| Citation: | Canchao YANG, Wei LIANG, Anton ANTONOV, Yan CAI, Bård G. STOKKE, Frode FOSSØY, Arne MOKSNES, Eivin RØSKAFT. 2012: Diversity of parasitic cuckoos and their hosts in China. Avian Research, 3(1): 9-32. DOI: 10.5122/cbirds.2012.0004 |

In this exposé we provide the first review of host use by brood parasitic cuckoos in a multiple-cuckoo system in China, based on our own long-term field data and a compilation of observations obtained from the literature. In total, we found that 11 species of cuckoos utilized altogether 55 host species. These hosts belong to 15 families, in which Sylviidae, Turdidae and Timaliidae account for 22.6%, 20.8% and 17.0% of parasitism records, respectively. The Common Cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) had the widest range of host species, accounting for 45.5% of the total number of parasitized species (25 in 10 families) of all parasitism records and is the most frequent brood parasite in the country. Cuckoo species differed in their egg coloration and the extent of egg polymorphism with most of them, e.g. the Common Cuckoo, the Lesser Cuckoo (C. poliocephalus) and the Plaintive Cuckoo (Cacomantis merulinus) laying well mimetic eggs with respect to their hosts based on human being's visual observations, while others such as the Large Hawk-cuckoo (C. sparverioides), the Himalayan Cuckoo (C. saturatus) and the Asian Emerald Cuckoo (Chrysococcyx maculatus) usually laid non-mimetic eggs. The use of cuckoo hosts and egg color variation in China are compared with those in other parts of their ranges in Asia.

Avian migration is a spectacular phenomenon that has fascinated humans for centuries. However, many aspects of avian migration biology and particularly of navigation still remain unresolved (Alerstam, 2006). Billions of birds annually move between their breeding and non-breeding areas and many of them show remarkable natal, breeding and wintering site fidelity (Sokolov, 1997; Newton, 2008). To do this, they obviously have to be able to select and maintain flight directions (i.e. to perform migratory orientation) and to find the goal of their movements without any direct sensory contact (i.e. to navigate).

Migrating birds are able to use an array of compass cues for orientation and complex interactions between different cues apparently exist. In recent years, significant advances have been made in understanding compass mechanisms that migrating birds use to determine and maintain direction of their movements (for a review see Wiltschko and Wiltschko, 2009). Particularly, considerable progress has been achieved in understanding the physiological basis of magnetoreception. The birds seem to possess two independent magnetoreception systems, one in their upper beak (Fleissner et al., 2003, 2007; Falkenberg et al., 2010) and one in the retina of their eye (Mouritsen et al., 2004; Mouritsen and Ritz, 2005; Ritz et al., 2010). Only the system localized in the retina is used as a compass, whereas the upper beak magnetoreceptor is not necessary for orientation (Zapka et al., 2009) and might be responsible for the magnetic map sense. The compass system of migrating birds is apparently redundant, i.e. they use several different compass cues, including celestial, magnetic and possibly also olfactory ones and somehow integrate information that they obtain from these cues. How exactly migrants integrate these cues, how and when they calibrate them and which compass system has priority over others is a subject of debate.

