlated across sites and years. This finding contrasts with indirect suggestions of competition based upon spatial segregation between E. yarrellii and T. cora in the Azapa valley (Estades et al., 2007) and the absence of territory overlap between males of E. yarrellii and males of T. cora (Clark et al., 2013). It is likely that the shorter wings and higher flapping frequencies of E. yarrellii, compared to T. cora, provide E. yarrellii higher flight maneuverability and success in antagonistic encounters (Altshuler et al., 2004).

There is no information on the floral resources used by this species in Chile at present. This hummingbird inhabits high mountain habitats zone between Arica and Antofagasta, preferably in ravines and foothills vegetated with species of the genus Polylepis between 3000 m and 4200 m of elevation (Cofré, 2007).

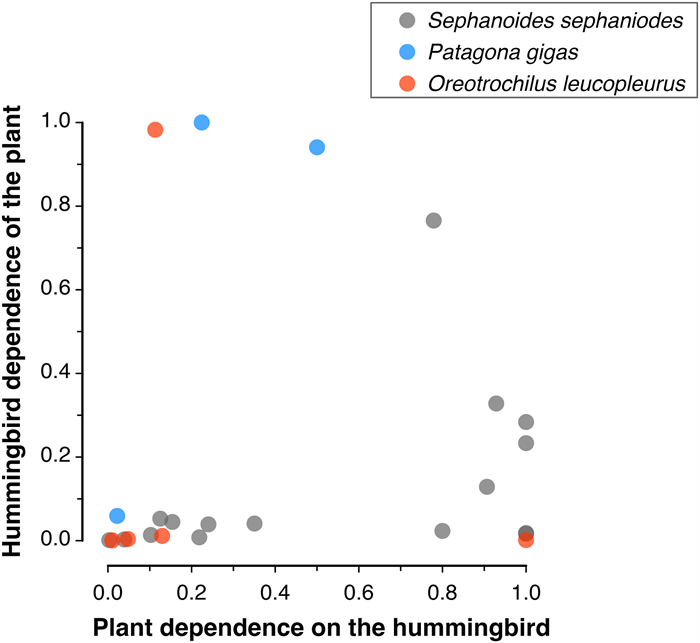

This species inhabits between 1500 and 3000 m of elevation and between 27° and 38° S (Jaramillo et al., 2014), although occasionally, it has been detected at lower altitudes (Walter, 2008). Although most of the information on floral resources for this species is confined to the Andes Mountain range near Santiago, O. leucopleurus is one of the species with the highest number of records of floral visits in the country. The species visits flowers of Schizanthus hookeri and Schizanthus grahamii (Solanaceae), species that form a single high Andean clade that, in principle, would have evolved in relation to hummingbird pollination (Pérez et al., 2006). Schizanthus grahamii presents a high level of self-fertilization, which has been suggested to result from its specialization on unpredictable hummingbird pollination (Pérez et al., 2009). Likewise, a series of studies have documented that O. leucopleurus is an important pollinator of Mimulus luteus in Central Chile. This hummingbird, together with bees, has been reported to represent an important selective force on different flower traits, with the hummingbird preferring flowers with smaller corollas and nectar guides than bees (Medel et al., 2003). Likewise, Pohl et al. (2006) experimentally demonstrated that O. leucopleurus increases seed production of M. luteus, except when flowers are damaged at the landing petal where the nectar guide is located. An analysis of seven M. luteus populations in Central Chile revealed that the more dominant the hummingbird is in the pollinator assemblages, the larger size of the M. luteus nectar guide, suggesting that the presence of bees interferes with hummingbird preferences under natural conditions (Medel et al., 2007). Casual information indicates that O. leucopleurus also feeds on the nectar of Tropaeolum polyphillum and Stachys sp. (Herrera et al., 2004). The only quantitative data correspond to records from three consecutive years in a plant-pollinator community in the Andes of Central Chile (32°51′ S, 70°08′ W, 2284 m a.s.l.; Medel et al. in progress). There, the White-sided Hillstar feeds on the nectar of Escallonia sp., Mutisia subusulata, Mimulus luteus, Ephedra chilensis, and Schizanthus hookeri. The levels of dependence of the plant species for this hummingbird as well as the hummingbird dependence for the plant species is depicted in Fig. 3.

