| Citation: | Yuxiang LI, Changzhan SONG, Yucheng YANG, Xiaojing LI, Fengli LI, Jie HUANG, Xiuli HUANG. 2012: Monitoring population dynamics of the migratory Red-crowned Crane (Grus japonensis) at Shuangtaihekou National Nature Reserve, northeastern China, from 1991 to 2012. Avian Research, 3(3): 225-229. DOI: 10.5122/cbirds.2012.0029 |

We studied migratory Red-crowned cranes from 1991-2012 in order to track population dynamics and trends for these cranes over time at Shuangtaihekou, northeastern China. Our results show that the earliest arrival date of the Red-crowned Crane (Grus japonensis) was usually around 1 March in the spring and the latest departure date of the cranes around 8 November. The peak period for the number of cranes observed in the spring was 10-20 March over these 22 years. The staging period in the spring is about 25 days. Comparing the highest number of Red-crowned cranes observed in the spring, the migratory population was around 400 birds in the 1990s, then, increased to over 800 birds in 2000. For a short while, the population maintained itself around 600-800 birds. After that, the population started to decline, until during the most recent years, we observed around 400 birds at peak times of each season. Our results match a similar population change pattern observed in the wintering area for a western population, which has been declining since 2000. There is an urgent need to reinforce protection and management, as well as to maintain and improve the quality of their habitats.

The Red-crowned Crane (Grus japonensis) is a globally threatened species (IUCN, 2012). Long-term monitoring is highly important to identify changes in its population variables, to provide data related to the probable causes of change and to assist policy makers and reserve managers in setting up more timely and effective measures for conservation of the species (Ballie, 1990; Marsh and Trenham, 2008).

Shuangtaihekou National Nature Reserve (hereafter Panjin) is located in the northern part of Bo Bay. It is an important stopover site for many migratory birds on the East Asian-Australia Flyway (Harris, 2009). During migration seasons, large numbers of cranes and other waterbirds — including the Red-crowned, Siberian (G. leucogeranus) and Hooded (G. monacha) cranes, Oriental White (Ciconia boyciana) and Black (C. nigra) storks, the Swan Goose (Anser cygnoides), other swans, and many species of ducks and shorebirds — stopover or pass by the Panjin wetland (Jin and Lian, 1992; Jin et al., 1997). The Panjin wetland also is the largest breeding ground for the Saunders's Gull (Larus saundersi). There are about 8000 Saunders's Gulls, 80% of the world population, breeding here (Jiang et al., 2010).

Panjin wetland is located at the mid point of the migration route between breeding and wintering grounds for the Red-crowned Crane and is one of the main stopover sites for its western population (Wang and Yang, 2005). Panjin is also the southernmost breeding area for the Red-crowned Crane.

We recorded the number and stopover periods of Red-crowned Cranes in each spring and the departure dates for the cranes in autumn from 1991–2012, in order to track their population dynamics and trends over time. In autumn, the tall reedbeds make it very difficult to count the cranes, so we did not attempt to determine stopover periods.