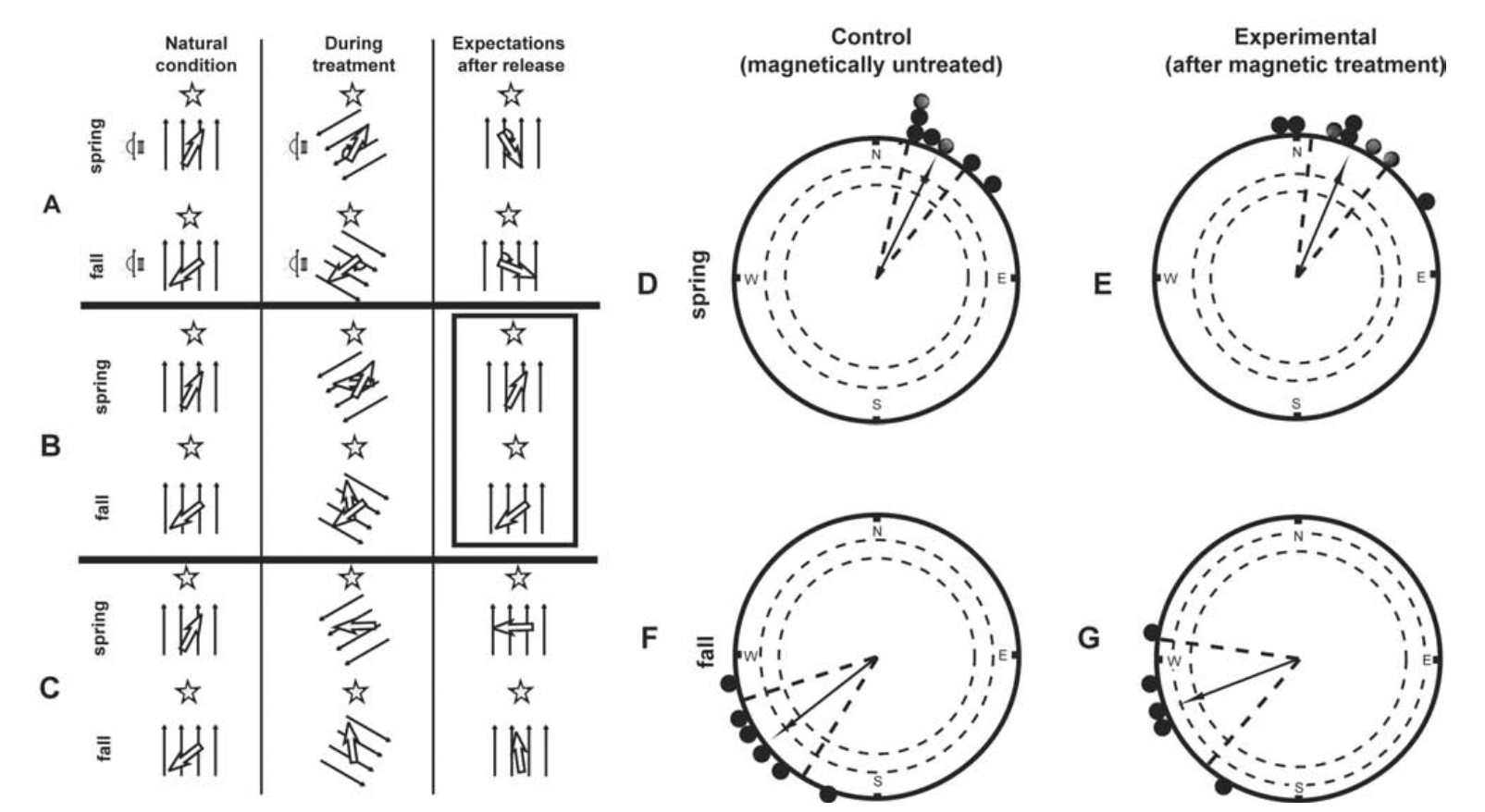

It has been suggested that the relative importance of celestial and magnetic cues varies between the pre-migratory and migratory periods (Wiltschko et al., 1998a, 1998b; Wiltschko and Wiltschko, 1999). During the pre-migratory period, celestial cues provide birds with their primary calibration reference; the magnetic compass is recalibrated when birds are exposed to a rotating magnetic field in the presence of natural celestial cues (Prinz and Wiltschko, 1992; Weindler and Liepa, 1999). Conversely, in most experiments during migration, birds exposed to a rotating magnetic field showed a corresponding shift in the direction of migratory orientation, indicating a precedence of magnetic cues (Wiltschko et al., 1998b, 1999; Sandberg et al., 2000). When tested for after-effects under natural celestial cues in the absence of magnetic cues (vertical magnetic field), the birds maintained the shifted direction, suggesting recalibration of their celestial compass relative to the magnetic field (Bingman and Wiltschko, 1988; Wiltschko et al., 1998b, 1999, 2001; Sandberg et al., 1991, 2000). In the study by Åkesson et al. (2002), juvenile White-crowned Sparrows (Zonotrichia leucophrys gambelii) showed orientation following the rotation of the magnetic field (90° counterclockwise) even when tested in the natural magnetic field (not in the vertical magnetic field) after exposure to cue-conflict, which did not occur at sunset in that study.

The only study that contradicted this apparently coherent pattern was that by Able and Able (1995), who showed that both first-autumn and adult Savannah Sparrows (Passerculus sandwichensis) adjusted their migratory direction as if they were calibrating their magnetic compass relative to celestial cues, not vice versa, as in other studies.

However, more recently Muheim et al. (2006a) reviewed a large body of evidence and detected another pattern. These authors found that responses to cue conflict, either before the onset of migration or during migration, were correlated with access to celestial cues. Birds exposed to cue conflict during sunset used sunset information as the primary cue if they had an unobstructed view of the entire sky, including its part near the horizon. Conversely, if cue conflict experiments were conducted at times of day that did not include sunset or the sky could not be seen near the horizon, the birds would use the geomagnetic field as their primary compass cue. It should be noted that the importance of seeing the sky near the horizon for the correct use of celestial cues had been suggested by Sandberg (1991) much earlier than the publication of the review by Muheim et al. (2006a).

