| Citation: | Farzana PERVEEN, Hafeez Ullah KHAN. 2010: Pressure from hunting on crane species in southern districts of northern Pakistan. Avian Research, 1(4): 244-250. DOI: 10.5122/cbirds.2010.0021 |

This study was carried out to assess the biological status of two crane species, the Common Crane (Grus grus L.) and the Demoiselle Crane (Anthropoides virgo L.), with respect to the hunting pressure in two southern districts of northern Pakistan, Bannu and Lakki. Field surveys, interviews and questionnaires were the major tools for data collection. We visited 165 hunting camps in the fall of 2008 and 85 in the spring of 2009 in the two districts. Of the hunters, most possessed wildlife permits for hunting and most people hunted for recreation. According to our survey, the population of two crane species is declining due to overhunting, destruction of natural habitats, anthropogenic activities and geographical factors. Suggestions for protection of the cranes are proposed.

Three crane species, the Common Crane (Grus grus L.), the Demoiselle Crane (Anthropoides virgo L.) and the Siberian Crane (Grus leucogeranus Pallas), migrate through Pakistan to wintering grounds in the subcontinent (Johnsgard, 1983). The Common and Demoiselle Cranes breed in Russia, then migrate to Pakistan. They migrate south in the autumn via routes along Pakistan's northern and western borders. The Siberian Cranes are nearly extinct in this area with only a few birds passing through Pakistan along unknown routes to their sole wintering grounds in Keoladeo National Park, Bharatpur, India (UNEP/CMS, 1995; BirdLife International, 2001). In northern Pakistan, cranes fly back over the Indus, Kurram, Gambela, Kashew and Gomal Zam rivers. In Baluchistan, cranes fly back over the Zhob River through Chaghi and Noshki (Farooq et al., 1993; Khan, 2004). Six main populations of the Demoiselle Crane are recognized here. The three eastern populations in East Asia, Kazakhstan/Central Asia and Kalmykia are abundant, ranging from 100 to 1000. The Black Sea population consists of approximately 500 birds. A disjunctive resident population in the Atlas Plateau of north Africa is believed to include no more than 50 individuals. A small breeding population exists in Turkey (Smirenski, 2000; Meine and Archibald, 2004). This species breeds in Eurasia and the steppes from the Black Sea to northeastern China. The main wintering grounds are India, Sudan and other portions of East Africa to Chad (International Crane Foundation, 2001; Meine and Archibald, 2004). Demoiselle Cranes are primarily grassland birds, but are usually found within a few hundred meters of rivers and other natural wetlands. If water is available, they will inhabit even semi-deserts and true deserts. Their winter habitats in East-Central Africa include acacia savannahs, grasslands and riparian areas. In India, they feed in agricultural fields and roost on sandbars and mudflats surrounded by water (Ahmad and Khurshid, 1991; Meine and Archibald, 2004). Common and Demoiselle Cranes migrate south in search of food and favorable environments and north for nesting and breeding. During this migration through Pakistan, they come across heavy odds of physical barriers, inclement weather, predators, food scarcity and hunting pressures (Khan, 1990; Shafiq, 1998).

During the migration seasons intensive hunting of cranes is carried out throughout northern Pakistan especially in the southern districts, where some cranes are killed while a reasonable number is caught alive. Those are kept and reared with great interest and care. Every effort is made for the safety and breeding of these cranes, but due to the lack of proper organized and scientific techniques, the desired results are seldom obtained (Shafiq, 1998; DeCarlo, 2004). The objectives of our research were to determine the distribution, population status and the pressure from hunting on cranes in the southern districts of northern Pakistan, identify possible threats to their population and suggest recommendations for their conservation.

The research was conducted in Bannu and Lakki, the southern districts of northern Pakistan and FATA (Federally Administered Tribal Areas) of Kurram and NWA (North Waziristan Agencies), located in one of the most beautiful valleys, the Kurram Valley. This valley is reached from the Darra Tang, northwest to the confluence of the Kurram and Indus rivers in Lakki. Part of the watershed of the Kurram Valley extends beyond the international border into Afghanistan. The watershed is defined by the Kurram River and its tributaries which include the Kashu and Gambilla rivers, and consists of arid, semi-arid plains and foothills, ranging from 300–4761 m in elevation.The river runs for about 25 km to the Tangi and Kethu rivers, and then enters Bannu and Lakki. Finally, the Kurram River flows into the Indus River at Dara Tang near Isa Khel (Robert and Landfried, 1987; Khan, 2004).