This species is the largest hummingbird species in Chile at present, measuring 21–24 cm long. It inhabits a wide geographic range in South America that goes from the south of the western margin of Colombia to approximately 38° S, South-Central Chile. In Chile, it is restricted to high elevation environments in the north, with the highest elevation range occurring from Caldera onwards. Cofré (2007) notes that P. gigas is associated with Polylepis rugulosa forests in the pre-Puna habitat of the northern margin of Chile.

One of the first descriptions of the floral resources of this hummingbird in Chile is Johow (1921), who notes that this species frequently visits the cactus Echinopsis (= Trichocereus) chiloensis ssp. litoralis at Zapallar on the coast of Central Chile. However, recordings of floral visitors by Ossa and Medel (2011) and Medel et al. (2004) did not reveal the participation of this hummingbird in the pollination of this cactus species inland, at Las Chinchillas National Reserve. Likewise, Walter (2010) did not record visits to flowers of E. chiloensis spp. chiloensis in the Colchagua province, except for a casual sighting of a few individuals towards the end of the cactus flowering season. Recently Antinao et al. (2019) described that P. gigas is the main floral visitor of the coastal cactus Eriocyse subgibbosa, a species that depends on pollinators for reproduction, reaching at least 80% of visits recorded in observations performed in 2016 and 2017. It has been suggested that the arrival of P. gigas to the central region of Chile in the spring season coincides with the flowering of E. subgibbosa (Walter, 2008). In this regard, it is interesting to note that even though Eriosyce chilensis has, like E. subgibbosa, an ornithophilous floral syndrome, Antinao et al. (2019) did not record visits of P. gigas to this species, which supports the proposition of Gorostiague and Ortega-Baez (2016) that at least in cacti, ornithophilous flowers do not necessarily predict visitation by hummingbirds.

In the Andean mountains near Santiago, the Giant Hummingbird is the main pollinator of Eccremocarpus scaber, followed by S. sephaniodes (Belmonte et al., 1994). It is interesting to note that the nectar dynamics and composition of E. scaber are similar to those observed in plants that depend on nectar-eating bats for reproduction, which is probably related to the high energy demand of P. gigas, as documented by Fernández et al. (2011). It is likely that, due to its high energetic demand, P. gigas exhibits a high sensitivity to habitat loss, as evidenced by a high index of sensitivity to landscape change (Vásquez and Simonetti, 1999), and floral damage, as described by González-Gómez and Valdivia (2005) for Puya coreulea. A comparative analysis of the characteristics of Puya species visited by hummingbirds performed by Hornung-Leoni et al. (2013) indicates that P. gigas is an important pollinator for Puya venusta and P. coreulea (Bromeliaceae), species that produce a relatively low amount of nectar, albeit highly concentrated. In contrast, the Puya species that depend on a greater number and diversity of pollinators, such as Puya chilensis and Puya alpestris, produce abundant but low-concentration nectar. Specific records of the floral resources visited by P. gigas in Chile are provided in Ortiz-Crespo (1974), Ramírez (1940), and Barros (1952) and summarized in Appendix Table S1. Finally, and although not directly related to the consumption of floral resources, it is interesting to note the observation of ash consumption by P. gigas in a locality in Central Chile, which has been hypothesized to represent a way of calcium supplementation (Estades et al., 2008).