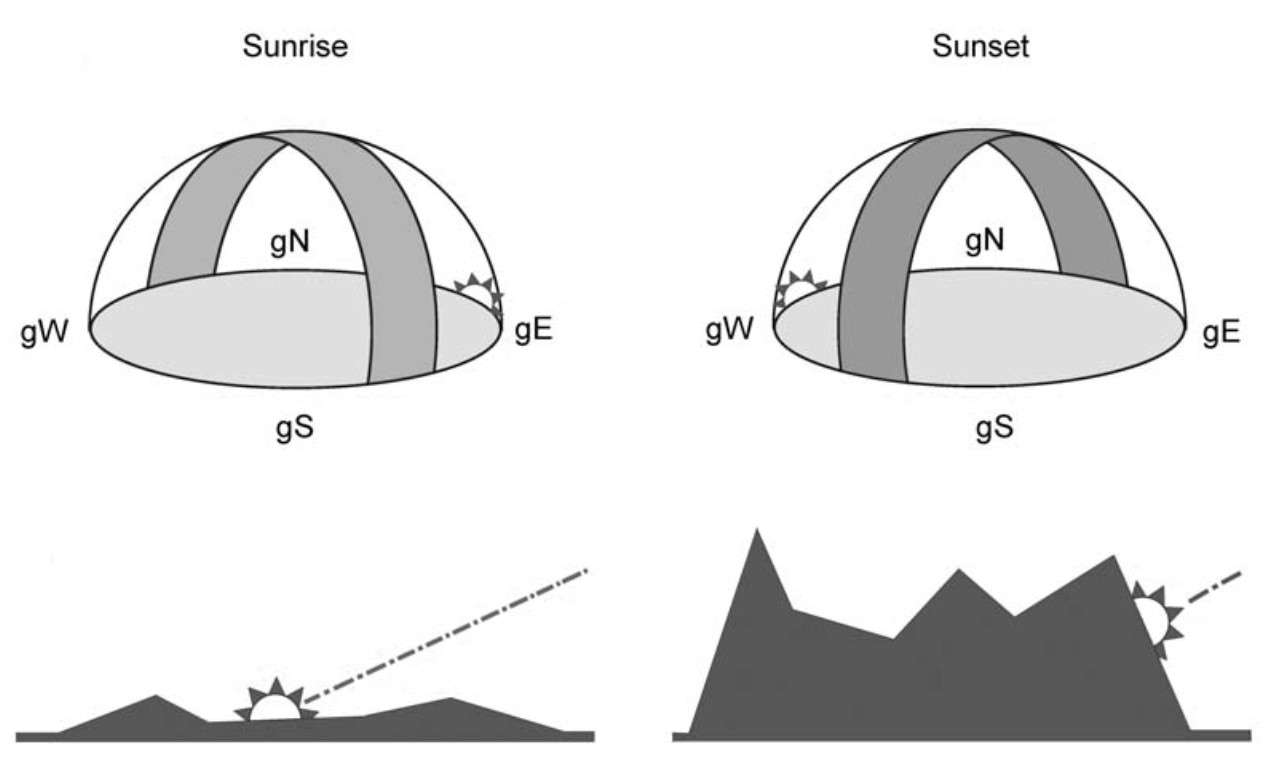

The authors of this review suggested that polarized light cues at sunset, SS (and possibly also at sunrise, SR) were essential for magnetic compass recalibration. However, it should be kept in mind that birds do actually not need to see the SS (or SR) point to be able to deduce their position from the sunlight polarization pattern. At SS and SR, the band of maximum polarization (BMP) passes directly through the zenith and, along with the electrical vector of polarized light, is aligned vertically to the horizon (Fig. 1). In contrast to the position of a sunset point, the intersections of the BMP with the horizon at SS and SR are independent of topography. Moreover, partial view of the sky should be sufficient for deducing the SS point from the BMP at sunset or sunrise.

Muheim et al. (2006b, 2007) conducted their cue-conflict experiments in Emlen funnels (Emlen and Emlen, 1966) using wild-caught Savannah Sparrows to test whether these birds recalibrated their magnetic compass relative to the skylight polarization cues. The authors suggested that migrants averaged directional information obtained from skylight polarization patterns at SS and SR to derive a geographic directional system that provides the primary calibration reference for all of the compasses of migratory songbirds (Muheim et al., 2006b). Averaging the directions of SS and SR is an inviting opportunity indeed, because the bisector of the directions towards the SS and SR points is the north-south axis, 365 days a year in any location on the earth. However, the results of Muheim et al. (2006b) do not actually provide evidence for averaging directional information from skylight polarization patterns at SS and SR. The birds shifted their orientation by 90° after being exposed to polarization patterns shifted by 90°, which means that they did not average their orientation, for otherwise the directional shift by the birds should have been 45°, not 90° (as shown by Bill Cochran in a discussion at the RIN Animal Navigation Forum in September 2006).

