| Citation: | Johann H. VAN NIEKERK. 2011: Observations of Red-billed Spurfowl (Pternistis adspersus) in the arid Molopo Nature Reserve, North West Province, South Africa. Avian Research, 2(3): 117-124. DOI: 10.5122/cbirds.2011.0023 |

Field work was conducted in the southern half of the Molopo Nature Reserve (MNR) near Vostershoop in the North West Province of South Africa to (1) describe the past and present distribution of Red-billed Spurfowl (Pternistis adspersus) in South Africa and (2) to describe the dispersion of Red-billed Spurfowl at waterholes in the MNR. The Red-billed Spurfowl did not colonize this area from Botswana in the 1990s as reported in Hockey et al. (2005) and their distribution status and population sizes are not determined by long distance (30–100 km) and/or seasonal movements between the two countries. Red-billed Spurfowl are sparsely distributed and mainly occur in clusters near man-made waterholes. Waterholes provide water and food found in and around antelope droppings. The movement of the Red-billed Spurfowl between waterholes over short distances of 2–5 km was probably encouraged by the sinking of more boreholes since the 1980s (and the creation of 'veeposte' (game/livestock camps) around them). Low rainfall that results in limited insects is probably the single most important factor limiting populations of the Red-billed Spurfowl in South Africa.

How does a resident terrestrial gamebird species such as the Red-billed Spurfowl (Pternistis adspersus) survive at low population densities in an arid environment with limited food and water? Red-billed Spurfowl and specifically their dependence on waterholes in the Kalahari, has received very little scientific scrutiny. According to Milstein and Wollf (1987), this spurfowl was displaced by the Natal Spurfowl (P. natalensis) in a westerly direction from the Molopo and Limpopo River valleys during the 1900s. Presently, Red-billed Spurfowl occur north of Kuruman in the Kalahari region but was reportedly absent here during the mid 1980s (Hockey et al., 2005). Most published information on this species focussed on density and distribution (Hockey et al., 2005), while aspects of its general biology has been described by Little and Crowe (2011) and Madge and McGowan (2002). van Niekerk (2009) described hybridisation between Red-necked P. afer and Natal Spurfowls in captivity. The purposes of this study are (1) to describe the past and present distribution of Red-billed Spurfowl in South Africa and (2) the dispersion of Red-billed Spurfowl at waterholes in the Molopo Nature Rerve.