This hummingbird is a sexually dimorphic species that inhabits the coastal range from the Sechura desert in the Department of Piura in Peru to the southern part of northern Chile, with an intrusion towards more continental habitats around San Pedro de Atacama. In Chile, it is resident between 18° and 26° S, inhabiting pre-mountain valleys and agricultural areas with sufficient water irrigation (Jaramillo et al., 2014). It has two subspecies, Rhodopis vesper, which extends from northern Peru to the Tarapacá and Antofagasta regions, and Rhodopis vesper atacamensis, with a distribution from the Atacama Desert, in the vicinity of the Copiapó River valley. It is an intermediate-sized species (12 cm long) with a long and curved bill in relation to the other hummingbirds present in Chile. Although no quantitative recordings exist on its floral resources in Chile, the fact that in some places attacks and excludes the similar-sized (12–13 cm long) Peruvian Sheartail, T. cora, while in other nearby sites they share territory (Clark et al., 2013), suggests that R. vesper is highly sensitive to the patch structure of the floral resources, being able to coexist with other similar-sized hummingbirds depending on the nectar supply. Walter (2008) notes that this species may be considered a pollinator of the cactus Eriosyce taltalensis. Records of floral resources pending corroboration indicate that R. vesper in Chile consumes nectar from flowers of leguminous trees, agaves, Nicotiana sp. and that cacti are probably important components of its diet as well (Fjeldså and Krabbe, 1990; cited in Walter, 2008).

One of the most conspicuous characteristics of this species is its endemicity to the Juan Fernández Islands (Fig. 2), where it evolved in situ. Although the species used to inhabit both Alejandro Selkirk and Robinson Crusoe Islands, it is now considered extinct in Alejandro Selkirk, seemingly due to the action of rats and domestic cats (Busse, 1971; Hahn and Römer, 2002). Currently, the species is restricted to the Robinson Crusoe Island, where it has experienced a series of threats that have caused a significant decline in population size in recent decades (Brooke, 1987; Stiles, 1987; Colwell, 1989; Bourne et al., 1992; Roy et al., 1998, 1999). Among the factors involved in population decrease, predation by introduced mammals, habitat loss, degradation of the forest environment (Hahn et al., 2011), and the effects of exotic plants that reduce the abundance of the local flora (Bourne et al., 1992; Hahn and Römer, 2002; Hahn et al., 2011; Vargas et al., 2013) have been indicated as the most important menaces. Additionally, different sources of evidence suggest a possible interspecific competition between S. fernandensis and the colonizer from mainland S. sephaniodes (Colwell, 1989; Roy et al., 1999; Wolf and Hagen, 2012; Vizentin-Bugoni et al., 2017), the latter being more efficient in exploiting some floral resources (Hagen, 2009).

Some hummingbird-pollinated plants may play a crucial role in the persistence of S. fernandensis. For example, Sophora fernandeziana seems to be a critical species as its flowering season coincides with the lack of alternative floral resources available for hummingbirds (Bernardello et al., 2004). Interestingly, S. fernandensis has one of the most sexually dimorphic plumage chromatism and size in the Trochilidae family (Colwell, 1989). The female has a turquoise green and whitish ventral coloration and is 66% smaller than the brick red male (Johnson and Goodall, 1967). This strong sexual dimorphism led to initial errors in classification, as sexes were assigned to different species (Colwell, 1989). Unlike most hummingbirds, both sexes actively defend different foraging territories using similar territorial behavior (Colwell, 1989). Sephanoides fernandensis feeds on nectar produced by Dendroseris litoralis and introduced species such as Eucalyptus globulus and Paraserianthes lophantha. Despite the strong sexual dimorphism, the bill size of males and females is similar (~ 15 mm), suggesting that no partitioning of floral resources between both sexes has occurred (Colwell, 1989).

In historical terms, the relationship between S. fernandensis and its floral resources in the Archipelago is of great interest due to the distance of Juan Fernández Island from the mainland (667 km) and the high degree of endemism of the interacting plant species. At least 127 species of endemic flora have been described in the Archipelago, which places the islands as those with the highest richness of endemic species per unit area of the world (Stuessy, 1992; Hahn, et al. 2009). Juan Fernández Island has an estimated age of 3.8–4.2 million years (Stuessy et al., 1984), and the in-situ evolution of S. fernandensis from an ancestor similar to Sephanoides sephaniodes, suggests a long coevolutionary history between S. fernandensis and the angiosperms of the island. Bernardello et al. (2002) report that about 9% of the angiosperms of the island are positively pollinated by birds, with 44% of the flora having unknown pollination. Although some species, such as Wahlenbergia berteroi, may show floral traits suggestive of bird pollination, only dipterans and ants have been recorded on this species, adding an additional layer of complexity to a putative identification of floral visitors based on island pollination syndromes (Anderson et al., 2000, 2001; Alarcón et al., 2014).