Two crane species, the Common and Demoiselle Crane migrate through Pakistan. To capture wild cranes, hunters of the Kurram Valley use captive cranes as decoy to attract wild cranes by their presence and calls. The hunters train their captive cranes in such a way that they call in response to a signal from the owners (Farooq, 1992; Ahmad and Jan, 1995).

The survey was conducted during the fall of 2008 and the 2009 spring in the Kurram Valley of northern Pakistan, the most important hunting areas of cranes, which include Bannu, Lakki and FATA of Kurram and NWA. The data were collected in the fall of 2008, from September 1 to November 30 and in the spring of 2009, starting on February 25 and lasting to April 15. Field surveys, interviews and questionnaires were the tools for data collection.

From the data collected, we calculated means and standard deviations using the following equations:

|

|

where X is the total number of cranes per hunting site (captured or killed), n the number of hunting sites and M the mean number of cranes;

|

|

where SD is the standard deviation.

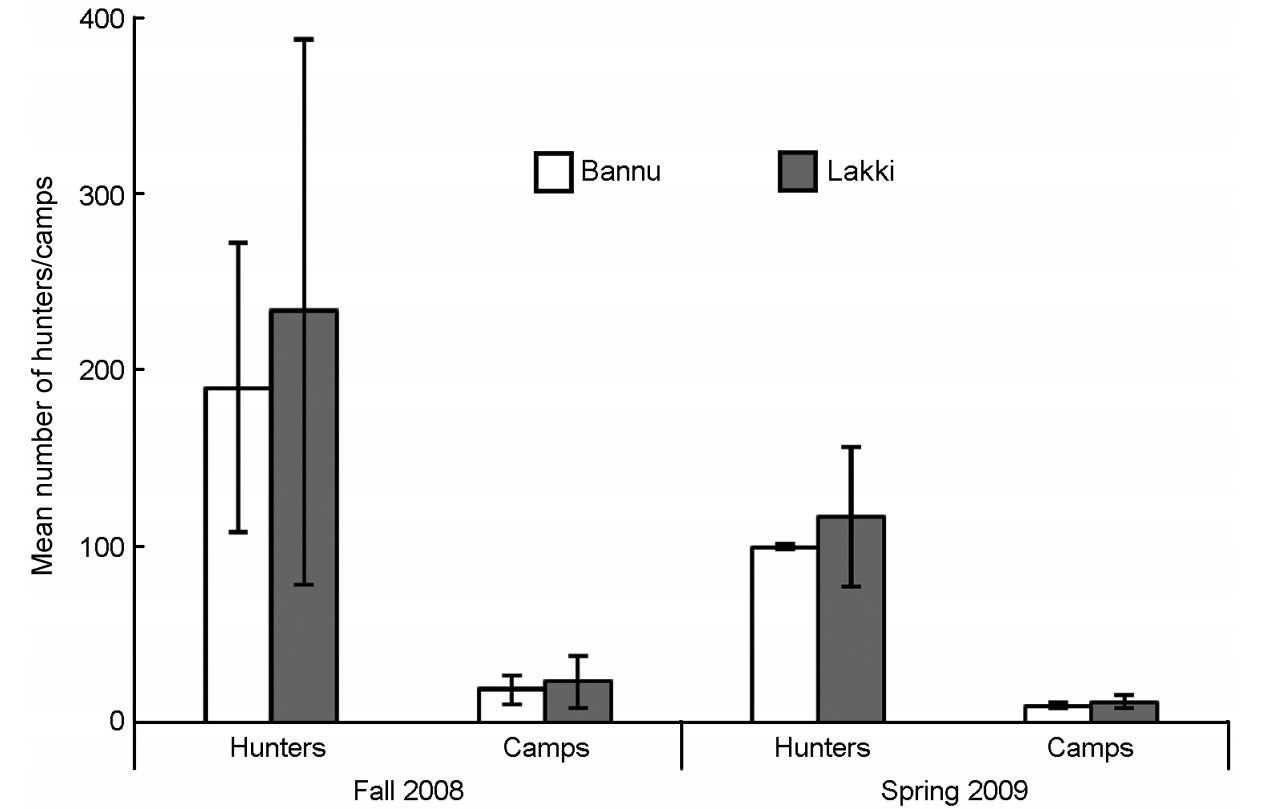

During the fall of 2008, a total of 165 hunting camps were established, 95 in Bannu (25 at the Baran Dam, 30 at the Kurram River, 20 at Kashu, 13 at Kethu and 7 at the Dowa hunting sites) and 70 in Lakki (45 at the Gambilla River, 14 at Lunder and 11 at the Chall hunting sites). An average of 19 ± 8 camps with 190 ± 82 hunters were at each hunting sites in Bannu and 23 ± 15 camps with 233 ± 154 hunters at each hunting site in Lakki (Fig. 1). During the spring of 2009, a total of 85 camps were established, 50 in Bannu (13 at the Baran Dam, 11 at the Kurram River, 10 at Kashu, 9 at Kethu and 7 at Dowa) and 35 in Lakki (17 at the Gambilla River, 10 at Lunder and 8 at Chall). An average of 10 ± 2 camps with 100 ± 2 hunters were in Bannu and 12 ± 4 camps with 117 ±39 hunters in Lakki (Fig. 1).

During the fall of 2008, a total of 665 Demoiselle and 190 Common Cranes were captured in Bannu. The maximum and minimum number of Demoiselle and Common Cranes were captured in the Baran Dam and Dowa, compared to other hunting sites in Bannu. During the fall of 2008, 190 Demoiselle and 45 Common Cranes were killed in Bannu. The maximum and minimum number of Demoiselle and Common Cranes were killed in the Baran Dam and Dowa compared to other hunting sites in Bannu (Table 1). During the spring of 2009, a total 250 Demoiselle and 100 Common Cranes were captured in Bannu. The most and fewest number of Demoiselle