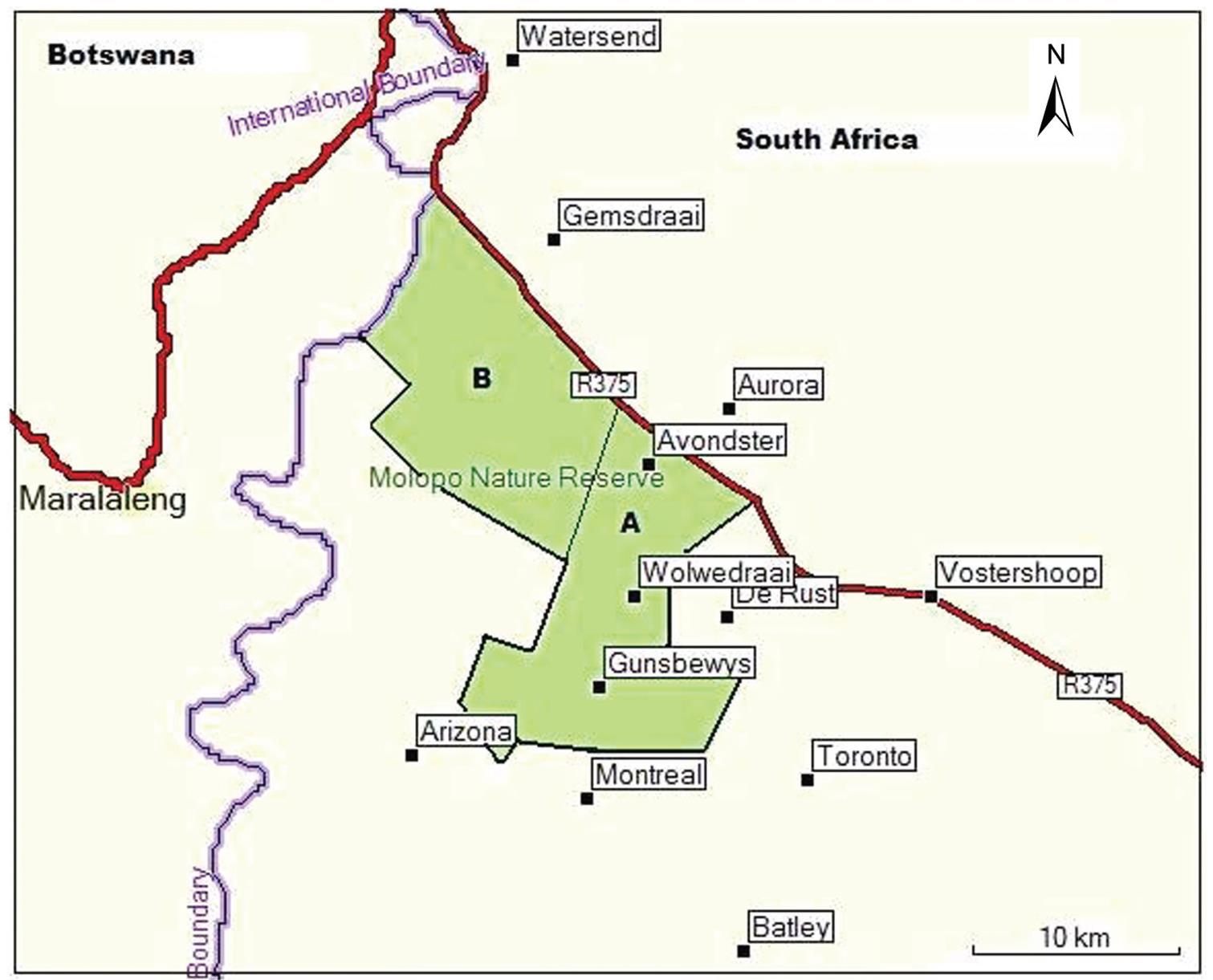

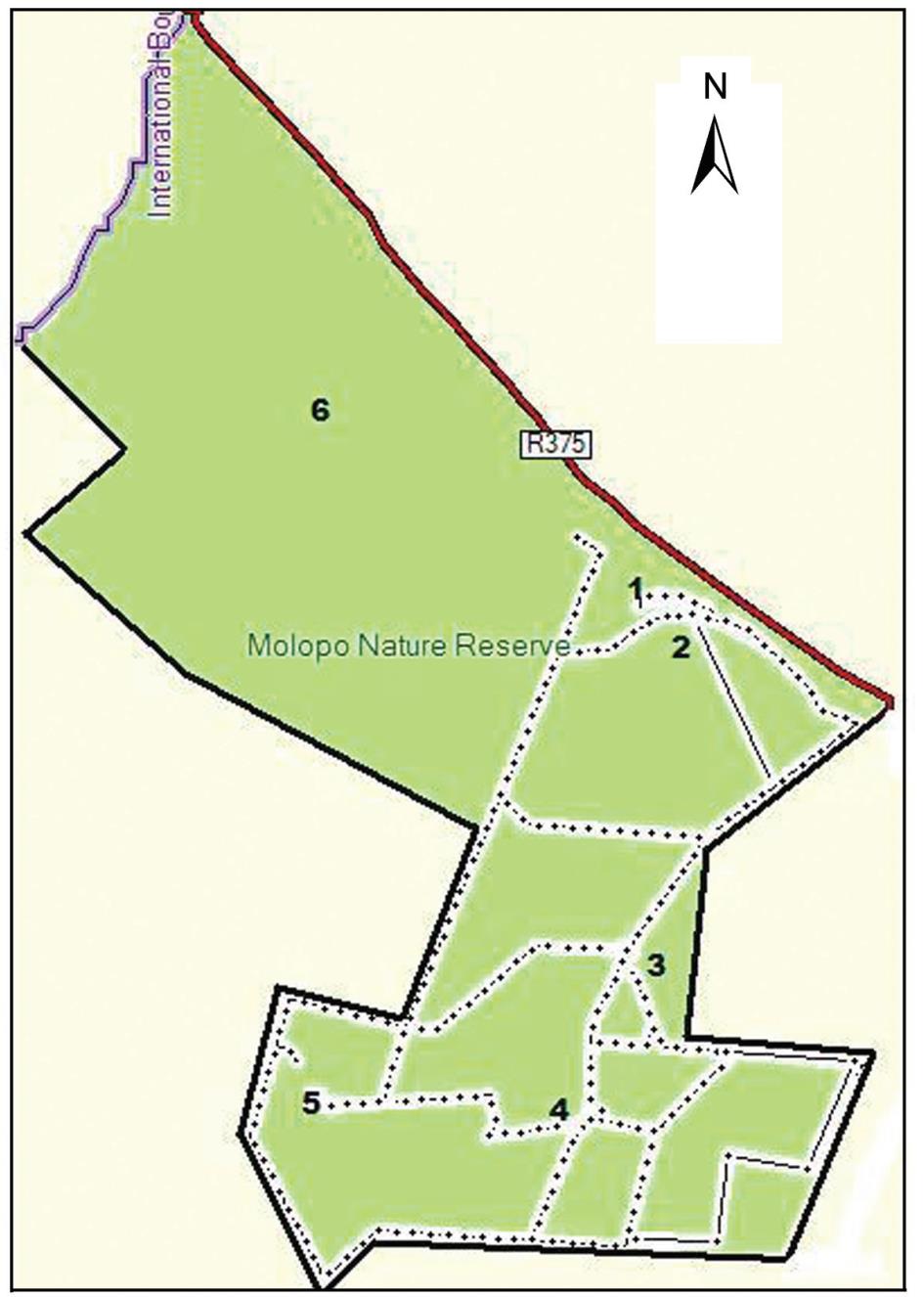

Field work was conducted in the southern half of the Molopo Nature Reserve (MNR) (25°47′S, 22°56′E; 1000 m above sea level) near Vostershoop in the north western corner of the North West Province of South Africa (Fig. 1). The reserve covers a total area of about 240 km2 of which about 120 km2 was traversed regularly for observations (Fig. 2A). The Molopo River forms part of the international border between Botswana and the reserve. This Kalahari semi-desert area is characterized by extreme temperatures and arid winters. The reserve receives an annual rainfall of about 332 mm that mainly falls in summer (Meyer et al., 2007). The mean annual temperature is 19.1℃ (Mucina and Rutherford, 2006). A temperature log meter (ThermaData Logger), set up in the reserve, revealed a temperature range from −7–25℃ in June 2010 (winter) and 18–35℃ in February 2011 (summer). The vegetation is described as Molopo Bushveld, which is open woodland to closed shrubland, dominated by Acacia and Boscia tree species, with grass cover broken by patches of open sand (Mucina and Rutherford, 2006). The soils are mainly deep and red, with sand dunes closer to the drainage valleys such as the Molopo River.

Wolwedraai and Gunsbewys waterholes formed the focus of this study (Fig. 2). These sites were 3.8 km apart and were the nodal points where two sub-populations existed throughout the survey and for at least nine years previously (G. Botha, pers. comm.). Wolwedraai is a camp site, where about 5–10 staff members have lived in separate dormitories since 1975, with open water troughs nearby for game, while Gunsbewys is only a borehole and waterhole where antelopes come to drink on a daily basis. At Gunsbewys, spurfowl scratched actively in antelope droppings for seeds and insects, especially in the moist sand (due to urine) underneath them (cf. Hockey et al., 2005).

The reserve was visited for four five-day surveys during April 2009, December 2009, June 2010 and February 2011. Three game wardens, 12 landowners and three farm employees around the reserve were interviewed to determine past and present distribution and group sizes of Red-billed Spurfowl (Fig. 2, Table 1). A 50%-life-size color photograph of the spurfowl was used to distinguish it from the Orange River Francolin (Scleroptila levaillantoides) and sandgrouse (Pterocles spp.) that also occur in the area.