The absence of native bees in the Archipelago makes it feasible that many of the species that make up 44% of the flora with unknown pollination are visited by hummingbirds. However, historical contingencies related to changes in the composition of the island biota, local extinctions, possible mainland-island replacement of pollinators, and colonization of genera with mixed pollination systems may substantially limit the predictive power of pollination syndromes in the Juan Fernández Archipelago. Indeed, Bernardello et al. (2002) state that four genera changed from a system associated with insect pollination on the mainland to one of pollination by hummingbirds on the island (Rhaphithamnus, some Eryngium, Centaurodendron, and some Dendroseris) and other seven genera retained their mainland characteristics of pollination by hummingbirds (e.g., Greigia, Ochagavia, Lobelia, Sophora, Cuminia, Nothanthera, and Escallonia).

This small hummingbird species (9–11 cm) is the most common in Chile. It has a wide distribution that extends from the Atacama Region to Tierra del Fuego (Fig. 2), being also present in the Juan Fernández archipelago (Jaramillo et al., 2014; Medrano et al., 2018). This species inhabits diverse habitats, from forests and natural environments to urban and disturbed areas, depending on flower availability (Jaramillo et al., 2014). Most populations are migratory during the breeding season (spring), migrating from Central Chile southward, coinciding with the flowering season of some species in southern Chile (Medrano et al., 2018). During the winter, hummingbird populations inhabit mostly central-northern Chile, which is coincident with the profuse flowering of the mistletoe Tristerix aphyllus in May–July (Medel et al., 2002). There are also resident populations in humid ravines between 29° and 44° S (Medrano et al., 2018).

Regarding feeding habits, S. sephaniodes is a generalist nectarivorous species that feed upon native and introduced floral resources. In Central Chile, it visits species showing red flowers, such as T. aphyllus, Tristerix corymbosus (Loranthaceae), Lobelia polyphylla (Campanulaceae), and species showing white flowers, such as Sophora macrocarpa (Papilonaceae) and the exotic tree E. globulus (Myrtaceae) (Fernández et al., 2002; Cuadra-Valdés et al., 2021). According to Walter (2008), it is likely that Eriosyce sociabilis and Eriosyce villosa (Cactaceae) are visited exclusively by S. sephaniodes. In the Coastal Mountain Range, large numbers of hummingbirds have been observed visiting flowers of Porlieria chilensis, probably attracted by the concentrated nectar produced by this species (Medrano et al., 2018). In the Maulino Forest (Central Chile), S. sephaniodes visits Lapageria rosea, a species endemic to temperate forests that currently experiences a decreasing pollination by hummingbirds due to forest fragmentation, especially in the most fragmented areas (Valdivia et al., 2006). Other species from the Maulino Forest that receive pollination service by the hummingbird include Desfontainia spinosa (Desfontainiaceae), Lobelia tupa (Campanulaceae), and Fuchsia magellanica (Onagraceae) (Rivera-Hutinel et al., 2012). Sephanoides sephaniodes is also a frequent visitor of Colletia ulicina (Rhamnaceae), a plant endemic to Central Chile (Medan and Montaldo, 2005).

In the temperate forests of the Chiloé Island, S. sephaniodes pollinates about 20% of the native flora, visiting mainly the flowers of F. magellanica (Onagraceae), E. coccineum (Proteaceae) and T. corymbosus (Loranthaceae) (Smith-Ramírez, 1993; Smith-Ramírez and Armesto, 2003; Medrano et al., 2018). It is important to note that, during the austral winter, this hummingbird mostly visits the flowers of T. corymbosus, being this interaction key to determine the winter permanence of their populations in Chiloé as flowers of T. corymbosus are almost the only source of nectar available (Smith-Ramírez, 1993; Aizen et al., 2002).