Another problem, emphasized by Wiltschko et al. (2008a), is that it is not at all clear whether the Savannah Sparrows, tested by Muheim et al. (2007), were in the migratory disposition in the first place. Neither was the initial distribution of the headings of the birds shown nor was a mean vector given. The sample from which the test birds were selected may not have been oriented towards their migratory direction. The authors selected individuals that oriented to the southeast (the assumed migratory direction) ±90° for further testing. This is a quite problematic procedure, because the birds taken from a sample which is not significantly oriented cannot be assumed to be oriented even if their headings per chance lie in the migratory direction. A second test before exposure to check whether the birds truly headed in their migratory direction was not reported. Therefore, it is not immediately obvious whether the behavior of the birds in this experiment was at all migratory.

Wiltschko et al. (2008a) obtained contradictory results when testing Australian Silvereyes (Zosterops lateralis) in Emlen funnels. Their birds paid no attention to cue conflict and maintained the same seasonally appropriate migratory direction both before and after exposure. Unlike Muheim et al. (2007) who altered polarization pattern by using polarizers (which is extremely difficult to do in a fashion similar to the natural pattern), Wiltschko et al. (2008a) rotated the magnetic field by Helmholtz coils and let the birds see the naturally polarized sky. Muheim et al. (2008) explained the discrepancy between their results (Muheim et al., 2006b, 2007) and those by Wiltschko et al. (2008a) by the fact that the Australian Silvereyes tested in the latter study could have calibrated migratory compass direction on landmarks they could see in the aviary. However, it is not immediately clear why, if silvereyes in Australia did it as suggested by Muheim et al. (2008), Savannah Sparrows in Alaska studied by Muheim et al. (2006b, 2007) failed to do the same. Summarizing, the claim that Savannah Sparrows calibrated their magnetic compass on skylight polarization cues and, especially that they averaged directions from both SS and SR, seems less than convincing.

It should be however noted that in later experiments with White-throated Sparrows (Zonotrichia albicollis) Muheim et al. (2009) rotated the magnetic field, similar to Wiltschko et al. (2008a) and obtained the same results (priority of skylight polarization compass) as were recorded for Savannah Sparrows (Muheim et al., 2006b, 2007). Furthermore, White-throated Sparrows tested in spring and in autumn (Muheim et al., 2009) undoubtedly were on migration. Generally, in the latter study the authors addressed some of the concerns voiced by Wiltschko et al. (2008a, 2008b) and their results look more convincing than the results of their earlier work with Savannah Sparrows (Muheim et al., 2006b, 2007).

Like Wiltschko et al. (2008a), Gaggini et al. (2010) reported that Pied Flycatchers (Ficedula hypoleuca) did not calibrate their magnetic compass on sunset cues during spring migration in Italy. However, their study is problematic in the same manner as the study by Muheim et al. (2007): the initial sample of untreated birds captured during the spring migration was not significantly oriented in the migratory direction (Fig. 4a in Gaggini et al., 2010). All birds in the Italian study were, beyond doubt, on migration but since they were tested within several days after capture, their behavior may have reflected stress responses rather than migratory direction. Freshly captured migrants, unlike individuals that are given time to get accustomed to captivity, are known often to show phototactic or other stress responses (Marchetti and Baldaccini, 2003). If the birds do not show a meaningful migratory orientation in the first place, all further cue-conflict experiments with them are necessarily problematic.

In another study performed during autumn migration in Denmark, Pied Flycatchers and Redstarts (Phoenicurus phoenicurus) did not calibrate their magnetic compass from sunset cues (Rabøl, 2010). Their orientation in Emlen funnels during the deep night was not affected by pre-exposure to a horizontally rotated geomagnetic field.