| Farm name/locality | Respondent/warden | Group size | Earliest date observed | Comments |

| Gemsdraai | R. Boshof | Two groups totalling about 12 spurfowl | Since farmer's arrival on farm 4 years ago. | Occur around farm house. Permanent residents. |

| Toranto | H. Burger | 6–10 spurfowl in at least two groups | Since farmer's arrival 7 years ago. | Occur around farm house. Permanent residents. |

| Batley | W. Jones | 3–4 spurfowl | Observed for last 25 years since his arrival. | Foraged in small maize fields. Permanent residents. |

| Vostershoop shop | J. Strydom | 5–6 spurfowl | Observed daily at shop during 2008–2009 but disappeared since. | Fed on grains given to chickens daily. |

| Watersend | J. Holtshauzen | 6–7 spurfowl | Since farmer's arrival 21 years ago. | Covey with chicks around house in January 2011. Permanent residents. |

| De Rust | W. Harvey | Groups of 2–3 around the house | Since first noticed about 30 years ago. | Permanent residents |

| Arizona | J. Olyn | Two groups of about 3 each | Observed since his arrival in 1999 around veeposte. | Permanent resident. Hens produce up to 6 and more chicks. |

| Gunsbewys (MNR) | G. Botha | Sub-population of 6 spurfowl | Since arrival in reserve 9 years ago. | Permanent residents |

| Freddie McDonald's farm | Employee | Seen three on 16 December 2009. | ― | Seen during midday coming to drink water. |

| Vostershoop | N. Voster | Often seen at veeposte where they drink water. Occur in small groups. | Observed since his arrival in 1940. Permanent in area but move locally. | Vostershoop named after his father in 1940. Female produced 6 chicks. |

| Montreal | H. Beyleveld | Small groups of 2–3 spurfowl | Only observed since 1985. | Locally nomadic |

| Number of farms around Vostershoop | H. Mokaadi | Small groups | Since arrival at Vostershoop in 1999. | Observed spurfowl as child in Morokweng during 1960–1966. Permanent residents. |

| Wolwedraai Camp (MNR) | J. Diseko (game warden) | Sub-population of about 10 | Since his arrival 35 years ago. | Spurfowls forage around campsite. Permanent residents. |

| Aurora | C. Ras | No spurfowls observed around house. | Arrived on farm 15 months ago. | ― |