This species exhibits a conspicuous sexual dimorphism, with males showing a very distinctive long tail. Thaumastura cora can be observed in the Azapa and Lluta Valleys in northern Chile (Jaramillo et al., 2014). Estades et al. (2007) described this species as dominant over E. yarrellii, which seemingly determines the low abundance of the Chilean Woodstar in some months of the year. According to Clark et al. (2013), T. cora is in a conservation status of least concern. Regarding floral resources, few recordings exist in Chile. It is known that it feeds on the nectar of Tecoma fulva flowers (Bignoniaceae), but the short bill of T. cora probably precludes legitime pollination service, limiting the species to secondary robbing after corolla piercing by the passerine Conirostrum cinereum (Clark et al., 2013). While the presence of T. fulva is included within the territories of T. cora males, it is unclear whether hummingbirds defend their territories in relation to the flower resource provided by this plant (Clark et al., 2013).

From the nine species of hummingbirds present in Chile, only S. sephaniodes resides year-round in a wide distribution throughout Chile. Oreotrochilus leucopleurus and P. gigas have a relatively wide but seasonal (summer) distribution in mountain and coastal sectors, respectively. Two species are resident in a restricted area of continental Chile (O. estella and R. vesper), and the remaining four species are resident in a very restricted area of the country: in the northern margin of Chile (E. yarrellii, T. cora, and C. coruscans), and on the Juan Fernández Island (S. fernandensis). Regarding their conservation status, two species (E. yarrellii and S. fernandensis) are classified as Critically Endangered by the IUCN, while the rest is classified as of Least Concern (see Appendix Table S1). However, the amount of information is quite limited for the seven Least Concern species. This lack of information is by itself a threat, as the way species respond to human-induced environmental change is unknown. In this regard, the species with the most restricted distribution (i.e., S. fernandensis, E. yarrellii, T. cora, and C. coruscans) seem to be the most sensitive to anthropogenic habitat change, deserving more study. In the case of P. gigas, which is present during the summer season in the Mediterranean region of Chile, it has been described as a species sensitive to habitat loss and transformation, probably because of its small clutch size, which turns this species sensitive to land-use change and landscape structure (Vásquez and Simonetti, 1999).

Sephanoides sephaniodes is by far the most studied Chilean species, probably due to its wide distribution range and its generalist habit that allows individuals to be found in a wide diversity of environments (from native forests to urban areas). In particular, S. sephaniodes is responsible for pollinating 20% of the woody flora of the temperate forests of southern Chile (Smith-Ramírez, 1993), which is one of the highest biotic pollination incidence rates in the world (Aizen et al., 2002). In recent years, however, these forests have experienced rapid deforestation, fragmentation, and degradation as a result of the expansion of exotic forest plantations (mostly pine and eucalyptus plantations), cattle pastures, and urban areas (Echeverría et al., 2006). Although S. sephaniodes is able to persist in deforested and degraded areas, the ecological consequences of the new scenarios are often subtle, and still few understood. For example, as S. sephaniodes nest-building basis on a non-random selection of moss species, any disturbance affecting moss populations will impact on hummingbird nesting behavior (Osorio-Zuñiga et al., 2014). Likewise, even though forest degradation and transformation simplify habitat structure and convey the proliferation of shade-intolerant plants such as Aristotelia chilensis, Ugni molinae, Rhaphithamnus spinosus, Lapageria rosea, among others (Fontúrbel et al., 2017a), this effect is accompanied by a change in the spatial structure of plants, creating large discrete aggregations of resource in space (Fontúrbel et al., 2017b). Interestingly, these changes in the identity, abundance, and spatial configuration of ornithophilous flowering plants in disturbed environments create foci of attraction for S. sephaniodes that result in some cases in reduction of pollen movement, and increased inbreeding and loss of genetic diversity (Fontúrbel et al., 2019). In this way, despite this apparent benefit conferred by disturbed environments in terms of diversity and quantity of floral resources, there are hidden population costs with unknown consequences for population persistence. Finally, exotic species (e.g., Eucalyptus globulus) may also play an important role in modifying the abundance and behavior of S. sephaniodes as reported in Cuadra-Valdés et al. (2021). Eucalyptus plantations attract hummingbirds from adjacent native forest patches, especially during Eucalyptus flowering, with unknown consequences for the reproduction of the native plant species in the temperate forest.