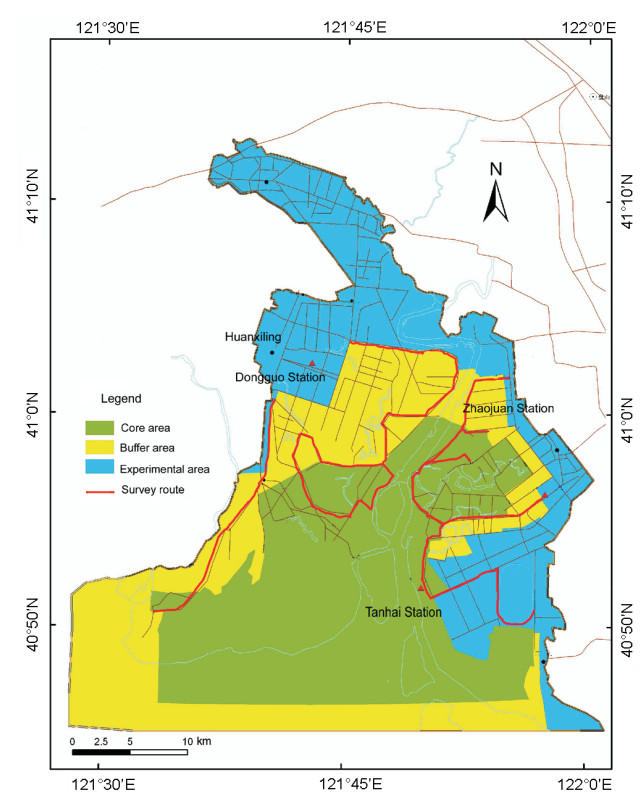

Shuangtaihekou National Nature Reserve (NNR) is located at the northern part of Liaodong Bay (northeastern part of Bo Bay) (40°45′–41°10′N, 121°30′–122°00′E). It is a sedimentary plain of the Liao, Daling and Daliao rivers, covering an area of 128000 ha (Fig. 1). It is a coastal wetland, with reed marshes, wet meadows, man-made wetlands (rice paddies and reservoirs), river channels, estuaries, mudflats and shallow sea water wetlands. The reserve is located within the temperate monsoon zone, with an average annual temperature of 8.4℃ and a frost-free period of about 167–174 days. Annual rainfall is 623.2 mm, with a recorded maximum of 916 mm and a minimum of 326 mm. The annual evaporation is about 1669.6 mm. The annual daylight is 2768.5 hours. There are four seasons. In the spring (March-May), the temperatures rise quickly, the weather is dry with little rain, a prevailing south wind, a high rate of evaporation and increasing number of daylight hours.

During April–May, there are 14 days with a level 8 wind, which accounts for about 35% of annual high wind days; rainfall is about 90.0 mm accounting for 15% of annual rainfall; evaporation is about 585 mm and 60% of the annual rainfall occurs in these two weeks. Autumn (September–November) has mostly clear days, with sunlight time of about 670 hours, i.e., about 24% of annual sunlight. Winter extends from December to February and is dry and cold. January is the coldest month, with an average temperature of –10.3℃; the coldest temperature recorded is –29.3℃ and precipitation is only 16 mm, about 2.5% of annual rainfall.

A total of 271 bird species have been recorded, including 118 waterbirds (Jin et al., 1991, 1997; Wang et al., 1994, Y. Li, personal data). Among these are six crane species: Siberian, Red-crowned, Hooded, White-naped (G. vipio), Eurasian (G. grus) and Demoiselle (Anthropoides virgo) cranes.

In the spring migration seasons during 1991–2012, from early March to early April, we carried out field surveys of the cranes at intervals of 7–10 days. We conducted at least one survey at the peak time when most cranes were present, usually around March 15. The surveys were made on clear days without wind. Our study days could shift forward or move back 2–3 days based on the weather.

Because all the reed has been harvested in the previous winter, there were no visual barriers for us in searching for cranes. During our field surveys, we drove along selected roads that in total were about 110 km in length and covered every potential crane habitat in the reserve (Fig. 1). Our survey coverage extended about 1500–2000 m on each side of the road. Once we found cranes with 8× binoculars, we would stop and use a 20–60× scope to confirm, then count and record the cranes directly. To avoid double counting when the birds moved over a large range, all field workers were divided into two groups. The groups did a synchronized count from the east and west sides of the Shuangtai River. We communicated when the cranes were flying, to alert the other teams about the directions the birds were flying and their landing spot.

The general migratory patterns for the Red-crowned cranes can be identified as follows. In the spring, the birds arrive in small flocks of 5–10 at the beginning; then, quickly after 3–5 days the large flocks arrive. All the cranes are stopping here and the population builds up. Then, suddenly they all depart within 2–3 days when the weather changes in late March. In the fall, the cranes come in scattered small flocks usually in family groups, 2–4 birds, or in small flocks of 5–15 birds. They are leaving gradually, too. Also the reeds are tall in the autumn so that it is hard to see all the birds or obtain good counts.

Over the 22 years, the first arrival dates in the spring for Red-crowned cranes were usually around March 1 (Table 1). The mean arrival date was February 28 ± 5.36 days (range: February 12 – March 5). In 1999, the cranes arrived unusually early, on February 12. If we consider 1999 an outlier and delete it from our analysis, the variation in arrival date was 11 days over the years and the mean arrival date was March 1 ± 3.44 days. For 15 years the cranes first arrived in March and for only 7 years they first arrived in February. By March 25, all migratory cranes have departed and only the breeders stay.