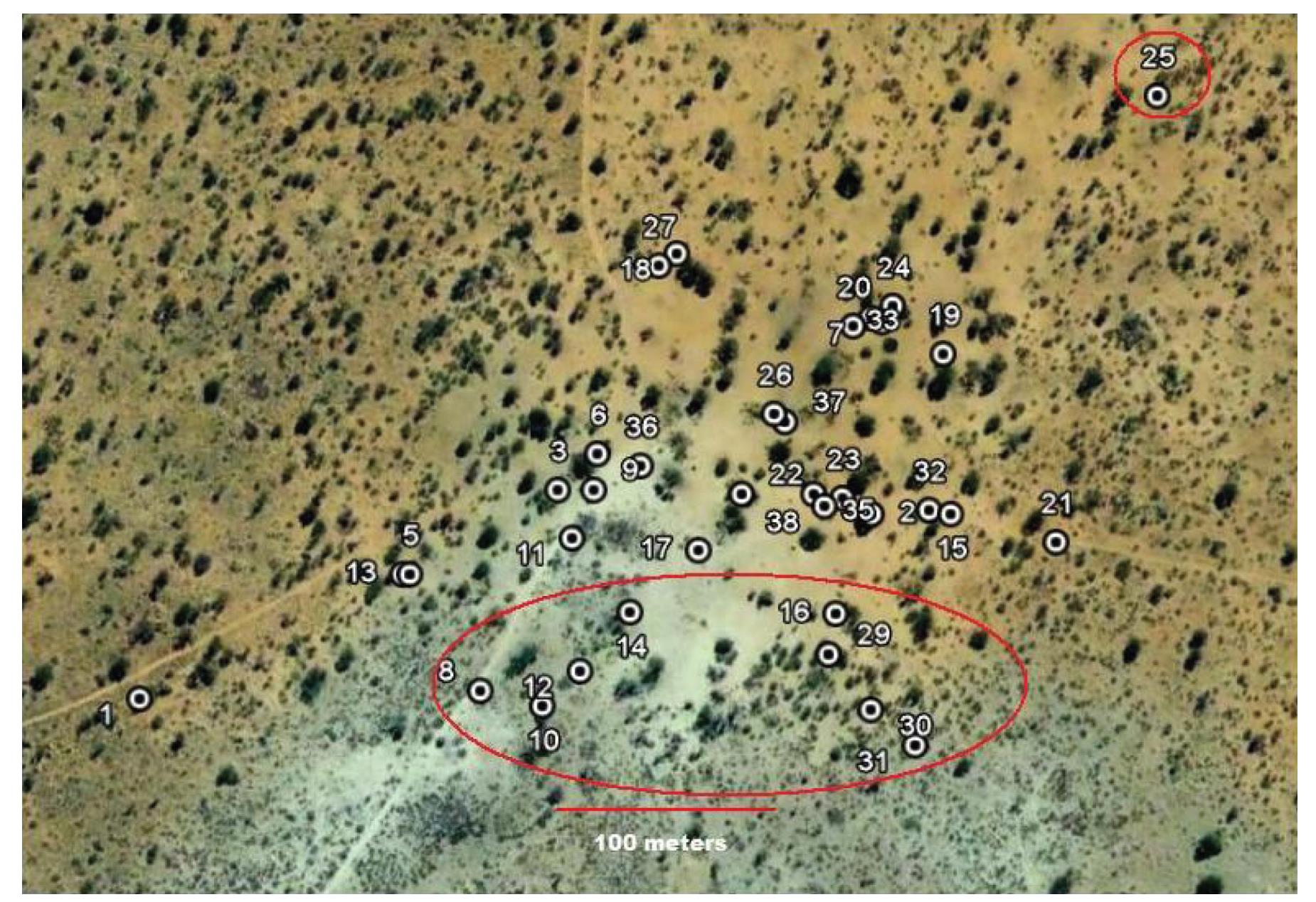

A fixed route was traversed during each survey, covering a total of 2600 km (130 km per day) and totalling 120 h of observations (Fig. 3). Each survey passed by five man-made waterholes fed from underground boreholes (Fig. 3). The position of each spurfowl sighting (single bird/covey) was recorded with a GPS (Global Positioning System, Garmin Colorado 300) and any group size and composition or behavioral aspects were noted. Four sand roads intersected at Gunsbewys waterhole, each road oriented more or less at right angles in four compass directions. This allowed me to walk or travel each road for 500 m from the waterhole in search of fresh tracks and note their location with a GPS (Stuart and Stuart, 2000). All GPS data were printed on maps using the MapSource computer software program. The dispersion areas of the spurfowl sub-populations at Wolwedraai and Gunsbewys respectively were determined by drawing a polygon around all sightings of spurfowls for each site (connecting outermost GPS coordinates, see van Niekerk et al., 2009) (Table 2). Density estimation was based on the dispersion area around the waterhole divided by the mean of the sub-population size (Table 2). Since Red-billed Spurfowl responded vigorously to play-back calls (J.H. van Niekerk, unpublished report), calls were played for about 10–15 times during each survey at Wolwedraai and Gunsbewys waterholes to lure spurfowl into sight or to evoke spurfowl calls in the vicinity. Spurfowls responded to calls from a maximum distance of about 100 m. A Sony (ICD-PX820) tape recorder was used to produce the playback calls.

| Wolwedraai | Gunsbewys | |

| Mean sub-population size | 4.3 (n = 3, SD = 1.52, range = 3–6) | 4.25 (n = 4, SD = 0.95, range = 3–5) |

| Number of coveys observed per hour | 0.33/hour | 0.37/hour |

| Mean group size | 2.14 (n = 14, SD = 0.86, range = 1–4) | 2.15 (n = 20, SD = 0.95 range = 1–5) |

| Dispersion areas of sub-populations (polygon drawn around all sightings including all site visits) | 24 ha | 34 ha |

| Density (dispersion area/mean sub-population size) | 0.179 spurfowl/ha | 0.125 spurfowl/ha |

The Red-billed Spurfowl has been present in and around Vostershoop for at least 70 years, living in small groups of about 2–6 spurfowls per covey (Table 1, Fig. 2). The range of group sizes of spurfowl on outlying farms does not differ substantially from the group sizes that were recorded in the MNR (Tables 1, 2). In other parts of southern Africa, north of the MNR, group sizes of 7–20 have been recorded (Madge and McGowan, 2002; Hockey et al., 2005). Based on interviews with 10 landowners no evidence was found that groups were particularly larger in one area than another and neither were group sizes particularly larger from one year to the next (Table 1).

The population structure of spurfowls in the MNR was deduced from 33 coveys observed at Gunsbewys and Wolwedraai (Fig. 4). Offspring made up 12% of the entire population of 75 spurfowls counted at Wolwedraai and Gunsbewys. The mean group size of broods was 1.8 (SD = 0.83, range = 1–3, n = 5), but only one out of two adult females at a waterhole had offspring. From Table 1 it is evident that females can produce about six chicks but based on the recorded mean brood size, about 70% die off between hatching and sub-adulthood (Hockey et al., 2005).