Few quantitative information on the flowering plants visited by hummingbirds is available. Most evidence is at most qualitative, which precludes generalization on hummingbird-plant pollination network structure. Notwithstanding, the few information available for three out of nine hummingbird species indicates that patterns of mutual dependence tend to show a trend for hummingbirds to present low degrees of dependence on plants, and plants to spread their dependency values along the complete range of dependence (Fig. 3). This asymmetry suggest that hummingbirds tend to be generalists rather than specialized on a few plant species, and plants tend to be variable regarding their dependence upon hummingbirds, ranging from extremely low to maximum dependence values (Fig. 3). On the other hand, visual inspection reveals that data tend to concentrate at low reciprocal values of mutual dependence, as it has been observed in large datasets of pollination and seed dispersal networks (Bascompte and Jordano, 2007). Clearly, more information is needed to extract more conclusive patterns of mutual dependence.

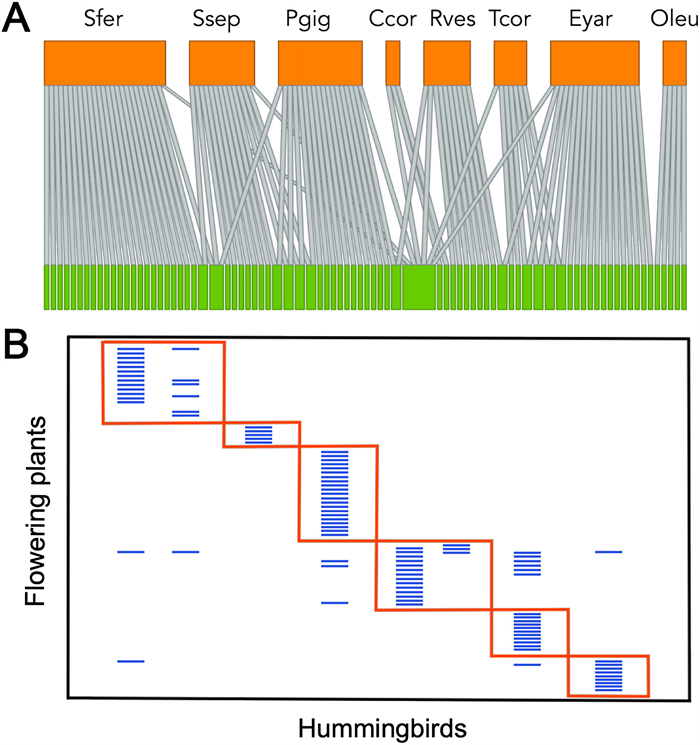

When the relationship among hummingbirds (based on eight species, as no information currently exists for Oreotrochilus estella) and their flowering plants (83 species) is shown as a bipartite metanetwork (i.e., a general network made of several individual networks), the hummingbird species show a very low overlap in the plants they visit (overlap = 0.095; Fig. 4A; detailed information is available in Appendix Fig. S1), which is consistent with the low network connectance (C = 0.154, the fraction of realized links relative to the total possible). The matrix of interactions showed a strong and significant modularity (null model, P < 0.001), with six well-defined modules (Fig. 4B; detailed information is available in Appendix Fig. S2). However, this result should be interpreted with caution as hummingbird species show strong allopatric distribution in Chile, with five species inhabiting the northern region of Chile, one species restricted to the Juan Fernández archipelago that mainly feed on plant species endemic to the island, and three inhabiting central and southern Chile. In consequence, the low connectance and niche overlap shown by hummingbird species, as well as the high modularity in resource consumption, may result from their allopatric condition and identity of the plants visited rather than from an ecological network organization (see Olesen et al., 2007).

From the nine hummingbird species present in Chile, only S. sephaniodes have adapted well to urban areas, which probably results from its generalist behavior. Cities offer an ecological setting that can provide a significant diversity of ornamental ornithophilous flowers, providing food for several species of hummingbirds (Maruyama et al., 2019). In addition, the use of artificial feeders in urban environments may create local changes in hummingbird behavior and abundance with no negative effects on the pollination of plants near the feeders (Sonne et al., 2016). Urban environments are often dominated by highly generalist and territorial hummingbird species that establish mutualistic interactions regardless of the origin (native or exotic) of the ornithophilous plant species present (Maruyama et al., 2016). Much remains to be known about the structure of plant-hummingbird interactions in Chile's urban environments. Although so far, only S. sephaniodes has been reported in this role, other Chilean hummingbirds may contribute to the maintenance of plant species depending exclusively on them for reproductive success in modified environments.