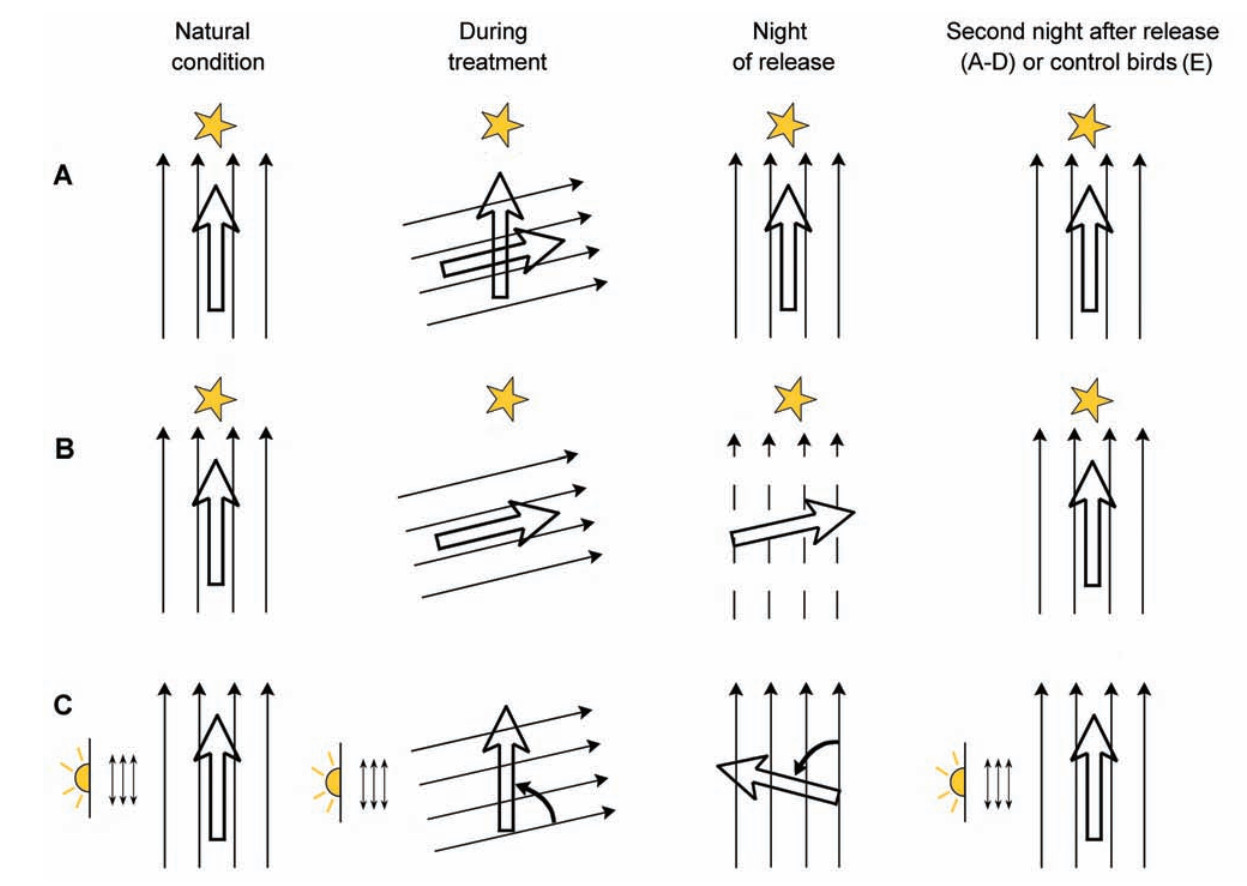

The study by Cochran et al. (2004) very convincingly showed that the Gray-cheeked Thrush (Catharus minimus) and Swainson's Thrush (C. ustulatus) indeed infer compass direction from sunset cues before take-off and maintain it during nocturnal migratory flight on the basis of their magnetic compass. In this study migrants were not tested in Emlen funnels but were radio-tagged and tracked when flying by natural nocturnal migratory flight. At twilight, these two species of Catharus thrushes were exposed to an artificial magnetic field that was identical to the natural geomagnetic field, but rotated 80° clockwise (Fig. 2). When the birds where released, they immediately found themselves in the natural unaltered magnetic field and flew generally 80° counterclockwise of their normal migratory direction. During the next night, their migratory direction was back to normal, suggesting that compass recalibration occurs every day (Fig. 2). The study by Cochran et al. (2004) is a very convincing one and very clean methodologically. It is difficult to agree with the criticism by Wiltschko et al. (2008a) who claimed that this study is problematic since the birds were free-flying rather than confined to an Emlen funnel. In our opinion, this is a very strong feature of this study and not its drawback. The suggestion that the thrushes of Cochran et al. could be overcompensating after exposure to cue conflict (Wiltschko et al., 2008) does not hold either because, as correctly emphasized by Muheim et al. (2008), these birds showed deflected orientation when tracked immediately upon release just after cue conflict.

However, a recent study by Chernetsov et al. (2011) aimed to repeat the work of Cochran et al. (2004) in a European medium-distance migrant, the Song Thrush (Turdus philomelos). It was also based on tracking free-flying birds, with the difference that Chernetsov et al. (2011) did not follow the released radio-tagged birds by car, but just recorded their vanishing directions at least 15 km after their nocturnal migratory take-off. Song Thrushes in this study did not calibrate their compass systems, but showed a simple domination of either a magnetic or possibly a stellar compass, as suggested by the lack of any effect of magnetic field horizontal rotation prior to release on their flight directions (Fig. 3).