The spurfowl population within the demarcated research area of the MNR was estimated at 15 individuals (Fig. 2). The mean estimated sub-populations observed at Wolwedraai and Gunsbewys did not differ significantly in size, respectively 4.3 and 4.25 (ANOVA: F = 0.000321, df1,6, p > 0.05) (Table 2). Neither did the mean group sizes at Wolwedraai and Gunsbewys differ significantly (ANOVA: F = 0.000417, df1,32, p > 0.05). The sub-populations found at each site were often split into two coveys. In some cases it was a single female with offspring and a male elsewhere or two pairs. The number of spurfowls observed per hour at Wolwedraai and Gunsbewys were also similar (Table 2).

The use of tracks in the sand at Gunsbewys was useful to determine dispersal areas, although tracks proved unreliable during windy days or after about 5–6 hours as they could not be distinguished satisfactorily from those of the Helmeted Guineafowl (Numida meleagris), the Red-crested Korhaan (Lophotis ruficrista) or the Spotted Thick-knee (Burhinus capensis).

The absence of spurfowls between waterholes and the clustering of spurfowls around waterholes made it possible to determine the dispersion areas of sub-populations without marking any individuals (Komen, 1987). Table 2 shows the dispersion areas of spurfowl at both waterholes during different visits to the MNR. The mean dispersion areas at Wolwedraai and Gunsbewys were not significantly different (ANOVA: F = 0.1130, df2,4, p > 0.05). The density (mean dispersion areas/mean sub-population size) of spurfowl at Wolwedraai and Gunsbewys was also similar (Table 2). Overall, a density of about 0.001 spurfowl/ha (15 spurfowls per 12000 ha) was calculated for the MNR research area.

Spatially, the dispersion pattern at Gunsbewys was loosely characterized by three sub-areas. Dominant males (see below) remained near the waterholes (Fig. 5). Females with offspring moved up and down in a southerly direction between roosts and the waterhole over a distance of about 300 m in soft sand that was often hot in summer. Males did not accompany females that had offspring. Subordinate males were on the outskirts around the dominant males (e.g. No. 25 in Fig. 5). A subordinate male is characterized as one that makes a "kohok kohok" call when an adult male approaches, as was determined previously in an aviary (van Niekerk, 2009) and observed at Gunsbewys when a playback call was broadcast to subordinate males.

Territorial (dominant) males were characterized as (1) adults with fully grown red leg spurs, (2) males that invariably approached the playback calls, (3) males that approached females as they arrived at the waterholes, (4) males that started displaying in front of females when playback calls were broadcast and (5) males that were paired with females but ran up and down for 100–150 m in search of the source of the playback call. These males were invariably observed close to waterholes, which served as vantage points to detect incoming females or younger subordinate males that approached the waterholes. Two dominant males were invariably observed close to each other at both Wolwedraai and Gunsbewys, about 200 m apart, but often converged on the same female as she approached or passed through their home range. Sometimes (n = 3) females sat in trees calling and invariably both males approached and took turns in chasing her.

The mean maximum distance between two spurfowls within their dispersion areas as a sub-population at a waterhole was 419 m (SD = 82, n = 7, range 346–543). Throughout all four field surveys, only two pairs of Red-billed Spurfowl were observed further than 500 m away from open water. On 6 February 2011, at about 18:00 a male and female was observed between two waterholes, about 2.4 km from Wolwedraai and 1.8 km from Gunsbewys. On 7 February 2011, another pair was observed in the morning at about 08:00, 4.3 km from another waterhole in the reserve. Both observations were made on relatively cool days during a rainy period, suggesting that long distance movements take place during cool wet conditions. Both coveys were breeding pairs, as the males had bright red leg spurs and reacted vigorously to playback calls.

A few spurfowls were heard near Avondster at a waterhole in MNR in June 2010, but they only remained for a week as was the case the previous year (G. Botha, pers. comm.). Similarly, according to the game wardens (Table 1), small groups were occasionally observed at another waterhole 10 km northwest of Wolwedraai. While some groups appear to remain permanently around some waterholes, there is most certainly movement between sub-populations from time to time, as was also reported by landowners (Table 1).