Along with climate change, habitat loss and the introduction of exotic species emerge as the major forces for the change in ecological setting of hummingbirds and pollination. In Central Chile, habitat loss associated to the spread of commercial crops has reduced substantially the abundance of plant species that provide abundant nectar for hummingbirds, such as Puya species (Puya coerulea, Puya venusta, Puya chilensis, Puya alpestris, and Puya berteroniana; Bromeliaceae). While these species are not currently listed as endangered, their reduction in numbers attributable to land use change and even to the direct removal for gastronomy purposes, may have an indirect detrimental impact on hummingbirds as the nectar needed to support populations of S. sephaniodes and especially the giant and energy demanding P. gigas might be severely compromised. In addition, recent evidence shows that the occurrence of prolonged drought events, which are becoming more frequent and intense in Chile (Boisier et al., 2016; Garreaud et al., 2017), tend to reduce flower and fruit production in some species due to water stress (Fontúrbel et al., 2018). During extremely dry years, plants experience strong nectar depletion as hummingbirds have fewer flowers on which to feed upon (Guerra et al., 2014) and receive less pollination service in return. Unfortunately, this pattern is not unique to Chile but has also been documented in other latitudes (Phillips et al., 2018) and is probably more common than previously thought. Cacti species also represent an important source of nectar for hummingbirds. Most species of the genus Eriosyce subgen. Neoporteria in Chile produce abundant nectar and have flowers relatively specialized in hummingbird pollination (trochilophilous syndrome sensu Schmidt-Lebuhn et al., 2007), such as O. leucopleurus, P. gigas, R. vesper and S. sephaniodes (Guerrero et al., 2012). The high specialization values shown by those cacti turns them especially susceptible to reduction in hummingbird population numbers, which probably compromise their reproduction and outcrossing. This effect together with the increasing temperature and decreasing precipitation observed in the earth's biota (Walther et al., 2002; Parmesan, 2006), will have the effect of intensifying the disruption of hummingbird-plant pollination interactions (Memmott et al., 2007; Walck et al., 2011), making them susceptible to population extinction and probably eliciting coextinction processes beyond those directly observed in hummingbirds and their plants (Sonne et al., 2022).

This review compiled the evidence available for the nine Chilean hummingbird species found in this country, which are an interesting model study given their ecological specialization patterns given Chile's biogeographical context (i.e., a continental island, isolated from other ecosystems by major geographical barriers such the Andes mountains and the Atacama Desert). With the exception of S. sephaniodes and P. gigas, Chilean hummingbirds have restricted distributions. Such allopatric arrangement may explain the marked modularity observed when examining their interaction with floral resources, which suggests a high ecological specialization. Therefore, given the high specialization of hummingbird-plant interactions in Chilean ecosystems, they may be very sensitive to anthropogenic threats (particularly land-use change and climate change) as there is little functional redundancy.

While our knowledge on some Chilean hummingbird species and their interactions with flowering plants remains limited, this review provides a comprehensive synthesis that may encourage further research on this topic, particularly on those species with restricted distributions, which ecological knowledge is currently scarce and mainly anecdotic. We urge to conduct quantitative studies to improve our understanding on those ecological relationships and how global change can threaten not only hummingbirds but also many plant species that depend on them for pollination and reproduction.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

We thank M. Sallaberry for the initial stimulus to write this review and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback. RM gratefully acknowledges funding from FONDECYT 1180850 and CYTED 418RT0555. MLA and FEF acknowledge the support of project ANID/PIA/ACT192027. FEF also acknowledges the support of ANID – Millennium Science Initiative Program– NCN2021-050, and Fundación San Ignacio del Huinay.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avrs.2022.100051.

|

Allport, G.A., Atkinson, P.W., Carvalho, M., Clark, N.A., Green, R.E., 2018. Local site use and frst northbound migration track of non-breeding Steppe Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus alboaxillaris (Lowe 1921). Wader Study 125, 219–227

|

|

Arlott, N., 2018. Birds of the Philippines, Sumatra, Java, Bali, Borneo, Sulawesi, the Lesser Sundas and the Moluccas. William Collins, London.