The studies by Cochran et al. (2004) and Muheim et al. (2006b, 2007, 2009) impressed the avian orientation community greatly and many authors quickly forgot previous results, suggesting the primary role of the magnetic compass (see above). A reason to discard this information was that tracking of free-flying migrants is considered methodologically superior to Emlen funnel tests that, even though broadly used in avian orientation research, still represent a highly unnatural and probably stressful situation for migrants. However, some results suggesting recalibration of celestial cues by magnetic compass were obtained by release experiments, not in Emlen funnels (e.g. Sandberg et al., 2000). Therefore we argue that the very impressive results by Cochran et al. (2004) and Muheim et al. (2006b), providing strong evidence that the two Catharus thrushes and probably Savannah and White-throated Sparrows used skylight polarization pattern as their primary compass cue and regularly recalibrate their magnetic compass on it, should not be immediately generalized to other avian migrants. Even if we believe that the results of Gaggini (2010) suggesting no cue calibration are questionable, we still have the results by Wiltschko et al. (2008a) and Rabøl (2010) obtained by Emlen funnel testing and, rather more importantly, the results from Chernetsov et al. (2011) from free-flying Song Thrushes suggest that some nocturnal migrants do not calibrate compass cues but rely on simple domination.

It has been suggested by Susanne Åkesson during her talk at the 7th Royal Institute of Navigation 2011 conference "Orientation and Navigation. Birds, Humans and Other Animals" in Reading, UK, that among-species variation observed might be explained by the necessity to cross areas with broadly varying declination values (declination is the angular difference between the magnetic North and the geographic North) in long-distance North American passerine migrants, whereas European migrants and Australian Silvereyes may not face this challenge and remain within the zones with similar inclination values throughout their annual cycle. Another non-excluding possibility mentioned by Chernetsov et al. (2011) is that long-distance migrants generally need a capacity for more precise orientation, whereas short- and medium-distance migrants (e.g. Australian Silvereyes and Song Thrushes) may tolerate larger angular deviations from their inherited compass migratory directions.

We are particularly thankful to all the bird watching enthusiasts who offered photographs of cuckoos and their hosts. We thank Jeremy Wilson, the editor of Ibis, Andrew MacColl, associate editor of Ibis and two anonymous referees of Ibis for providing helpful comments on this manuscript. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31071938, 31101646), Key Project of Chinese Ministry of Education (No. 212136), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation funded project (20110490967) and the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-10-0111). We thank the Forestry Department of Guizhou Province and the Kuankuoshui National Nature Reserve for support and permission to carry out this study, as well as X. Guo, L. Wang, X. Xu, N. Wang and T. Su for assistance with the field work.

|

Ali S, Ripley SD. 1974. Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan, Together with Those of Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan and Ceylon. Oxford University Press, Bombay.

|

|

Baker ECS. 1906. The oology of Indian parasitic cuckoos (Part II). J Bombay Nat His Soc, 17: 351–374.

|

|

Baker ECS. 1907. Additional cuckoo notes. J Bombay Nat His Soc, 17: 876–894.

|

|

Baker ECS. 1919. Some notes on the genus Surniculus. Novitates Zool, 26: 291–294.

|

|

Baker ECS. 1927. The Fauna of British India Including Ceylon and Burma. Taylor and Francis, Longdon.

|

|

Baker ECS. 1934. The Identification of Birds of the Indian Empire. Taylor and Francis, London.

|

|

Baker ECS. 1942. Cuckoo Problems. H. F. and G. Witherby, London.

|

|

Becking JH. 1981. Notes on the breeding of Indian cuckoos. J Bombay Nat His Soc, 78: 201–231.

|

|

Bu F, Zhang L, Ren B. 1999. Breeding ecology of Indian Cuckoo in Xiaodian area of Taiyuan city, Shanxi Province. Shanxi Forest Sci Technol, 3: 36–38. (in Chinese)

|

|

Carey GJ, Chalmers ML, Diskin DA, Kennerley PR, Leader PJ, Leven MR, Lewthwaite RW, Melville DS, Turnbull M, Young L. 2001. The Aviafauna of HongKong. Hong Kong Bird Watching Society, Hong Kong.