According to the landowners Red-billed Spurfowl have been residents on a number of farms in the northwest corner of the North West Province of South Africa for the last 20–70 years (Table 1). Red-billed Spurfowl did not colonize this area from Botswana in the 1990s as reported by Hockey et al. (2005) and their distribution status and population sizes are not determined by long distance (30–100 km) and/or seasonal movements between the two countries. In fact, it is possible that Red-billed Spurfowl were present in the area prior to 1940, since most of the landowners interviewed, arrived and found the birds there which suggest that Red-billed Spurfowl did not colonize South Africa.

Red-billed Spurfowl are sparsely distributed and mainly occur in clusters near man-made waterholes that are filled with borehole water. An area of ~30 ha around waterholes forms the livelihood of Red-billed Spurfowl where mate selection, courting, breeding, feeding and drinking takes place. In Swainson's P. swainsoni and Cape P. capensis Spurfowl, similar sub-populations clustered around scratching patches (J.H. van Niekerk, 2004, personal observations) and in Red-throated Spurfowl (P. afer), a sub-population clustered around a daily feeding spot (van Niekerk et al., 2009). In all four species, two or three dominant males formed around the core area of the sub-population. These were the dominant males that clashed with each other, paired with the adult females in the sub-population and chased young males to the outskirts of their prime habitat.

The movement of Red-billed Spurfowl between waterholes over short distances of 2–5 km was probably encouraged by the sinking of more boreholes since the 1980s (and creation of 'veeposte' (game/livestock camps) around them). This made the birds more visible to farmers and their population probably increased (H. Beyleveld, pers. comm.). The absence of resident groups around four of the six waterholes surveyed in the MNR is surprising, since the two holes at Avondster are only 500 m apart. One of these holes is situated at a camp and the other at a house, both are occupied almost permanently by humans that ensure food scraps and open water and the number of antelope visiting these holes is similar to the numbers at waterholes where spurfowls are permanent residents, so a lack of food from droppings is unlikely. Predatory birds may be a factor, since the female-offspring coveys at Gunsbewys preferred to live in shrubland that offered concealment (Fig. 5).

The mean group size of 2.14–2.15 at the MNR (Table 2) is smaller than the mean group size of four Red-billed Spurfowl groups in the Waterberg Plateau Nature Reserve (WPNR) in Namibia and the mean groups size of five for Cape Spurfowl in Cape Town (J.H. van Niekerk, personal observations). A 12% sub-adult component in the MNR population is considered very low, compared to a sub-adult component of 30%–40% for other terrestrial gamebirds, such as Orange River, Crested (Dendroperdix sephaena) and the Coqui (Peliperdix coqui) Francolins and the Helmeted Guineafowl (van Niekerk, 2010, unpublished).

While females can produce relatively large broods of up to six chicks in this region (Table 1), chicks perish soon after hatching since arthropods are very limited in this dry region. Arthropods form an important part of the diet of chicks and in the case of the Red-billed Spurfowl a substantial volume of this could come from within the droppings of antelope in the MNR, or of cattle on the outlying farms (Fig. 2). Antelope and cattle gather daily around waterholes and veeposte, which make this a favorate habitat for the Red-billed Spurfowl.

Low rainfall that results in limited insects is probably the single most important factor limiting group sizes and breeding success of Red-billed Spurfowl in South Africa. Similarly, the availability of arthropods was also regarded as a major population-limiting factor for Helmeted Guineafowl populations in semi-arid habitats near Kimberley (Crowe, 1978). On the other hand, in the more mesic Krugersdorp Game Reserve, the replacement of pioneer plants on fallow vegetable gardens by more permanent grass monocultures caused a population decline of Swainson's Spurfowl due to diminished scratching patches for such underground food items as bulbs and grass roots (van Niekerk, 2011).

Finally, in South Africa species, such as Red-billed, Red-throated and Swainson's Spurfowl, often benefit from human modifications such as waterholes and grain cultivation but conversely the number of grass-living francolins such as the Grey-winged S. afra, the Red-winged S. levaillantii and the Orange River Francolins are often reduced by cultivation, grass burning and gazing (Crowe, 2009).