and Common Cranes were captured in the Baran Dam and Dowa compared to other hunting sites in Bannu. During the spring of 2009, a total 99 Demoiselle cranes were killed in Bannu, with most at the Baran Dam and the smallest number in Dowa. However, no Common Crane was killed in any of the Bannu hunting areas (Table 1). The average number of captured cranes per camp in the fall of 2008 was nine, of which seven were Demoiselle and two were Common Cranes, while in the spring of 2009 seven were captured, of which five were Demoiselle and two Common Cranes.

| Hunting season | Captured /killed | Species of crane | Number of cranes | |||||

| Total in Bannu | Baran Dam | Kurram River | Kashu | Kethu | Dowa | |||

| Fall 2008 | Captured | Demoiselle | 665 | 250 | 190 | 105 | 85 | 35 |

| Common | 190 | 70 | 45 | 36 | 24 | 15 | ||

| Killed | Demoiselle | 190 | 90 | 50 | 25 | 15 | 10 | |

| Common | 45 | 23 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Spring 2009 | Captured | Demoiselle | 250 | 95 | 75 | 45 | 20 | 15 |

| Common | 100 | 50 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 5 | ||

| Killed | Demoiselle | 99 | 32 | 45 | 10 | 7 | 5 | |

| Common | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

During the fall of 2008, a total of 490 Demoiselle and 140 Common Cranes were captured in Lakki. In the Gambilla River, the maximum number of Demoiselle and Common cranes were captured and the smallest number in Chall, compared to other hunting sites in Lakki. During the fall of 2008, 150 Demoiselle and only 5 Common Cranes were killed in Lakki. Also in the Gambilla River, the largest number of Demoiselle Cranes were killed and in Chall the fewest, compared to other hunting sites in Lakki (Table 2). The average number of captured cranes per camp in the fall of 2008 was nine, of which seven were Demoiselle and two Common Cranes. In the spring of 2009, a total 175 Demoiselle and 70 Common Cranes were captured in Lakki. In the Gambilla River, the largest number of Demoiselle Cranes were captured, compared to other hunting sites but no Common Crane in Chall. In the spring of 2009, 70 Demoiselle Cranes were killed in Lakki, while no Common Crane was killed in any of the Lakki hunting sites. In the Gambilla River, the maximum number of Demoiselle Cranes were killed; however, no Common Crane was killed in Chall, neither in the fall of 2008 and nor in the spring of 2009 (Table 2). The average number of captured cranes per camp in the 2009 spring was seven, five of them Demoiselle and two Common Cranes.