| Year | First day seen in spring | Last day seen in fall | Year | First day seen in spring | Last day seen in fall | |

| 1991 | Mar2 | Nov 3 | 2002 | Mar 3 | Nov 14 | |

| 1992 | Mar 4 | Nov 2 | 2003 | Mar 2 | Nov 5 | |

| 1993 | Feb 27 | Oct 28 | 2004 | Feb 26 | Nov 9 | |

| 1994 | Mar 5 | Nov 7 | 2005 | Mar 3 | Nov 5 | |

| 1995 | Mar 3 | Oct 27 | 2006 | Mar 2 | Nov 8 | |

| 1996 | Feb 28 | Nov 9 | 2007 | Feb 28 | Nov 4 | |

| 1997 | Mar 1 | Nov 6 | 2008 | Mar 5 | Nov 18 | |

| 1998 | Mar 2 | Nov 13 | 2009 | Mar 1 | Nov 20 | |

| 1999 | Feb 12 | Nov 6 | 2010 | Mar 2 | Dec 21 | |

| 2000 | Feb 26 | Nov 18 | 2011 | Mar 3 | Wintering individuals | |

| 2001 | Feb 28 | Nov 6 | 2012 | Mar 1 |

From 21 years of fall observation records, the latest departure dates in the fall for the Red-crowned Crane were usually around November 7 (Table 1). The mean latest departure date was November 9 ± 11.21 days (range: October 27 – December 21). The last cranes left very late on December 21 in 2010. In the following winter, 2011–2012, five birds remained for the entire winter at the Panjin wetland. If we consider 2010 an outlier and delete it from the analysis, the variation was 25 days over the years in the fall and the mean latest departure date was November 8 ± 6.18 days. There were only two years, 1993 and 1995, when the last cranes left before November.

The peak period over the 22 years for the number of cranes observed in the spring was March 10–20. The highest record was 808 cranes on March 21, 2000 and the lowest number was 308 cranes on March 14, 1995 (Fig. 2). The highest number for a single flock was 412 birds on March 13, 2000 in a reed bed east of Zhaoquanhe Station.

By comparing the annual highest counts of Red-crowned Cranes in the spring, we conclude that the migratory population was around 400 birds from 1991 to 1998, then increased to over 800 birds in 2000. During the period of 2000–2004, the population maintained relatively high numbers of 600–800 birds. After that, the population started to decline, until in the most recent years, we observed around 400 birds at peak times of each season.

There was considerable variation among years in the dates of early spring arrivals and late fall departures; however, we did not detect any change in the trend of early arrival dates in the spring and latest departure dates in the fall. There is no significant correlation with time for the dates of earliest arrival and latest departure. Although, we observed a very late departure in 2010 and a few individual birds stayed for the winter in 2011–2012, it is too early to say that the cranes leave later now than before, based on the data from only two seasons.

Compared with other studies at different locations, our results indicate that Panjin has the largest staging population of Red-crowned cranes in China (Williams et al., 1991; Shan et al., 2005, 2007; Wang et al., 2005). The duration of stay for migratory Red-crowned Cranes at Panjin have been longer than at any other staging area. It seems that the entire western population of the Red-crowned Crane passes through Panjin. All these birds stay here for resting and feeding to regain the energy needed to continue their journey. These factors make Panjin a very important location for conservation of the species; therefore, it is important to continue and strengthen our monitoring program.

Through our monitoring, we not only have come to understand the population changes at Shuantaizihekou NNR, but it also allows us to reflect on the dynamics of the western population. Our results match a similar change in the population pattern observed in the wintering area for the western population which has been declining since 2000 (Wang et al., 2005; Su et al., 2008).

Given our more than twenty years of observations, it appears that environmental changes and intensive human disturbances form serious threats to the cranes. In the Shuantaizihekou NNR, enhanced management measures to increase the productivity of reeds causes plant diversity to decrease; overfishing and draining of the reed beds before harvest result in poor fish resources, lack of water in the wetlands in the spring and less food for the birds. Also, if we take a broad view along the flyway, reductions in size and quality of the wetlands have forced cranes to forage in farmlands and other areas, creating greater risks for the cranes to be poisoned (Hu et al., 2004; Su and Zou, 2012). Loss and degradation of wetlands is one of the primary causes for the decline in the crane population (Wan et al., 2002).