I thank Ann Jones for assisting during field research.

|

Crowe TM. 2009. Management of Southern African Gamebirds: Opportunities and Threats. In: Cederbaum CB, Faircloth BC, Terhune TM, Thompson JJ, Carroll JP (eds) Gamebirds 2006: Quail Vi and Perdix XII. Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, Athens, GA, USA, pp 11–15.

|

|

Crowe TM. 1978. Limitation of population in the helmeted guineafowl. S Afr J Wildl Res, 8: 117–126.

|

|

Hockey PAR, Dean WJR, Ryan PG. 2005. Roberts Birds of Southern Africa (7th ed). Trustees of the John Voelcker Bird Book Fund, Cape Town.

|

|

Komen J. 1987. Preliminary observations of the social pattern, behaviour and vocalizations of Hartlaub's francolin. S Afr J Wildl Res, 19: 82–86.

|

|

Little RM, Crowe TM. 2011. Gamebirds of Southern Africa. Struik Publishers, Cape Town.

|

|

Madge S, McGowan. 2002. Pheasants, Partridges and Grouse. Christopher Helm, London.

|

|

Milstein P le S, Wolff SW. 1987. The oversimplification of our 'francoilins'. S Afr J Wildl Res, Suppl. 1: 58–65.

|

|

Mucina L, Rutherford MC. 2006. The Vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. Strelizia 19. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria.

|

|

Stuart C, Stuart T. 2000. A field Guide to the tracks and signs of Southern and East African Wildlife. Struik Publishers, Cape Town.

|

| Farm name/locality | Respondent/warden | Group size | Earliest date observed | Comments |

| Gemsdraai | R. Boshof | Two groups totalling about 12 spurfowl | Since farmer's arrival on farm 4 years ago. | Occur around farm house. Permanent residents. |

| Toranto | H. Burger | 6–10 spurfowl in at least two groups | Since farmer's arrival 7 years ago. | Occur around farm house. Permanent residents. |

| Batley | W. Jones | 3–4 spurfowl | Observed for last 25 years since his arrival. | Foraged in small maize fields. Permanent residents. |

| Vostershoop shop | J. Strydom | 5–6 spurfowl | Observed daily at shop during 2008–2009 but disappeared since. | Fed on grains given to chickens daily. |

| Watersend | J. Holtshauzen | 6–7 spurfowl | Since farmer's arrival 21 years ago. | Covey with chicks around house in January 2011. Permanent residents. |

| De Rust | W. Harvey | Groups of 2–3 around the house | Since first noticed about 30 years ago. | Permanent residents |

| Arizona | J. Olyn | Two groups of about 3 each | Observed since his arrival in 1999 around veeposte. | Permanent resident. Hens produce up to 6 and more chicks. |

| Gunsbewys (MNR) | G. Botha | Sub-population of 6 spurfowl | Since arrival in reserve 9 years ago. | Permanent residents |

| Freddie McDonald's farm | Employee | Seen three on 16 December 2009. | ― | Seen during midday coming to drink water. |

| Vostershoop | N. Voster | Often seen at veeposte where they drink water. Occur in small groups. | Observed since his arrival in 1940. Permanent in area but move locally. | Vostershoop named after his father in 1940. Female produced 6 chicks. |

| Montreal | H. Beyleveld | Small groups of 2–3 spurfowl | Only observed since 1985. | Locally nomadic |

| Number of farms around Vostershoop | H. Mokaadi | Small groups | Since arrival at Vostershoop in 1999. | Observed spurfowl as child in Morokweng during 1960–1966. Permanent residents. |

| Wolwedraai Camp (MNR) | J. Diseko (game warden) | Sub-population of about 10 | Since his arrival 35 years ago. | Spurfowls forage around campsite. Permanent residents. |

| Aurora | C. Ras | No spurfowls observed around house. | Arrived on farm 15 months ago. | ― |

| Wolwedraai | Gunsbewys | |

| Mean sub-population size | 4.3 (n = 3, SD = 1.52, range = 3–6) | 4.25 (n = 4, SD = 0.95, range = 3–5) |

| Number of coveys observed per hour | 0.33/hour | 0.37/hour |

| Mean group size | 2.14 (n = 14, SD = 0.86, range = 1–4) | 2.15 (n = 20, SD = 0.95 range = 1–5) |

| Dispersion areas of sub-populations (polygon drawn around all sightings including all site visits) | 24 ha | 34 ha |

| Density (dispersion area/mean sub-population size) | 0.179 spurfowl/ha | 0.125 spurfowl/ha |