|

|

Cheng TS, Xian Y, Guan G. 1991. Fauna Sinica: Aves, Columbiformes, Psittaciformes, Cuculiformes and Strigiformes. Science Press, Beijing. (in Chinese)

|

|

Cheng TS. 1963. Resource fauna of China. Aves. Beijing: Science Press. (in Chinese)

|

|

Cheng TS. 1973. Avifauna of Qingling Mountain. Science Press, Beijing. (in Chinese)

|

|

Fan L, Liu R, Song Q. 2000. Breeding ecology of Large-Hawk cuckoo in Lishan Nature Reserve, Shanxi Province. Sichuan J Zool, 19: 85–86. (in Chinese)

|

|

Fu T, Gao W, Song Y. 1984. Birds of Changbai Mountain. Northeastern China Normal University Press, Jilin. (in Chinese)

|

|

Gao W. 2004. The Ecology of Cavity-nesting Birds of Northeastern China. Jilin Science and Technology Press, Jilin. (in Chinese)

|

|

Gao W, Yang Z, Luo W. 1990. Observation on breeding behavior of three bird species. Chinese Wildl, 4: 10–11. (in Chinese)

|

|

Guangdong Institute of Entomology, Sun Yat-sen University. 1983. Birds and Mammals of Hainan Island. Science Press, Beijing. (in Chinese)

|

|

Hao S, Wang Y. 1992. Breeding ecology of the Oriental Reed Warbler. Shandong Forest Sci Technol, 1: 20–22. (in Chinese)

|

|

Harrison CJO. 1969. The identification of the eggs of the smaller Indian cuckoos. J Bombay Nat His Soc, 66: 478–488.

|

|

Hellebrekers WPJ, Hoogerwerf A. 1967. A further contribution to our oological knowledge of the island of Java (Indonesia). Zool Verhand, 88: 1–164.

|

|

Higuchi H. 1989. Responses of the bush warbler Cettia diphone to aritifical eggs of Cuculus cuckoos in Japan. Ibis, 131: 94–98.

|

|

Higuchi H. 1998. Host use and egg color of Japanese cuckoos. In: Rothstein SI, Robinson SK (eds) Parasitic Birds and Their Hosts: Studies in Coevolution. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 80–93.

|

|

Hoogerwerf A. 1949. Bijdrage tot de Oölogie van Java. Limosa, 22: 1–279.

|

|

Hornskov J. 1995. Recent observations of birds in the Philippine Archipelago. Forktail, 11: 1–10.

|

|

Hume AO. 1873. Nest and Eggs of Indian Birds, Rough Draft. Office of Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta.

|

|

Jia C, Liang W, Gong H. 2007. Chestnut-winged Cuckoo parasitized the Hwamei. Chinese J Zool, 42: 38. (in Chinese)

|

|

Jiang Y, Liang W, Yang C, Sun Y. 2006. Lesser Cuckoo parasitized the Brownish-flanked Bush Warbler. Chinese J Zool, 5: 31. (in Chinese)

|

|

Jiang Y, Liang W, Yang C, Sun Y. 2007. Large Hawk-cuckoo parasitized the White-browed Laughingthrush. Sichuan J Zool, 26: 509. (in Chinese)

|

|

La Touche JDD. 1931-34. A Handbook of the Birds of Eastern China. Taylor and Francis, London.

|

|

Lewthwaite RW. 1996. Forest Birds of Southeastern China: Observations during 1984–1996. Hong Kong Bird Report, Hong Kong.

|

|

Li G. 1985. Fauna of Sichuan Province. Vol. 3: Birds. Sichuan Science and Technology Press, Chengdu. (in Chinese)

|

|

Lin RX. 2008. Observation of Oriental Cuckoo parasitism on Rufous-capped Babbler in central Taiwan. Nat Conserv Q, 64: 58–62. (in Chinese)

|

|

Liu H, Feng J, Su H. 1984. Observation on egg-laying of the common cuckoo. Sichuan J Zool, 3: 14–16. (in Chinese)

|

|

Liu H, Su H, Shen S, Lan Y, Ren J, Wu W. 1988. Breeding ecology of the Eurasian Wren in Guandi Mountain, Shanxi Province. Chinese J Zool, 23: 8–12. (in Chinese)

|

|

Liu X, Long G. 1986. Breeding behavior of the Light-vented Bulbul. Chinese J Zool, 5: 12–15. (in Chinese)

|

|

Lu X. 1988. Common cuckoo parasitism on the oriental reed warbler. Sichuan J Zool, 7: 21–22. (in Chinese)

|

|

Mackenzie JMD. 1918. Some further notes on cuckoos in Maymyo. J Bombay Nat His Soc, 25: 742–745.