Based on recent population changes, we conclude that the Red-crowned Crane population is in critical condition in China. There is an urgent need to reinforce protection and management, to maintain and improve the quality of their habitats and to establish a monitoring program at multiple sites.

|

Baillie SR. 1990. Integrated population monitoring of breeding birds in Britain and Ireland. Ibis, 132: 151–166.

|

|

Harris JT. 2009. Safe Flyways for the Siberian Crane. UNEP/GEF Siberian Crane Wetland Project, Regional Coordination Unit, International Crane Foundation, Baraboo, Wisconsin, USA.

|

|

Hu YM, Shu Y, Li XZ, Wang L, Li YX, Yang YC. 2004. Change of red-crowned crane breeding habitat and the analysis of breeding capacity in Shuangtaihekou National Nature Reserve. Chin J Ecol, 23(5): 7–12. (in Chinese)

|

|

Jiang HX, Hou YQ, Li YX, Takeishi M, Ozaki K, Yang YC, Zheng GM. 2010. Using marked individuals to explore migration pattern and estimate survival rates of Saunders's gull at Shuangtaihekou National Nature Reserve, China. Acta Ecol Sin, 30(15): 4180–4186. (in Chinese)

|

|

Jin LK, Lian Y. 1992. Study on Anatidae in Panjin. Liaoning Forest Tech, 5: 32–37, 18. (in Chinese)

|

|

Jin LK, Lian Y, Zhang YW. 1997. Charadriiformes birds in Panjin. Liaoning Forest Tech, 2: 26–29. (in Chinese)

|

|

Shan K, Lu JZ, Zhu SY, Yu HL, Zhou L. 2005. Number and habitat protection of the cranes in Yellow River Delta. In: Wang Q, Li F (eds) Crane Research in China. Yunnan Education Publishing House, Kunming, pp 66–73. (in Chinese)

|

|

Shan K, Zhang CH, Zhang HY. 2007. Migration behavior of crane to south in Yellow River Delta Nature Reserve. Chin J Wildl, 28(3): 36-38. (in Chinese)

|

|

Su L, Jiang HX, Qian FW, Wang H, Shan K. 2008. The red-crowned crane wintering population declines during last three winters in China. China Crane News, 12(2): 12–18. (in Chinese)

|

|

Su L, Zou HF. 2012. Status, threats and conservation needs for the continental population of the Red-crowned Crane. Chinese Birds, 3(3): 147–164.

|

|

Wan DM, Gao W, Wang QY, Wang HT, Liu MY. 2002. Effects of habitat fragmentation on nesting site selection of Red-crowned Crane. Chin J Appl Ecol, 13(5): 581–584. (in Chinese)

|

|

Wang H, Wang QS, Chu GZ, Jiang HX, Qian FW. 2005. Population change and distribution of red-crowned cranes wintering at Yancheng Nature Reserve. In: Wang Q, Li F (eds) Crane Research in China. Yunnan Education Publishing House, Kunming, pp 49–57. (in Chinese)

|

|

Wang QS, Yang ZF. 2005. Review of crane research in China. In: Wang Q, Li F (eds) Crane Research in China. Yunnan Education Publishing House, Kunming, pp 3–18. (in Chinese)

|

|

Wang ZC, Li YX, Yang FL, Wei HY, Sui FK, Li XJ. 1994. An observation on waterbird migrating in Liaoling Shuangtaihekou Natural Reserve. In: Waterbird Specialist Group of Chinese Ornithological Association (eds) Waterbird Research in China. East China Normal University Press, Shanghai, pp 141–146. (in Chinese)

|

|

Williams MD, Bakewell DN, Carey GJ, Xu W, Jin L. 1991. Migration of cranes at Beidaihe Beach, Hebei Province, China. In: Harris J (ed) Proc. 1987 International Crane Workshop. International Crane Foundation, Baraboo, Wisconsin, pp 139–147.

|

| Year | First day seen in spring | Last day seen in fall | Year | First day seen in spring | Last day seen in fall | |

| 1991 | Mar2 | Nov 3 | 2002 | Mar 3 | Nov 14 | |

| 1992 | Mar 4 | Nov 2 | 2003 | Mar 2 | Nov 5 | |

| 1993 | Feb 27 | Oct 28 | 2004 | Feb 26 | Nov 9 | |

| 1994 | Mar 5 | Nov 7 | 2005 | Mar 3 | Nov 5 | |

| 1995 | Mar 3 | Oct 27 | 2006 | Mar 2 | Nov 8 | |

| 1996 | Feb 28 | Nov 9 | 2007 | Feb 28 | Nov 4 | |

| 1997 | Mar 1 | Nov 6 | 2008 | Mar 5 | Nov 18 | |

| 1998 | Mar 2 | Nov 13 | 2009 | Mar 1 | Nov 20 | |

| 1999 | Feb 12 | Nov 6 | 2010 | Mar 2 | Dec 21 | |

| 2000 | Feb 26 | Nov 18 | 2011 | Mar 3 | Wintering individuals | |

| 2001 | Feb 28 | Nov 6 | 2012 | Mar 1 |