| Hunting season | Captured /killed | Species of crane | Number of cranes | |||

| Total in Lakki | Gambilla River | Lunder | Chall | |||

| Fall 2008 | Captured | Demoiselle | 490 | 350 | 85 | 55 |

| Common | 140 | 90 | 30 | 20 | ||

| Killed | Demoiselle | 150 | 115 | 20 | 15 | |

| Common | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Spring 2009 | Captured | Demoiselle | 175 | 105 | 60 | 10 |

| Common | 70 | 64 | 6 | 0 | ||

| Killed | Demoiselle | 70 | 32 | 23 | 15 | |

| Common | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

During the fall of 2008, 175 Demoiselle and Common Cranes were captured in Bannu, 50 more compared with Lakki. Moreover, during the spring of 2009, 75 Demoiselle and Common Cranes were captured in Bannu, 30 more than in Lakki. Furthermore, during the 2008 fall, 50 Demoiselle and Common Cranes were killed in Bannu, 40 more than in Lakki (Tables 1 and 2).

During our various interviews with hunters during the present survey, we recorded average numbers of cranes captured and killed during the last five-years (2004–2008). Of the Demoiselle Cranes 900 ± 460 were captured and 245 ± 209 killed, compared with the Common Cranes of which 245 ± 209 were captured and 150 ± 66 killed in Bannu. However, in Lakki, the average number of the Demoiselle Cranes captured was 900 ± 568 and 375 ± 121 were killed, compared with the Common Cranes of which 225 ±153 were captured and 150 ± 60 killed. It appeared that a total of 120 camps were established in both districts during the last five-years.

During our survey, 950 hunters were interviewed in Bannu and 700 in Lakki to determine the purpose of hunting. It was found that most people hunted for recreation, only few people hunted both for recreation and earning. However, nobody hunted for only earning. Among the hunters 92% from Bannu and 83% from Lakki were in possession of wildlife permits for hunting. All of the hunters (100%) were in favor of the proposition that no one should be allowed to shoot cranes. The population of two crane species is expected to decline due to overhunting, destruction of their natural habitats, anthropogenic activities and varying geographical factors.

Exact routes used by cranes for entering and leaving Pakistan are not clearly known. During our recent research, it was noted from various hunters that during the fall migratory cranes enter through rout via Zhob from Afghanistan. From Zhob they enter Bannu and Lakki, while in the spring they pass through Lakki and Bannu. From here they enter Afghanistan through Parachinar. The majority of cranes are seen on the Indus, Kurram, Kashu, Zhob and Gambilla rivers (Farooq et al., 1993). It was recently discovered that a popular entry route of cranes lies in the district Chagai, Baluchistan.

In 1966, 5000 cranes were reported to have either been trapped alive or shot. Interviews with 100 hunters in D.I. Khan and Bannu areas indicated that they were able to kill or catch 10–15% of the migrating cranes. According to game staff and local villagers in the Chagai district, about 20000 cranes enter each year through Zaro-Anam Bostan in Baluchistan in the fall and move eastwards. In the spring of 1989, about 700 cranes used this route. From this, it was concluded that the total number of cranes using Pakistan for migration could be around 50000 (Farooq et al., 1993). According to our survey, in the fall of 2008 and the spring of 2009, about 7000 cranes passed through Bannu and Lakki, which means that it is still a favorite route for the migration of cranes.

According to Kanai (2000) the hunters of the Kurram Valley trapped 4000 cranes and 100 were killed during the 1986 fall and the spring of 1987. About 3000 to 5000 cranes were captured in 1995 (Ahmad and Jan, 1995). According to our research, a total of 885 Demoiselle and 215 Common Cranes were reported to be killed during the fall of 2008 and the spring of 2009 (Table 2).

During the 2008 fall and 2009 spring, a total of 2080 cranes were captured and 559 were killed. Of the 2080 captured cranes, 1580 were Demoiselle Cranes and 500 were Common Cranes while 509 Demoiselle and 50 Common Cranes were killed. The total captured per camp was about eight cranes and the number killed per camp about two (Tables 1 and 2). Hunting of Common and Demoiselle Cranes is incidental and takes place mostly on rainy days or in bad weather (Khan, 1998).