|

|

Baker, R.H., 1951. The Avifauna of Micronesia, Its Origin, Evolution, and Distribution. University of Kansas, Lawrence.

|

|

BirdLife International, NatureServe, 2015. Bird Species Distribution Maps of the World. BirdLife International and Arlington: NatureServe, Cambridge.

|

|

Bishop KD. Shorebirds in New Guinea: their status, conservation and distribution. Stilt. 2006;50:103-134

|

|

Carneiro C, Gunnarsson TG, Alves JA. Faster migration in autumn than in spring: seasonal migration patterns and non-breeding distribution of Icelandic whimbrels Numenius phaeopus islandicus. J Avian Biol. 2019;e01938

|

|

Cramp SC. Handbook of the birds of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. The birds of the Western Palearctic. Vol.3. Waders to gulls. Oxford: Oxford university press; 1983

|

|

Crossland AC, Butcher S, Crutchley P, Mugan ND, Kake J. A survey of waders on part of Guadalcanal and the Florida group, Solomon Islands. Stilt. 2016;69-70:48-56

|

|

Deignan HG. Checklist of the birds of Thailand. Washington, Smithsonian Institution;1963

|

|

del Hoyo J, Collar NJ. HBW and Birdlife International illustrated checklist of the birds of the world. Vol.1. Non-passerines. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions; 2014

|

|

Gill BJ, Bell BD, Chambers GK, Medway DG, Palma RL, Scofield RP, et al. Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. 4th ed. Wellington: Te Papa Press; 2010

|

|

Grantham MJ. A note on the passage of variegatus and phaeopus type whimbrels through Alas Purwo National Park, East Java. Kukila. 2000;11:133-135

|

|

Hayman, P., Marchant, J., Prater, T., 1986. Shorebirds: An Identification Guide to the Waders of the World. Croom Helm, London

|

|

Iqbal M, Ridwan A. Summering of whimbrel in southern Sumatra, Indonesia. Stilt. 2009;55:20-24

|

|

Jeyarajasingam A. A field guide to the birds of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012

|

|

Jorgensen AA. Siams Vadefugle. III. Charadriiae (Tringinae). Dansk Orn For Tidsskr. 1949;43:216-237

|

|

Lappo EG, Tomkovich PP, Syroechkovski EE. Atlas of breeding waders in the Russian Arctic. Moscow: UF Ofsetnaya Pechat; 2012

|

|

Lekagul, B., Round, P. D., 1991. A Guide to the Birds of Thailand. Saha Karn Bhaet, Bangkok

|

|

MacKinnon J, Phillipps K. A field guide to the birds of Borneo, Sumatra, Java, and Bali (The Greater Sunda Islands). Oxford: Oxford university press; 1993

|

|

Newton I. The migration ecology of birds. London: Academic Press; 2008

|

|

Phillips WWA. A 1975 annotated checklist of the birds of Ceylon (Sri Lanka). Colombo: Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Ceylon; 1975

|

|

Prater AJ, Marchant JH, Vuorinen J. Guide to the identification and ageing of Holarctic waders. Tring: BTO; 1977

|

|

Ripley SD. A synopsis of the birds of India and Pakistan: together with those of Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. Bombay: Bombay natural history society; 1982

|

|

Robinson HT, Chasen FN. The birds of the Malay Peninsula, Vol. 3: sporting birds, birds of the shore and estuaries. London: Witherby; 1936

|

|

Robson C. New Holland field guide to birds of South-East Asia: Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar. London: New Holland; 2005

|

|

Stinson DW, Wiles GJ, Reichel JD. Occurrence of migrant shorebirds in the Mariana Islands. J Field Ornitol. 1997;68:42-55

|

|

Tomkovich PS. A new subspecies of the whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus) from central Siberia. Zool Zurnal. 2008;87:1092-1099

|

|

Wells DR. The birds of the Thai-Malay Peninsula, Vol. 1: non-passerines. London: Academic Press; 1999

|