|

|

MacKinnon J, Phillipps K. 1999. A Field Guide to the Birds of China. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

|

|

Nakamura H, Kubota S, Suzuki R. 1998. Coevolution between the common cuckoo and its major hosts in Japan. In: Rothstein SI, Robinson SK (eds) Parasitic Birds and Their Hosts: Studies in Coevolution. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 94–112.

|

|

Neufeldt I. 1971. Der Kurzflügelsänger Horeites diphone (Kittlitz). Falke, 18: 364–375.

|

|

Osmaston AE. 1912. Eggs of the large hawk-cuckoo (Hierococcyx sparverioides). J Bombay Nat His Soc, 21: 1330–1331.

|

|

Osmaston BB. 1916. Notes on cuckoos in Maymyo. J Bombay Nat His Soc, 24: 359–363.

|

|

Payne RB. 2005. The Cuckoos. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

|

|

Qian Y, Zhang J. 1965. Birds and Mammals of Southern Xinjiang. Science Press, Beijing. (in Chinese)

|

|

Rothstein SI, Robinson SK. 1998. Parasitic Birds and Their Hosts: Studies in Coevolution. Oxford University Press, New York.

|

|

Sheldon FH, Moyle RG, Kennard J. 2001. Ornithology of Sabah: history, gazetteer, annotated checklist, and bibliography. Ornithol Monogr, 52: 1–285.

|

|

Smythies BE. 1957. An annotated checklist of the birds of Borneo. Sarawak Museum J, 9: 523–818.

|

|

Smythies BE. 1999. The Birds of Borneo. 4th edn. Natural History Publications, Kota Kinabalu.

|

|

Stevens H. 1925. Notes on the birds of the Sikkim Himalayans. J Bombay Nat His Soc, 30: 664–685.

|

|

Tian F, Song Y, Hao S, Feng Z, Wang Y. 1991. Notes on ecology of the common cuckoo in Nansi Lake. Shandong Forest Sci Technol, 1: 9–12. (in Chinese)

|

|

Vaughan RE, Jones KH. 1913. The Birds of Hong Kong, Macao and the West River or Si Kiang in South-East China, with special reference to their identification and seasonal movements. Ibis, 10: 17–384.

|

|

Wang H, Jiang Y, Gao W. 2011. Jankowski's bunting (Emberiza jankowskii): current status and conservation. Chinese Birds, 1: 251–258.

|

|

Wang Z, Jia C, Sun Y. 2004. Parasitized breeding and nestling growth in oriental cuckoo. Chinese J Zool, 39: 103–105. (in Chinese)

|

|

Wells DR. 1999. The Birds of the Thai-Malay Peninsula. Vol. 1, Non-passerines. Academic Press, New York.

|

|

Yan A. 1985. Observation on Indian Cuckoo. Chinese Bull Biol, 3: 13. (in Chinese)

|

|

Yang C, Cai Y, Liang W. 2008. Asian Emerald Cuckoo parasitized the Bianchi's Warbler Seicercus valentini. Chinese J Zool, 43: 74–75. (in Chinese)

|

|

Yang C, Cai Y, Liang W. 2010a. Brood parasitism and egg mimicry on brownish-flanked bush warbler (Cettia fortipes) by lesser cuckoo (Cuculus poliocephalus). Zool Res, 31: 555–560. (in Chinese)

|

|

Yang C, Cai Y, Liang W. 2011. Visual modeling reveals cryptic aspect in egg mimicry of Himalayan Cuckoo (Cuculus saturatus) on its host Blyth's Leaf Warbler (Phylloscopus reguloides). Zool Res, 32: 451–455.

|

|

Yoon MB. 2000. Wild Birds of Korea. Kyo-Hak, Seoul.

|

|

Zhang J. 2001. Observation on the breeding habits of Dicrurus macrocercus. Chinese J Zool, 36: 60–63. (in Chinese)

|

|

Zhang T. 1989. Studies on breeding ecology of the common cuckoo. Shandong Forest Sci Technol, 1: 24–26. (in Chinese)

|

|

Zhang W. 1980. A Field Guide to the Birds of Taiwan. Insititue of Environmental Science, Tunghai University, Taiwan. (in Chinese)

|

|

Zhao Z, He J. 1981. Studies on the breeding biology of blue-and-white flycatcher. Acta Zool Sin, 27: 388–394. (in Chinese)

|

|

Zhao Z. 1985. The Avifauna of Changbai Mountain. Jilin Science and Technology Press, Jilin. (in Chinese)

|

|

Zheng G. 2011. A Checklist on the Classification and Distribution of the Birds of China. 2nd edn. Science Press, Beijing.

|

|

Zhou L, Song Y, Ma Y. 2001. Studies on breeding ecology of the balckbird. Chinese J Ecol, 20: 32–34. (in Chinese)

|