According to Khan (2004), 1502 licenses had been issued in Bannu and Lakki by the D.I. Khan Wildlife Department. In Pakistan, the total number of registered cranes was 12222, up from the year earlier. During our research, in Bannu and Lakki, out of a total of 1650 hunters in 165 camps, 1444 had wildlife permits. Recently, hunters from Bannu have started to use politicians to obtain crane-hunting permits in Zhob. The ban on outside hunters could easily save about 500 cranes each year and may guarantee the safe journey of wild cranes (Farooq et al., 1993).

From our investigation, we conclude that the population of migratory cranes is expected to decline in southern districts of northern Pakistan due to overhunting, destruction of natural habitats and high levels of anthropogenic activities. There are no effective protection measures for these cranes.

However, for their protection, the Government of Northern Pakistan took the following steps: 1) the endangered Siberian Crane, which is suspected to travel through northern Pakistan during migration, has been declared "protected" and hunting, killing and capturing of the bird have been completely banned; 2) hunting, killing or capture of cranes by means of fire arms or any other device has been prohibited; 3) Dealing in crane hunting, trade or business is now illegal; 4) hunting is allowed only in the spring and fall; the fee for spring hunting per camp is Rs. 1000 and Rs. 500 for the fall; 5) the fee for possessing a license is Rs. 50 per crane to discourage possession of cranes as pets; 6) a fee of Rs. 500 to prohibit the export of cranes from the province in the country is charged and Rs. 2000 per crane for outside the country; 7) to discourage crane hunting by the young people, hunting licenses are issued only to persons over 18 years of age.

In order to protect and restore the endangered crane population and its habitats, the following specific suggestions for protection at the local level must be taken: 1) the rules regarding hunting of cranes in northern Pakistan need to be revised and oriented more towards protection; 2) improve the techniques of breeding populations; 3) study the factors behind poor reproduction and rates of recruitment in crane populations with an effective reintroduction of cranes; 4) expand cooperation and collaboration among ornithologists, conservationists and those working in the breeding range of crane populations; 5) take eco-tourism measures and extend public education programs involving farmers; 6) habitats should be protected from agro-industrial chemical pollution.

We thank Prof. Dr. Muhammad Arshad (Deceased), Mr. Khan Malook (DFO, Wildlife Department, Bannu), Mr. Abdul Haleem (DFO, Wildlife Department, D.I. Khan) and Dr. Lutf Ullah Kakakhel (Vice Chancellor) for providing all possible information and cooperation during our research. We are grateful to many volunteers and hunters who contributed to our survey.

|

Ahmad A, Jan A. 1995. Cranes in Pakistan. Crane research and protection in Europe, pp 337–352.

|

|

Ahmad A, Khurshid N. 1991. Observation of migration and migratory routes of cranes through Balochistan. Nature, 13: 8–11.

|

|

BirdLife International. 2001. Threatened birds of Asia. BirdLife Intern, 1: 45–77.

|

|

Farooq M, Ahmad A, Ghalib SA. 1993. The cranes of Pakistan. World Wide Fund for Nature, Pakistan, pp 1–54.

|

|

Farooq M. 1992. Crane migration through Dera Ismail Khan (N-WFP): Conservation problems and prospects. Dissertation, Pakistan Forest Institute, Peshawar, Pakistan, pp 1–135.

|

|

Johnsgard A. 1983. Cranes of the World. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, pp 1–95.

|

|

Kanai L. 2000. Migration of demoiselle cranes in Asia based on satellite tracking and fieldwork. Global Environ Res, 4: 143–153.

|

|

Khan A. 1998. Cranes of N-WFP. Dissertation. Pakistan Forest Institute, Peshawar, pp 1–45.

|

|

Khan A. 2004. Habitat status and hunting pressure on migratory cranes in Pakistan and assessment of Lake Ab-i-Estada in Afghanistan with propose conservation plans for selected wetlands. Dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA, pp 1–160.

|

|

Khan AA. 1990. The wildlife of Sindh arid zone-variety, threats and potential. Report prepared for the FMS/AG RODEV. SAZDA. IUCN, the World Conservation Union, Pakistan, pp 1–16.

|

|

Robert TJ, Landfried SE. 1987. Hunting pressure on cranes migrating through Pakistan. In: Archibald GW, Pasquier RF (eds) Proceeding of the International Crane Foundation, Baraboo. University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA, pp 139–145.

|

|

Shafiq MM. 1998. Cranes migration through NWFP: conservation problems and Prospects. Oriental Bird Club, 1–18.

|

|

UNEP/CMS. 1995. Memorandum of Understanding Concerning Conservation Measures for the Siberian Crane: Report of the First Meeting of Range States. CMS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany, pp 1–113.

|

| 1. | Meng Yue Wu, Frank E. Rheindt. Continent-wide vocal leapfrog pattern in collared scops owls obfuscates species boundaries. Avian Research, 2023. DOI:10.1016/j.avrs.2023.100141 |

| 2. | Nyanasengeran Movin, Tatjana Gamova, Sergei G. Surmach, et al. Using bioacoustic tools to clarify species delimitation within the Blakiston's Fish Owl (Bubo blakistoni) complex. Avian Research, 2022, 13: 100021. DOI:10.1016/j.avrs.2022.100021 |

| 3. | Yong Chee Keita Sin, James A Eaton, Robert O Hutchinson, et al. Re-assessing species limits in a morphologically cryptic Australasian kingfisher lineage (Coraciiformes: Halcyonidae) using bioacoustic data. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2022, 136(4): 489. DOI:10.1093/biolinnean/blac047 |

| 4. | George Sangster, Kim Manzon Cancino, Robert O. Hutchinson. Taxonomic revision of the Savanna Nightjar (Caprimulgus affinis) complex based on vocalizations reveals three species. Avian Research, 2021, 12(1) DOI:10.1186/s40657-021-00288-z |

| 5. | Chyi Yin Gwee, Qiao Le Lee, Simon P. Mahood, et al. The interplay of colour and bioacoustic traits in the differentiation of a Southeast Asian songbird complex. Molecular Ecology, 2021, 30(1): 297. DOI:10.1111/mec.15718 |

| 6. | AMIT HEGDE, K.P. DINESH, GIRISH KADADEVARU. Phenotypic divergence in large sized cricket frog species that crossed the geographical barriers within peninsular India. Zootaxa, 2020, 4838(2) DOI:10.11646/zootaxa.4838.2.3 |

| 7. | Jessie F Salter, Carl H Oliveros, Peter A Hosner, et al. Extensive paraphyly in the typical owl family (Strigidae). The Auk, 2020, 137(1) DOI:10.1093/auk/ukz070 |

| 8. | Frank E. Rheindt, Dewi M. Prawiradilaga, Hidayat Ashari, et al. A lost world in Wallacea: Description of a montane archipelagic avifauna. Science, 2020, 367(6474): 167. DOI:10.1126/science.aax2146 |

| Hunting season | Captured /killed | Species of crane | Number of cranes | |||||

| Total in Bannu | Baran Dam | Kurram River | Kashu | Kethu | Dowa | |||

| Fall 2008 | Captured | Demoiselle | 665 | 250 | 190 | 105 | 85 | 35 |

| Common | 190 | 70 | 45 | 36 | 24 | 15 | ||

| Killed | Demoiselle | 190 | 90 | 50 | 25 | 15 | 10 | |

| Common | 45 | 23 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Spring 2009 | Captured | Demoiselle | 250 | 95 | 75 | 45 | 20 | 15 |

| Common | 100 | 50 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 5 | ||

| Killed | Demoiselle | 99 | 32 | 45 | 10 | 7 | 5 | |

| Common | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Hunting season | Captured /killed | Species of crane | Number of cranes | |||

| Total in Lakki | Gambilla River | Lunder | Chall | |||

| Fall 2008 | Captured | Demoiselle | 490 | 350 | 85 | 55 |

| Common | 140 | 90 | 30 | 20 | ||

| Killed | Demoiselle | 150 | 115 | 20 | 15 | |

| Common | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Spring 2009 | Captured | Demoiselle | 175 | 105 | 60 | 10 |

| Common | 70 | 64 | 6 | 0 | ||

| Killed | Demoiselle | 70 | 32 | 23 | 15 | |

| Common | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||